For COVID-19 frequently asked inpatient questions, click here

For COVID-19 frequently asked outpatient questions, click here

Editor-In-Chief: C. Michael Gibson, M.S., M.D. [1]; Associate Editor(s)-in-Chief: Mitra Chitsazan, M.D.[2]Mandana Chitsazan, M.D. [3]

Synonyms and keywords: Novel coronavirus, COVID-19, Wuhan coronavirus, coronavirus disease-19, coronavirus disease 2019, SARS-CoV-2, 2019-nCoV, 2019 novel coronavirus, heart failure, acute heart failure, de Novo acute heart failure, chronic heart failure, acute decompensated heart failure, HFrEF, HFpEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction

Overview[edit | edit source]

Both de novo acute heart failure and acute decompensation of chronic heart failure can occur in patients with COVID-19. Patients with chronic heart failure may be at higher risk of developing severe COVID-19 infection due to advanced age and the presence of multiple comorbidities.

Historical perspective[edit | edit source]

- In late December 2019, the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, originated in Wuhan, China. [1]

- The World Health Organization(WHO) declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern On January 30, 2020, [2] and a pandemic on March 12, 2020. [3]

- On March 27, 2020, Inciardi et al. reported the first case of acute myopericarditis complicated by heart failure in an otherwise healthy 53-year-old woman one week after the onset of symptoms of COVID-19. [4]

Classification[edit | edit source]

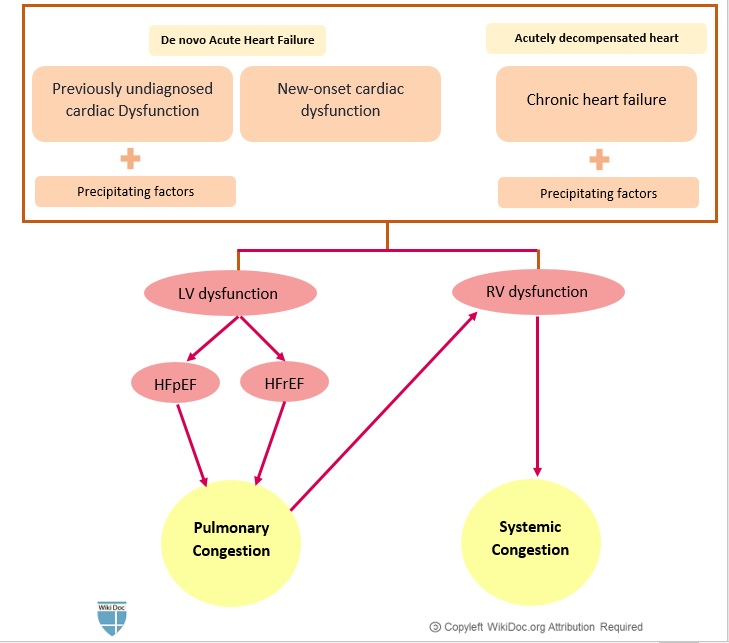

- Heart Failure (HF) during COVID-19 infection may be classified similarly to heart failure from other causes.

- In general, heart failure can be classified based on:

- The pathophysiology of heart failure:

- The duration of symptoms:

- Acute HF (AHF) vs chronic HF (CHF)

- The underlying physiology based on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF):

- The severity of heart failure (i.e., the New York Heart Association Class I-IV)

- The stage of congestive heart failure (i.e., AHA Class A, B, C, D)

- Acute heart failure has two forms:

- Newly-arisen (“de novo”) acute heart failure

- Acutely decompensated chronic heart failure (ADCHF)

