| Margaret Sanger | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Born | September 14, 1879 Corning, New York | ||

| Died | September 6, 1966 Tucson, Arizona[1] | ||

| Spouse | William Sanger, James Noah H. Slee[1] | ||

Margaret Sanger (September 14, 1879 – September 6, 1966) was an American feminist and eugenics activist, who founded the American Birth Control League, which eventually became Planned Parenthood; she retired from the organization in 1940. She is commonly criticized for her legacy of antiblack racism.

Her main success was in bringing discussions of birth control into the public arena. She blamed large families for all of the ills of society,[2] and argued that a major reason to promote birth control was to stop abortions.[3] She was vigorously denounced by the Catholic Church because of her position on birth control.

As is common with progressives, Sanger believed that big government must have a role.[4]

Contents

Early life and family[edit]

Sanger was born on September 14, 1879 in Corning, New York as Margaret Louise Higgins[5] to Michael Hennessey Higgins and Anne Purcell Higgins.[6] Her brothers and sisters were: Ethel, Henry, John, Joseph, Lawrence, Mary, Nan, Richard, Robert, and Thomas.[7][8]

Among Sanger's siblings, her brother Robert("Bob") was a well known football player who was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954.[9] Her sister Ethel Higgins Byrne was a radical feminist activist like Margaret was.[10] When Margaret was nineteen years old, her mother Anne passed away from Tuberculosis at the age of fifty. But Margaret was already at this time blaming all of the problems of the world on overpopulation and large families. At the funeral, she exploded toward her father, blaming him for her death. "You caused this. Mother is dead from having too many children!"[11]

In 1896, she was enrolled in Claverack College and Hudson River Institute by her parents. Her tuition was initially paid for by two of her sisters.[12] As a young adult, Margaret attended nursing school at the White Plains Hospital in New York.[13]

During this time, in 1902, married William Sanger, who was an architect by trade.[14] Together, Margaret and William were active radicals in New York's Greenwich Village scene.[14][15] Bill Sanger was active in the Socialist Party of the Bronx.[16] They had three children together: Grant, Stuart, and Peggy. In 1903, after the birth of their first son, Margaret was diagnosed with Tuberculosis, the disease that had killed her own mother.[17] The Sangers waited five years for Margaret to recover from the disease before having their second and third children. Their daughter Peggy died young at the age of five from pneumonia.[18] Margaret became estranged from William in 1913.[19]

William, who was a radical like Margaret, was arrested in a sting operation for dispersing one of her pamphlets, Family Limitation,[20] for which he spent 30 days in jail. They divorced in 1921.

A year after her divorce from William Sanger, Margaret remarried to Noah Slee.[21] Like her first husband Bill, J. Noah was also of an activist mindset, helping Margaret achieve her objectives.

Early influence[edit]

Her father Michael was an atheist and an outspoken Georgist activist. He had read Henry George's work Progress and Poverty and supported the Single Tax movement.[22] The influence of George was so profound in the Higgins family that one of Sanger's brothers was named Henry George McGlynn Higgins. This is significant in not only the obvious Henry George naming, but the second middle name of "McGlynn" is a reference to Edward McGlynn, a popular Catholic priest in New York who was excommunicated for his outspoken support of Georgist ideals.[23]

Her mother Anne had 18 pregnancies, with 11 of them being born.[24] In her autobiography, Sanger recalled that even as a child she blamed big families as the main reason for society's ills. She wrote:

Large families were associated with poverty, toil, unemployment, drunkenness, cruelty, fighting, jails; the small ones with cleanliness, leisure, freedom, light, space, sunshine.

The fathers of the small families owned their homes; the young-looking mothers had time to play croquet with their husbands in the evenings on the smooth lawns. Their clothes had style and charm, and the fragrance of perfume clung about them. They walked hand in hand on shopping expeditions with their children, who seemed positive in their right to live. To me the distinction between happiness and unhappiness in childhood was one of small families and of large families rather than of wealth and poverty.[25]

Sadie Sachs[edit]

In her autobiography, Sanger lists the case of Sadie Sachs (a possibly fictional story) as having a deeply profound effect on her outlook.[26] According to the account, Sachs paid to have a backroom abortion for which the doctor botched the procedure. After recovering from an infection, Sachs consulted with the doctor as to how to how to prevent pregnancy and save her own life. The reply from the doctor was presumably that Jake, her husband, should be told to sleep on the roof.[27] Sadie became pregnant shortly after that, attempted to conduct a premature abortion on her own, and shortly died in the presence of Sanger.