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

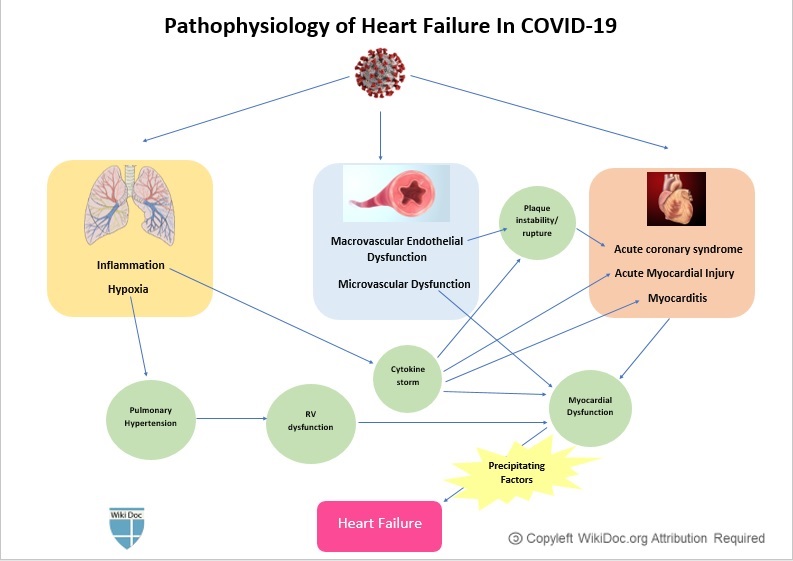

- Presumed pathophysiologic mechanisms for the development of new or decompensated heart failure in patients with COVID-19 include:[5] [6] [7] [8] [9]

- Acute exacerbation of chronic heart failure caused by precipitating factors

- Acute myocardial injury (which in turn can be caused by several mechanisms)

- Stress cardiomyopathy (i.e., Takotsubo cardiomyopathy) [10] [11]

- Impaired myocardial relaxation resulting in diastolic dysfunction [i.e., Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) ]

- Right-sided heart failure, secondary to pulmonary hypertension caused by hypoxia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

| Common Precipitating factors in COVID-19 patients |

| Cardiac |

|

| Pressure overload |

|

| Volume overload |

|

|

| Pulmonary |

| Increased systemic metabolic demand |

| Iatrogenic |

|

|

| Others |

|

|

Causes[edit | edit source]

Acute heart failure in COVID-19 patients may be caused by: [10] [11]

- Acute myocardial injury

- Acute coronary syndromes

- Myocarditis

- Hypertensive crisis

- Arrhythmias: Tachycardia or severe bradycardia

- Stress-induced cardiomyopathy (Takotsubo cardiomyopathy)

- Circulatory failure:

- Iatrogenic

Differentiating COVID-19 associated heart failure from other Diseases[edit | edit source]

- For further information about the differential diagnosis, click here.

Epidemiology and Demographics[edit | edit source]

- Data on incidence on acute heart failure in COVID-19 patients is limited.

- In one study, acute heart failure was seen in 4.1% of patients with acute cardiac injury. [12]

- In a retrospective study on 191 COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China, the incidence of heart failure was 23% (52% in non-survivors vs 12% in survivors). [13]

Age[edit | edit source]

- Heart failure commonly affects older patients with COVID-19.

Gender[edit | edit source]

- There is no data on gender predilection to heart failure in COVID-19.

Race[edit | edit source]

- There is no data on racial predilection to heart failure COVID-19.

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

- The most common risk factors in the development of acute heart failure in COVID-19 patients are:

- Older age

- Pre-existing congestive heart failure

- Well-established risk factors of heart failure, including:

To read more on the risk factors of congestive heart failure, click here.

Screening[edit | edit source]

- There is insufficient evidence to recommend routine screening for heart failure in COVID-19 patients.

- Routine measurement of natriuretic peptides and/or cardiac troponins has not been recommended in the absence of a high index of suspicion for heart failure on the clinical grounds.

Natural History, Complications, and Prognosis[edit | edit source]

- COVID-19 patients with chronic heart failure are more likely to develop severe forms of the disease.

- COVID-19 patients who develop acute heart failure (either de novo acute heart failure or acute decompensated heart failure) generally have worse outcomes.

- Acute heart failure in COVID-19 may progress to cardiogenic shock.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

History and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

- The most common symptoms of acute heart failure in COVID-19 patients are:

- New or worsening dyspnea: may overlap with dyspnea caused by concomitant respiratory involvement and acute respiratory distress syndrome due to COVID-19

- Orthopnea

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

- Peripheral edema

- Fatigue

- Palpitations

- Other common symptoms include:

- Confusion and altered mental status

- Cool extremities

- Cyanosis

- Dizziness

- Syncope

- Hemoptysis

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

- Physical examination of patients with acute heart failure is usually remarkable for:

- Tachycardia

- Crackles on lung auscultation

- Distended jugular veins

- Lower extremity edema and/or ascites

- ventricular filling gallop (S3) and/or atrial gallop (S4) on cardiac auscultation

Laboratory Findings[edit | edit source]

- Cardiac Troponins: [14]

- Elevated cardiac troponin levels suggest the presence of myocardial cell injury or death.