Activism[edit]

After several years in Westchester, New York, Margaret and William Sanger's house at Hastings-on-Hudson was destroyed in a fire.[28] After the fire the house was rebuilt, but "A new spirit was awakening within me", and she began her new life as a social activist. When the Sangers moved to New York City, William went looking for work to sustain the family, but Margaret joined several socialist organizations and activities. In 1913 she joined the Women's Committee of the Socialist Party of New York,[29] and would eventually become a committee chair.[30]

Feminism[edit]

Sanger argued for woman's liberation from the domination of men. She advocated economic independence and withdrawal from the traditional family unit, particularly marriage. She wrote “No woman can call herself free who does not own and control her body. No woman can call herself free until she can choose consciously whether she will or will not be a mother.” [31] (see self-realization). In 1911-1913, Sanger contributed articles for the New York Call, a socialist daily newspaper. Her columns were titled "What Every Mother Should Know" (1911–12) and "What Every Girl Should Know" (1912–13).[32][33]

Free Speech League[edit]

During the time of William and Margaret Sanger's activist phase while living in Greenwich Village, she became involved with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), befriending socialists, intellectuals, and left wing artists such as Mabel Dodge Luhan, John Reed, Upton Sinclair, and Emma Goldman. She also participated in strikes such as the 1912 Lawrence textile strike and the 1913 Paterson silk strike.[34][35] At the same time, the Greenwich bohemians were beginning to take up the cause of birth control, making them and the Sanger family natural allies.[36] Margaret would become a leader within the self-styled "Free Speech movement".[37]

Emma Goldman, Ezra Heywood, Moses Harman, D. M. Bennett, and other well known radicals of the "Free Speech League", like Margaret Sanger, sought to undermine and overturn the Comstock laws using subversive and demagogic means[38] in addition to their support for the cause of birth control.[39]

After being introduced to important members of the league such as Edward Bliss Foote and Theodore Schroeder, the league helped provide her with future legal assistance. The president of the league, Leonard D. Abbott,[40] and the league's attorney Gilbert E. Roe frequently acted as her lawyers during trial.[41]

In 1914, Sanger proved herself to be a radical's radical. While associated with the Free Speech League, she launched the magazine The Woman Rebel, which she new would provoke anti-obscenity laws such as the Comstock Law due to its (for the time) graphic sexual content.[42] Additionally, the magazine carried the slogan "No gods, no masters", which was a slight change from an IWW slogan: "No God, No Master."[43]

Seeking publicity for her cause, she sent seven issues of the Rebel through the mail before the Post Office finally responded. This led to the magazine being banned - an outcome she sought - and she was subsequently arrested.[44] She eventually was let out on bail and quickly fled the country.

While Sanger was overseas in exile, supportive radicals Emma Goldman and Ben Reitman continued distributing her pamphlet Family Limitation while conducting a nationwide speaking tour.[45]

Europe[edit]

After fleeing the country for England, Sanger met notable Fabian Socialists who helped her refine her craft. George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Havelock Ellis, among others. Ellis in particular taught her to tone down her rhetoric. Ellis guided her to use a more cautious and prudent propaganda,[46] taking advantage of the language of social sciences but with a sharper emotional guile. She was also influenced by Neo-Malthusian writings. While in Europe, she met Charles Vickery Drysdale, who would go on to be a co-founder of the British Family Planning Association. While at a Fabian Society meeting, Sanger also met Marie Stopes, who, like Drysdale, was an early pioneer in the field of birth control. Stopes was also a Neo Malthusian. Stopes sought out Sanger's advice for her book Married Love.[47] Stopes considered Sanger to be an inspiration, and included a bit about contraception in the book.

A trip to Holland led Sanger to conclude that the fight for birth control would need to take on greater medical tones, instead of being a "free speech fight".[46] When she returned to America, she increasingly moved further away from her former radical friends, such as her former anarchist and communist friends in the IWW. Sanger explained: "I am determined to bide my time, consolidate my forces, continue my studies, my lectures, my letters to the countless women who are writing me every week."[46] Sanger had fully taken in the Fabian viewpoint of the Inevitability of Gradualness. She eventually developed the viewpoint that Marxism was nothing more than a fad religion, and wholly rejected it.[48]

Birth control[edit]

Early activism[edit]

Margaret Sanger and Otto Bobsein coined the term "birth control".[49][50] Before she returned to the States, Sanger was offered a position on the executive committee of the National Birth Control League (NBCL), the first birth control organization in the United States.[51] The NBCL was founded in 1915 by Mary Ware Dennett, Jessie Ashley, and Clara Gruening Stillman.[52]

In October 1916, Sanger opened and (illegally) operated the first birth control clinic in the United States, in Brooklyn, New York. It was raided by the police, and shut down. Sanger was sentenced to 30 days imprisonment for distributing contraceptives, which were illegal at the time.

In 1917, Sanger established the magazine Birth Control Review. In 1921, she founded the organization for which she would become most widely known - the American Birth Control League (ABCL).[53] Two years later, she founded the Clinical Research Bureau (CRB).[54] In 1929, as a result of differences between other leaders of the birth control movement, Sanger resigned her leadership position within the ABCL and assumed full control of the CRB.[55] At the same time, the CRB was renamed to the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau (BCCRB).

J. Noah Slee and Holland-Rantos[edit]

In the mid-late 1920s, her husband Noah Slee began smuggling diaphragms into New York through Canada[56] in boxes labeled as 3-In-One Oil.[57] He later became the first legal manufacturer of diaphragms in the United States[58] beginning with his fifteen thousand dollar investment into Holland-Rantos(HR).[59] Behind the scenes,[60][61] Margaret was a major force for the creation of the company. The creation of HR also served another purpose, using free markets to legitimize her efforts. Early on in Sanger's activism, birth control items were primarily available through black market channels. The Slee's successfully reinvented it into a reputable, "capitalist business".[59] Herbert Simonds was a founding partner of Holland-Rantos.[62]

Harlem clinic[edit]

Working with the Urban League in 1929, Sanger opened up the first birth control clinic in Harlem, New York.[63] That same year, Sanger established the National Committee on Federal Legislation for Birth Control as a lobbying organization, in order to influence the creation and amendment of laws pertaining to abortion and birth control.[64] It was closed in 1937, only six months after the court case United States v. One Package of Japanese Pessaries.[65]

Meeting with Gandhi[edit]

In 1936, Sanger met with Mahatma Gandhi while on a visit to India.[66] During their debate, Gandhi surprised her by rejecting her arguments. Gandhi was of the belief that love becomes lust if it is for the purpose of satisfaction. For Gandhi, men should endeavor to rise above animality and carnal satisfaction. He opposed artificial birth control and preached abstinence.[66]

Rich donors and deep pockets[edit]

During her tenure as leader of the birth control movement, Sanger was very adept at gaining the support of wealthy donors. In 1924 and again in 1925, John D. Rockefeller Jr. donated five thousand dollars to the ABCL.[67] Others she frequently associated with were Mary Lasker, who became wealthy from her husband's advertisements in the tobacco industry; Clarence Gamble, heir to the Procter and Gamble company;[68] and Katherine McCormick, heir to the McCormick fortune.

Organizational mergers[edit]

After the resolution of differences a decade earlier, the BCCRB and the ABCL merged in 1938 to form the short-lived Birth Control Federation of America.[69] The organization changed it's name to Planned Parenthood in 1942.

When the organization changed its name to Planned Parenthood, Sanger was very displeased. Even in the smallest degree, it potentially encourages having more children.[70] She wrote:

It irks my very soul and all that is Irish in me to acquiesce to the appeasement group that is so prevalent in our beloved organization.

Ideology[edit]

She believed that some people should be 100% barred from procreation of any kind, rather than limited encouragement that could produce the wrong kind of people, if, albeit, less of them.[71] She said as much, in a video that surfaced in 2014 from a 1947 One Minute News interview she was in with John Parsons of British Pathé. In the footage, she called for a 10-year ban on babies, insisting that it is both practical and humane.[72][73][74] She again made similar comments in 1957 in an interview with Mike Wallace of ABC. Wallace asked her if she believed in the existence of sin and her response was that "I think the greatest sin in the world is bringing children into the world" - and after a few second uncomfortable pause she said "that have disease from their parents, that have no chance in the world to be a human being practically. Delinquents, prisoners, all sorts of things, just marked when they’re born. That, to me, is the greatest sin that people can commit."[75] At other times, she called for sterilization, a baby code, and a better distribution of babies.[76]

The pill[edit]

During the 1950s, Sanger worked with Katharine McCormick to fund the research being conducted by Gregory Pincus to develop The pill. A few years later, Enovid was the first birth control formulation submitted for FDA approval.[77]

International work[edit]

Over time, Sanger increasingly wanted to work on an international level. Sanger worked to spread her work in Japan, through her contact with Shidzue Katō.[78] She made an impact in China, working with Pearl Buck to establish a clinic in Shanghai.[79] And in 1953, she established in India the International Planned Parenthood Committee, which would become the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF).[80] C. P. Blacker, a prominent eugenist, was the first administrative chairman of the IPPF.[81]

Overpopulation[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see Malthusianism.