- Cardiac troponin levels may increase in patients with chronic or acute decompensated heart failure.

- Natriuretic Peptides: [15] [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22]

- Natriuretic peptides (BNP/NT-proBNP) are released from the heart in response to increased myocardial stress and are quantitative markers of increased intracardiac filling pressure.

- Elevated BNP and NT-proBNP are of both diagnostic and prognostic significance in patients with heart failure.

- Increased BNP or NT-proBNP levels have been demonstrated in COVID-19 patients.

- Increased NT-proBNP level was associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with severe COVID-19.

- However, increased natriuretic peptide levels are frequently seen among patients with severe inflammatory or respiratory diseases.

- Therefore, routine measurement of BNP/NT-proBNP has not been recommended in COVID-19 patients, unless there is a high suspicion of heart failure based on clinical grounds.

Electrocardiogram[edit | edit source]

- There is no specific electrocardiographic finding for acute heart failure in COVID-19 patients.

- The ECG may help in identifying preexisting cardiac abnormalities and precipitating factors, such as ischemia, myocarditis, and arrhythmias.

- These ECG findings may include:

- Low QRS Voltage

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- Left atrial enlargement

- Left bundle branch block

- Poor R progression

- Nonspecific ST-T changes

X-ray[edit | edit source]

- A Chest x-ray may be helpful in the diagnosis of heart failure. Findings on chest X-ray suggestive of heart failure include:

- Cardiomegaly

- Pulmonary congestion

- Increased pulmonary vascular markings.

- However, signs of pulmonary edema may be obscured by underlying respiratory involvement and acute respiratory distress syndrome due to COVID-19.

Echocardiography or Ultrasound[edit | edit source]

- A complete standard transthoracicechocardiography (TTE) has not been recommended in COVID-19 patients considering the limited personal protective equipment (PPE) and the risk of exposure of additional health care personnel.[23]

- To deal with limited resources (both personal protective equipment and personnel) and reducing the exposure time of personnel, a focused TTE to find gross abnormalities in cardiac structure/function seems satisfactory.

- In addition, bedside options, which may be performed by the trained personnel who might already be in the room with these patients, might also be considered. These include:

- Cardiac ultrasound can help in assessing the following parameters:

- Left ventricular systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction, LVEF) to distinguish systolic dysfunction with a reduced ejection fraction (LVEF<40%) from diastolic dysfunction with a preserved ejection fraction (LVEF>40%)

- Left ventricular diastolic function

- Left ventricular structural abnormalities, including left ventricular size and left ventricular wall thickness

- Left atrial size

- Right ventricular size and function

- Detection and quantification of valvular abnormalities

- Measurement of systolic pulmonary artery pressure

- Detection and quantification of pericardial effusion

- Detection of regional wall motion abnormalities/reduced strain that would suggest underlying ischemia.

CT scan[edit | edit source]

- A Chest CT scan may be helpful in the diagnosis of pulmonary edema in patients with heart failure.

- Findings suggestive of pulmonary edema include:

- Interstitial Edema:

- Gound-glass opacification

- Bronchovascular bundle thickening caused by increased vascular diameter and/or peribronchovascular thickening

- Interlobular septal thickening

- Alveolar edema:

- Airspace consolidation (in addition to findings of interstitial edema).

- Interstitial Edema:

- In patients with cardiogenic pulmonary edema, caused by increased pulmonary vasculature hydrostatic pressure, bilateral pleural effusions are also frequently seen.

CMR[edit | edit source]

- Due to the risk of contamination of equipment and staff, performing Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) should be limited to clinically urgent cases.

- Cardiac magnetic resonance may be helpful in patients suspicious of acute myocarditis, in particular when elevated cardiac biomarkers, ventricular dysfunction and/or severe arrhythmias cannot be explained by other diagnostics and imaging studies.

- To read more on the role of CMR in the diagnosis of myocarditis, click here.

Other Imaging Findings[edit | edit source]

- To view other imaging findings on COVID-19, click here.