Sanger was a believer in the doctrines of Robert Malthus, and early on, this caused problems for her newly formed magazine.[82] She frequently wrote that too much population was the cause of unemployment, poverty, crime, and war, and she would often issue challenges to people to provide realistic solutions to overpopulation.[83]

In 1925, she organized the Sixth International Neo-Malthusian and Birth-Control Conference together with the American Birth Control League.[84][85] In 1927, encouraged by George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells,[86] she organized the first World Population Conference in Geneva.[87]

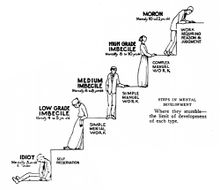

Eugenics and race[edit]

Margaret Sanger campaigned for eugenic controls to enforce what she called "race hygiene" and was a member of the American Eugenics Society and the English Eugenics Society.[88][89][90]

Many modern ideas of the substandard morals and inferiority of particular races are echoed in Sanger's writings. She wrote in one of her "What Every Girl Should Know" commentaries, that aboriginal Australians are in her opinion "the lowest known species of the human family, just a step higher than the chimpanzee in brain development," and that they possess "so little sexual control that police authority alone prevents him from obtaining sexual satisfaction on the streets." She compared these aborigines to "normal man and Woman" who have demonstrated control over their sexual desires.[91] She had a very deep hatred for other races that demonstrated a greater fecundity, such as the Chinese and the aborigines.

Additionally, she wrote about the failure of traditional ethics in sexuality that "... have in the past revealed their woeful inability to prevent the sexual and racial chaos into which the world has today drifted."[92]

Margaret Sanger associated with racists[93] and even held a close personal relationship with klansman and Nazi sympathizer Lothrop Stoddard, co-founding the American Birth Control League along with him and a few others. In 1926, she was the guest speaker at a Ku Klux Klan rally in Silverlake, New Jersey.[94] Despite these and many other things, her views on race have been intensely debated over the years. One Sanger biographer even wrote that "Margaret Sanger was never herself a racist, but she lived in a profoundly bigoted society, and her failure to repudiate prejudice - especially when it was manifest among proponents of her cause - has haunted her ever since."[95]

Affairs[edit]

According to the Margaret Sanger Papers Project, Sanger conducted "a series of affairs with several men, including Havelock Ellis and H.G. Wells".[96] Her affair with H. G. Wells[97] is probably the most well known, however she is also known to have had affairs with Herbert Simonds,[98] Harold Hersey,[99] Lorenzo Portet,[100] Harold Child,[101][102] Hugh de Selincourt,[103] and Angus Macdonald.[104]

Her affair with Havelock Ellis probably had the most immediate devastating effect. Sanger first met Ellis in December 1914, and just a few weeks later they were sending each other passionate letters.[105] One letter read "I still love all that I have loved, and even if I loved another I should still love you". Ellis' wife Edith was on a speaking tour in America when Havelock mentioned Margaret to her in correspondence. Edith suffered both a physical and nervous breakdown and returned to England.

She passed away the following year.[105]

Death and legacy[edit]

Sanger died in Tucson, Arizona on September 6, 1966,[1] of complications from congestive heart failure.[106] She was 86 years old.[107] She is buried in the prestigious Green-Wood Cemetery in Sunset Park, Brooklyn.[108]

Planned Parenthood annually gives awards to those who support them and the top award they give is called The Margaret Sanger Award.[109][110] Alan Guttmacher, who was a President of Planned Parenthood from 1962 to 1974 and who was also former Vice-President of the American Eugenics Society,[111][112] stated: "We are merely walking down the path that Ms. Sanger has carved out for us." [113][114] Similarly, Faye Wattleton, who was the president of Planned Parenthood until 1992, stated that she was "proud" to be "walking in the footsteps" of Margaret Sanger.[114] In 1960, Sanger was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize.[115]

Dr. William Moulton Marston developed the character Wonder Woman through his inspiration of Sanger.[116]

A request was sent to the Smithsonian Institution for a bust of Sanger currently on display in a "Struggle for Justice" exhibit. The bust was a gift of Cordelia Scaife May.[117] The request, led by a group of Black pastors, noted that Sanger has previously spoke in front of the KKK, as well as a long line of racist viewpoints.[118][119][120] One reason the Smithsonian refused the request was because of her role in Women's rights. The pastors noted that it would make more sense to place the bust in an exhibit together with "with busts of Pharaoh, Herod, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, Goebbels, Pol Pot, and Dr. Mengle," in order to "put her in proper historical context with the infamous and evil figures who committed genocide."[121]

Overshadowed by her well known activism in the arena of birth control and the organization Planned Parenthood, is Sanger's support for Euthanasia. During the 1950s, Sanger was a member of the advisory council for the Euthanasia Society of America.[122]

On April 20, 2016, US Treasury secretary Jack Lew announced that Harriet Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson on the front of the $20 bill,[123] for which Margaret Sanger was a contender.[124]

The Planned Parenthood of Greater New York announced in July that they would rename their headquarters, due to Sanger's racism and promotion of eugenics.[125] In a statement, they said: "Margaret Sanger's concerns and advocacy for reproductive health have been clearly documented, but so too has her racist legacy."

Quotes[edit]

- "I just don't see how we can control the birth rate until we get the government to agree that this is something that should be taken seriously. Other countries feel that if our country is against it, it must be bad. Americans would be much more acceptable when they go abroad to work on the problem if we get our government to okay it under population control." [4]

- "The most merciful thing that the large family does to one of its infant members is to kill it." [126]

- "All of our problems are the result of overbreeding among the working class, and if morality is to mean anything at all to us, we must regard all the changes which tend toward the uplift and survival of the human race as moral." [2]

- "Those least fit to carry on the race are increasing most rapidly. People who cannot support their own offspring are encouraged by Church and State to produce large families. Many of the children thus begotten are diseased or feebleminded; many become criminals. The burden of supporting these unwanted types has to be borne by the healthy elements of the nation. Funds that should be used to raise the standard of our civilization are diverted to the maintenance of those who should never have been born." - Statement of the American Birth Control League[127]

- "The mass of significant Negroes, particularly in the South, still breed carelessly and disastrously, with the result that the increase among Negroes, even more than among whites, is [in] that portion of the population least intelligent and fit and least able to rear children properly." - Margaret Sanger - The "Negro Project" quoting W.E.B. DuBois with the omission of one word [128]

- "Always to me any aroused group was a good group, and therefore I accepted an invitation to talk to the women's branch of the Ku Klux Klan at Silver Lake, New Jersey, one of the weirdest experiences I had in lecturing."[129][130]

- "Before eugenists and others who are laboring for racial betterment can succeed, they must first clear the way for Birth Control. Like the advocates of Birth Control, the eugenists, for instance, are seeking to assist the race toward the elimination of the unfit. Both are seeking a single end but they lay emphasis upon different methods."[131][132]

- "Organized charity is itself the symptom of a malignant social disease. Those vast complex, interrelated organizations aiming to control and to diminish the spread of misery and destitution and all the menacing evils that spring out of this sinisterly fertile soil, are the surest sign that our civilization has bred, is breeding and is perpetuating constantly increasing numbers of defectives, delinquents and dependents. My criticism therefore, is not directed at the ‘failure’ of philanthropy, but rather at its success" - Margaret Sanger, The Pivot of Civilization [NY: Brentano's, 1922], (p. 108).[133]

- "To each group we explained what contraception was; that abortion was the wrong way—no matter how early it was performed it was taking life; that contraception was the better way, the safer way—it took a little time, a little trouble, but was well worth while in the long run, because life had not yet begun."[134]

- "Of all lands China needed knowledge of how to control her numbers; the incessant fertility of her millions spread like a plague. Well-wishing foreigners who had gone there with their own moral codes to save her babies from infanticide, her people from pestilence, had actually increased her problem. To contribute to famine funds and the support of missions was like trying to sweep back the sea with a broom." [135]

- "The lack of balance between the birth of the "unfit" and the "fit," admittedly greatest present menace to civilization, never be rectified by the inauguration of cradle competition between these two classes. The example of the inferior classes, the fertility of the feeble-minded, the mentally defective, the poverty-stricken, should not be held up emulation to the mentally and physically fit, and therefore less fertile, parents of the educated and well-to-do-classes. On the contrary, the most urgent problem today is how to limit and discourage the over fertility of the mentally and physically defective. Possibly drastic and Spartan methods may be forced upon American society if it continues complacently to encourage the chance and chaotic breeding that has resulted from our stupid, cruel sentimentalism."[136]