Other Diagnostic Studies[edit | edit source]

- To view other diagnostic studies for COVID-19, click here.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Medical Therapy[edit | edit source]

- Acute heart failure in the setting of COVID-19 is generally treated similarly to acute heart failure in other settings. These may include:

- Fluid restriction

- Diuretic therapy

- Vasopressors and/or inotropes

- Beta-blockers should not be initiated during the acute stage due to their negative inotropic effects.[24]

- Patients with chronic heart failure are recommended to continue their previous guideline-directed medical therapy, including beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors or Angiotensin II receptor blockers, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. [25]

Interventional therapy[edit | edit source]

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be helpful in patients with cardiogenic shock unresponsive to medical therapy.

Surgery[edit | edit source]

- The mainstay of treatment for acute heart failure is medical therapy.

- Ventricular assisted devices are usually reserved for patients with cardiogenic shock.

Primary Prevention[edit | edit source]

- There are no established measures for the primary prevention of heart failure in patients with COVID-19.

Secondary Prevention[edit | edit source]

- During fluid management in heart failure patients, attempts would be done to prevent both volume overload and circulatory failure.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) should be used with caution in patients with acute heart failure due to their effect on fluid and sodium retention.[26]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "WHO | Pneumonia of unknown cause – China".

- ↑ "WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020".

- ↑ Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D, Cani DS, Cerini M, Farina D, Gavazzi E, Maroldi R, Adamo M, Ammirati E, Sinagra G, Lombardi CM, Metra M (March 2020). "Cardiac Involvement in a Patient With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". JAMA Cardiol. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. PMID 32219357 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Inciardi RM, Lupi L, Zaccone G, Italia L, Raffo M, Tomasoni D; et al. (2020). "Cardiac Involvement in a Patient With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". JAMA Cardiol. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. PMID 32219357 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Mehra MR, Ruschitzka F (2020). "COVID-19 Illness and Heart Failure: A Missing Link?". JACC Heart Fail. 8 (6): 512–514. doi:10.1016/j.jchf.2020.03.004. PMID 32360242 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Xiong TY, Redwood S, Prendergast B, Chen M (2020). "Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: acute and long-term implications". Eur Heart J. 41 (19): 1798–1800. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231. PMID 32186331 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Musher DM, Abers MS, Corrales-Medina VF (2019). "Acute Infection and Myocardial Infarction". N Engl J Med. 380 (2): 171–176. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1808137. PMID 30625066.

- ↑ Chen C, Zhou Y, Wang DW (2020). "SARS-CoV-2: a potential novel etiology of fulminant myocarditis". Herz. 45 (3): 230–232. doi:10.1007/s00059-020-04909-z. PMC 7080076 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32140732 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ 10.0 10.1 Jabri A, Kalra A, Kumar A, Alameh A, Adroja S, Bashir H, Nowacki AS, Shah R, Khubber S, Kanaa'N A, Hedrick DP, Sleik KM, Mehta N, Chung MK, Khot UN, Kapadia SR, Puri R, Reed GW (July 2020). "Incidence of Stress Cardiomyopathy During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic". JAMA Netw Open. 3 (7): e2014780. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14780. PMC 7348683 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32644140 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ 11.0 11.1 Minhas AS, Scheel P, Garibaldi B, Liu G, Horton M, Jennings M, Jones SR, Michos ED, Hays AG (May 2020). "Takotsubo Syndrome in the Setting of COVID-19 Infection". JACC Case Rep. doi:10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.023. PMC 7194596 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32363351 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ [+https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950 "Association of Cardiac Injury With Mortality in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in Wuhan, China | Global Health | JAMA Cardiology | JAMA Network"] Check

|url=value (help). - ↑ Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B (March 2020). "Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study". Lancet. 395 (10229): 1054–1062. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. PMC 7270627 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32171076 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Kociol RD, Pang PS, Gheorghiade M, Fonarow GC, O'Connor CM, Felker GM (2010). "Troponin elevation in heart failure prevalence, mechanisms, and clinical implications". J Am Coll Cardiol. 56 (14): 1071–8. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.016. PMID 20863950.