- "Our whole philosophy is, in fact, based upon the fundamental assumption that man is a self-conscious, self-governing creature, that he should not be treated as a domestic animal; that he must be left free, at least within certain wide limits, to follow his own wishes in the matter of mating and in the procreation of children. Nor do we believe that the community could or should send to the lethal chamber the defective progeny resulting from irresponsible and unintelligent breeding." [137]

- "Birth control is not contraception indiscriminately and thoughtlessly practiced. It means the release and cultivation of the better racial elements in our society, and the gradual suppression, elimination and eventual extirpation of defective stocks - those human weeds which threaten the blooming of the finest flowers of American civilization."[138]

- "Just think for a moment of the meaning of the word kindergarten--a garden of children! To me, that is just what the world ought to be--a garden of children. In this matter we should not do less than follow the example of the professional gardener. Every expert gardener knows that the individual plant must be properly spaced, rooted in a rich nourishing soil, and provided with sufficient air and sunlight. He knows that no plant would have a fair chance of life if it were overcrowded or choked by weeds. To grow into maturity, to bud, to blossom, to produce beautiful sturdy flowers in its own season, each plant must have constant attention, incessant care and tender devotion. If plants, and livestock as well, require space and air, sunlight and love, children need them even more. The only real wealth of our country lies in the men and women of the next generation. A farmer would rather produce a thousand thoroughbreds than a million runts. How are we to breed a race of human thoroughbreds unless we follow the same plan? We must make this country into a garden for children instead of a disorderly back lot overrun with human weeds. In a home where there are too many children in proportion to the living space, the air and sunlight, the children are usually overcrowded and underfed. They are a constant burden on their mother's overtaxed strength and the father's earning capacity. Such homes cannot be gardens in any sense of the word."[139]

- In Margaret Sanger's book The Pivot of Civilization she also called for the elimination of "human weeds," for the segregation of "morons, misfits, and maladjusted," and for the sterilization of "genetically inferior races." [140]

In her book The Case for Birth Control, quoting approvingly of Havelock Ellis:[141]

- "If it were necessary to choose between the task of getting children educated and the task of getting them well born and healthy, it would be better to abandon education."

Works[edit]

- What Every Mother Should Know, (1911)

- Family Limitation, (1914)

- What Every Girl Should Know, (1916)

- The Case for Birth Control: A Supplementary Brief and Statement of Facts, (1917)

- Woman and the New Race, (1920)

- Debate on Birth Control, (1921)

- The Pivot of Civilization, (1922)

- Motherhood in Bondage, (1928)

- My Fight for Birth Control, (1931)

- An Autobiography, (1938)

Sources[edit]

- Douglas, Emily Taft (1970), Margaret Sanger; Pioneer of the Future, New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston

- Lader, Lawrence (1955), The Margaret Sanger Story and the Fight for Birth Control, Greenwood Press

- Peterson, Jefferis Kent (2007), Abortion - A Liberal Cause?, Erik Rauch (MIT) Retrieved on 2007-07-25

- Sanger, Margaret (1920), Women and the New Race, New York, NY: Truth Publishing Company Facsimile retrieved on 2007-07-24

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Margaret Sanger Is Dead at 82; Led Campaign for Birth Control

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 MORALITY AND BIRTH CONTROL

- ↑ BIRTH CONTROL OR ABORTION?,

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Founder pessimistic about birth control

- ↑ Margaret Sanger

- ↑ A to Z of American Women Leaders and Activists

- ↑ Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America

- ↑ Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion

- ↑ Robert A. "Bob, The Hig" Higgins

- ↑ Dorothy Day: Champion of the Poor

- ↑ Their Angry Creed: The shocking history of feminism, and how it is destroying our way of life

- ↑ Margaret Sanger

- ↑ Margaret Sanger, Nancy Whitelaw

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: MMWR, Volume 48, Issues 25-52

- ↑ People & Events: Greenwich Village Intellectuals in the Early 20th Century

- ↑ Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Birth Control

- ↑ Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion

- ↑ Public Health: The Development of a Discipline, Volume 1

- ↑ Birth Control in America: The Career of Margaret Sanger

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of New York State

- ↑ Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion

- ↑ Henry George Dr. Edward McGlynn & Pope Leo XIII

- ↑ Women Criminals: An Encyclopedia of People and Issues (2 volumes): An Encyclopedia of People and Issues

- ↑ The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger, Margaret Sanger

- ↑ Birth Control in America: The Career of Margaret Sanger

- ↑ Sterilized by the State: Eugenics, Race, and the Population Scare in Twentieth-Century North America

- ↑ Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion

- ↑ Contraception: A History

- ↑ To Be Young Was Very Heaven: Women in New York Before the First World War

- ↑ II. Women’s Struggle for Freedom

- ↑ What Every Mother Should Know: Or How Six Little Children Were Taught the Truth.

- ↑ What Every Girl Should Know

- ↑ CQ Press Guide to Radical Politics in the United States

- ↑ The Paterson Strike, by Margaret H. Sanger

- ↑ Freedom of Speech: Rights and Liberties Under the Law

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to Modern American Culture

- ↑ CQ Press Guide to Radical Politics in the United States

- ↑ Pioneers of Birth Control in England and America, American Propagandists

- ↑ The Twentieth Century Magazine, Volume 4, 1911

- ↑ Free Speech in Its Forgotten Years, 1870-1920

- ↑ Written by Herself: Volume I: Autobiographies of American Women: An Anthology

- ↑ Women's Periodicals in the United States: Social and Political Issues

- ↑ Margaret Sanger (1879–1966)

- ↑ Emma Goldman: Anarchist Woman

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 The Birth Control Movement and American Society: From Private Vice to Public Virtue

- ↑ The Public Lives of Charlotte and Marie Stopes

- ↑ Teaching America about Sex: Marriage Guides and Sex Manuals from the Late Victorians to Dr. Ruth

- ↑ Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America

- ↑ The Pivot of Civilization in Historical Perspective: The Birth Control Classic

- ↑ Birth Control in America: The Career of Margaret Sanger

- ↑ Once Upon a Pedestal

- ↑ Social Issues in America: An Encyclopedia

- ↑ Broadcasting Birth Control: Mass Media and Family Planning

- ↑ The Progressive Era's Health Reform Movement: A Historical Dictionary

- ↑ Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America

- ↑ Thinking Out Loud: On the Personal, the Political, the Public and the Private

- ↑ Margaret Sanger - 20th Century Hero, p. 8, Planned Parenthood

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion

- ↑ The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger: Birth control comes of age, 1928-1939, p. 47, footnote 9

- ↑ Sanger's Role in the Development of Contraceptive Technologies

- ↑ Ideas triumphant: strategies for social change and progress

- ↑ Women and Health in America: Historical Readings

- ↑ Life, Death and the Law: Law and Christian Morals in England and the United States

- ↑ Lobbying for Birth Control

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 The Cultural Construction of Sexuality

- ↑ Cannot Be Silenced

- ↑ Margaret Sanger: A Life of Passion

- ↑ Gender and Women's Leadership: A Reference Handbook, Volume 1

- ↑ The Birth Control Movement and American Society: From Private Vice to Public Virtue

- ↑ The Birth Control Movement and American Society: From Private Vice to Public Virtue, See footnote 49

- ↑ Shocking new footage found of Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger saying "no more babies", Live Action

- ↑ Ban on Babies is All Wet, Cry Angry Britons, Chicago Tribune

- ↑ "No More Babies!" - Expert Calls For Ban on Childbirth (1947), British Pathé

- ↑ Planned Parenthood Founder: 'Greatest Sin...is Bringing Children Into the World That Have Disease', CNSNews.com

- ↑ America Needs a Code for Babies, A Plea for Equal Distribution of Births by Margaret Sanger; March 27, 1934

- ↑ Timeline: The Pill, PBS

- ↑ Facing Two Ways: The Story of My Life

- ↑ Profiles in Humanity: The Battle for Peace, Freedom, Equality, and Human Rights

- ↑ Margaret Sanger's Eugenic Legacy: The Control of Female Fertility

- ↑ Eugenics, Literature, and Culture in Post-war Britain

- ↑ Margaret Sanger

- ↑ Margaret Sanger

- ↑ Margaret Sanger's Eugenic Legacy: The Control of Female Fertility

- ↑ The Correspondence of W. E. B. Du Bois: Selections, 1877-1934

- ↑ The Feminist Revolution: A Story of the Three Most Inspiring and Empowering Women in American History: Susan B. Anthony, Margaret Sanger, and Betty Friedan

- ↑ The State and the Stork: The Population Debate and Policy Making in US History

- ↑ http://www.all.org/abac/contents.txt

- ↑ http://www.lifeadvocate.org/1_98/feature.htm

- ↑ Angry White Female: Margaret Sanger's Race of Thoroughbreds

- ↑ What Every Girl Should Know, Sexual Impulse - Part II

- ↑ Birth Control Review, Volume 5, The Eugenic Value of Birth Control Propaganda