- ↑ Saenger AK, Rodriguez-Fraga O, Ler R, Ordonez-Llanos J, Jaffe AS, Goetze JP; et al. (2017). "Specificity of B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Assays: Cross-Reactivity with Different BNP, NT-proBNP, and proBNP Peptides". Clin Chem. 63 (1): 351–358. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2016.263749. PMID 28062628.

- ↑ Gao L, Jiang D, Wen XS, Cheng XC, Sun M, He B; et al. (2020). "Prognostic value of NT-proBNP in patients with severe COVID-19". Respir Res. 21 (1): 83. doi:10.1186/s12931-020-01352-w. PMC 7156898 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32293449 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Han H, Xie L, Liu R, Yang J, Liu F, Wu K; et al. (2020). "Analysis of heart injury laboratory parameters in 273 COVID-19 patients in one hospital in Wuhan, China". J Med Virol. 92 (7): 819–823. doi:10.1002/jmv.25809. PMC 7228305 Check

|pmc=value (help). PMID 32232979 Check|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Christ-Crain M, Breidthardt T, Stolz D, Zobrist K, Bingisser R, Miedinger D, Leuppi J, Tamm M, Mueller B, Mueller C (August 2008). "Use of B-type natriuretic peptide in the risk stratification of community-acquired pneumonia". J. Intern. Med. 264 (2): 166–76. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01934.x. PMID 18298480.

- ↑ Mueller C, Laule-Kilian K, Frana B, Rodriguez D, Scholer A, Schindler C, Perruchoud AP (February 2006). "Use of B-type natriuretic peptide in the management of acute dyspnea in patients with pulmonary disease". Am. Heart J. 151 (2): 471–7. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.036. PMID 16442916.

- ↑ Lai CC, Sung MI, Ho CH, Liu HH, Chen CM, Chiang SR, Chao CM, Liu WL, Hsing SC, Cheng KC (March 2017). "The prognostic value of N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome". Sci Rep. 7: 44784. doi:10.1038/srep44784. PMID 28322314.

- ↑ Determann RM, Royakkers AA, Schaefers J, de Boer AM, Binnekade JM, van Straalen JP, Schultz MJ (July 2013). "Serum levels of N-terminal proB-type natriuretic peptide in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients--relation to tidal volume size and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome". BMC Pulm Med. 13: 42. doi:10.1186/1471-2466-13-42. PMID 23837838.

- ↑ Park BH, Park MS, Kim YS, Kim SK, Kang YA, Jung JY, Lim JE, Kim EY, Chang J (August 2011). "Prognostic utility of changes in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic Peptide combined with sequential organ failure assessment scores in patients with acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome concomitant with septic shock". Shock. 36 (2): 109–14. doi:10.1097/SHK.0b013e31821d8f2d. PMID 21478812.

- ↑ Cosyns B, Lochy S, Luchian ML, Gimelli A, Pontone G, Allard SD, de Mey J, Rosseel P, Dweck M, Petersen SE, Edvardsen T (July 2020). "The role of cardiovascular imaging for myocardial injury in hospitalized COVID-19 patients". Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 21 (7): 709–714. doi:10.1093/ehjci/jeaa136. PMID 32391912 Check

|pmid=value (help). - ↑ Teerlink JR, Alburikan K, Metra M, Rodgers JE (2015). "Acute decompensated heart failure update". Curr Cardiol Rev. 11 (1): 53–62. doi:10.2174/1573403x09666131117174414. PMID 24251454.

- ↑ Seferovic PM, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, Bauersachs J, Chioncel O, Cleland J, de Boer RA, Drexel H, Ben Gal T, Hill L, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Anker MS, Lainscak M, Lewis BS, McDonagh T, Metra M, Milicic D, Mullens W, Piepoli MF, Rosano G, Ruschitzka F, Volterrani M, Voors AA, Filippatos G, Coats A (October 2019). "Clinical practice update on heart failure 2019: pharmacotherapy, procedures, devices and patient management. An expert consensus meeting report of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology". Eur. J. Heart Fail. 21 (10): 1169–1186. doi:10.1002/ejhf.1531. PMID 31129923. Vancouver style error: initials (help)

- ↑ Bleumink GS, Feenstra J, Sturkenboom MC, Stricker BH (2003). "Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and heart failure". Drugs. 63 (6): 525–34. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363060-00001. PMID 12656651.