- ↑ Peterson 2007

- ↑ Peterson 2007 citing Douglas 1970, p. 192

- ↑ Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America

- ↑ Biographical Sketch

- ↑ Radical Womanhood: Feminine Faith in a Feminist World

- ↑ MARGARET SANGER: FEMINIST HEROINE, PUBLIC NUISANCE, OR SOCIAL ENGINEER?, California State University

- ↑ Woman of Valor: Margaret Sanger and the Birth Control Movement in America

- ↑ "lorenzo+portet" Margaret Sanger and the Origin of the Birth Control Movement, 1910-1930: The Concept of Women's Sexual Autonomy

- ↑ "harold+child" Havelock Ellis: a biography

- ↑ British Reform Writers, 1832-1914, Volume 190

- ↑ The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger, Volume 4: Round the World for Birth Control, 1920-1966

- ↑ The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger: Birth control comes of age, 1928-1939, p. 229

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 The Birth Control Movement and American Society: From Private Vice to Public Virtue

- ↑ Margaret Sanger 1879 - 1966, The founder of the birth-control movement in the United States

- ↑ Margaret Sanger Is Dead at 82; Led Campaign for Birth Control, The New York Times

- ↑ The Graveyard Shift: A Family Historian's Guide to New York City Cemeteries

- ↑ Allan Rosenfield Receives the Reproductive Rights Movement's Highest Honor - Planned Parenthood Federation of America's Margaret Sanger Award

- ↑ PPFA Margaret Sanger Award Winners

- ↑ What is Roe v. Wade?

- ↑ Eugenics Watch

- ↑ What the Facts Reveal About Planned Parenthood

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 The Inherent Racism of Population Control By Paul Jalsevac

- ↑ Nomination Database

- ↑ The Man Behind Wonder Woman Was Inspired By Both Suffragists And Centerfolds

- ↑ NPG.72.70

- ↑ Smithsonian Refuses Request from Black Pastors to Remove Bust of Eugenicist Planned Parenthood Founder

- ↑ Smithsonian Refuses to Remove Margaret Sanger Statue: We Don’t Care She Was a Eugenicist, LifeNews.com

- ↑ Conservatives Want Bust of Planned Parenthood Founder Removed From National Portrait Gallery, Time magazine

- ↑ Smithsonian Won't Remove Bust of Margaret Sanger, Christian Broadcasting Network

- ↑ Legacy of death: Abortion, eugenics, euthanasia groups shared board members, Live Action

- ↑ Tubman replacing Jackson on the $20, Hamilton spared

- ↑ Women on 20's

- ↑ Planned Parenthood to remove Margaret Sanger's name from center over 'racist legacy'

- ↑ Sanger 1920, p. 63, see also Transcript.

- ↑ Birth Control: What it Is, how it Works, what it Will Do

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/view/00147354/di975884/97p14282/1?frame=noframe&userID=80cdbf34@buffalo.edu/01cce4406300501bbf062&dpi=3&config=jstor

- ↑ Klanned Parenthood, Snopes.com

- ↑ The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger, p. 366

- ↑ Eugenics, Race, and Margaret Sanger Revisited: Reproductive Freedom for All?

- ↑ Birth Control and Racial Betterment, by Margaret Sanger

- ↑ http://www.worldwideschool.org/library/books/socl/socialconcerns/ThePivotofCivilization/chap6.html

- ↑ Margaret Sanger, An Autobiography (1938) p. 217 online

- ↑ The Autobiography of Margaret Sanger, p. 347

- ↑ The Pivot of Civilization, p. 25

- ↑ The Pivot of Civilization, p. 100

- ↑ APOSTLE OF BIRTH CONTROL SEES CAUSE GAINING HERE; Hearing in Albany on Bill to Legalize Practice a Milestone in Long Fight of Margaret Sanger -- Even China Awakening to Need of Selective Methods, She Says., The New York Times

- ↑ The Meaning of Radio Birth Control, April 1924

- ↑ Who Was Margaret Sanger

- ↑ The Case for Birth Control, by Margaret Sanger, p. 94

External links[edit]

- Fabian Hall Speech

- Works by Margaret Sanger - text and free audio - LibriVox

- The Margaret Sanger papers project at New York University

- Full interview with Mike Wallace, Harry Ransom Center

- FAVORS INCREASE OF 'SUPER-PERSONS'; Birth Conference Resolution Calls for Larger Families Among That Class. ROOSEVELT DRAWS REPLY Mrs. Sanger Says Colonel's Criticisms Are Unworthy -- Week's Work Summarized., The New York Times