| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌvɛnləˈfæksiːn/ |

| Trade names | Effexor, Efexor, others[1] |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of use | By mouth |

| Defined daily dose | 100 mg[2] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 42±15%[4] |

| Protein binding | 27±2% (parent compound), 30±12% (active metabolite, desvenlafaxine)[5] |

| Metabolism | Extensively metabolised by the liver[4][5] |

| Elimination half-life | 5±2 h (parent compound for immediate release preparations), 15±6 h (parent compound for extended release preparations), 11±2 h (active metabolite)[4][5] |

| Excretion | Kidney (87%; 5% as unchanged drug; 29% as desvenlafaxine and 53% as other metabolites)[4][5] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C17H27NO2 |

| Molar mass | 277.408 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

Venlafaxine, sold under the brand name Effexor among others, is an antidepressant medication of the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) class.[6] It is used to treat major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, and social phobia.[6] It may also be used for chronic pain.[7] It is taken by mouth.[6]

Common side effects include loss of appetite, constipation, dry mouth, dizziness, sweating, and sexual problems.[6] Severe side effects include an increased risk of suicide, mania, and serotonin syndrome.[6] Antidepressant withdrawal syndrome may occur if stopped.[6] There are concerns that use during the later part of pregnancy can harm the baby.[6] How it works is not entirely clear but it is believed to involve alterations in neurotransmitters in the brain.[6]

Venlafaxine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1993.[6] It is available as a generic medication.[6] In the United States the wholesale cost per dose is less than US$0.20 as of 2018.[8] In 2017, it was the 49th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States with more than 16 million prescriptions.[9][10]

Medical uses[edit | edit source]

Venlafaxine is used primarily for the treatment of depression, general anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, and vasomotor symptoms.[11]

Venlafaxine has been used off label for the treatment of diabetic neuropathy and migraine prevention (in some people, however, venlafaxine can exacerbate or cause migraines).[12] It may work on pain via effects on the opioid receptor.[13] It has also been found to reduce the severity of 'hot flashes' in menopausal women and men on hormonal therapy for the treatment of prostate cancer.[14][15]

Due to its action on both the serotoninergic and adrenergic systems, venlafaxine is also used as a treatment to reduce episodes of cataplexy, a form of muscle weakness, in patients with the sleep disorder narcolepsy.[16] Some open-label and three double-blind studies have suggested the efficacy of venlafaxine in the treatment of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).[17] Clinical trials have found possible efficacy in those with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[18]

Depression[edit | edit source]

A comparative meta-analysis of 21 major antidepressants found that venlafaxine, agomelatine, amitriptyline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, paroxetine, and vortioxetine were more effective than other antidepressants although the quality of many comparisons was assessed as low or very low.[19][20]

Venlafaxine was similar in efficacy to the atypical antidepressant bupropion; however, the remission rate was lower for venlafaxine.[21] In a double-blind study, patients who did not respond to an SSRI were switched to venlafaxine or citalopram. Similar improvement was observed in both groups.[22]

Studies of venlafaxine in children have not established its efficacy.[23]

Dosage[edit | edit source]

The defined daily dose is 100 mg by mouth.[2]

Contraindications[edit | edit source]

Venlafaxine is not recommended in patients hypersensitive to it, nor should it be taken by anyone who is allergic to the inactive ingredients, which include gelatin, cellulose, ethylcellulose, iron oxide, titanium dioxide and hypromellose. It should not be used in conjunction with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), as it can cause potentially fatal serotonin syndrome.[4][5][24]

Side effects[edit | edit source]

Venlafaxine can increase eye pressure, so those with glaucoma may require more frequent eye checks.[25]

Suicide[edit | edit source]

The US Food and Drug Administration body (FDA) requires all antidepressants, including venlafaxine, to carry a black box warning with a generic warning about a possible suicide risk.

A 2014 meta analysis of 21 clinical trials of venlafaxine for the treatment of depression in adults found that compared to placebo, venlafaxine reduced the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior.[26]

A study conducted in Finland followed more than 15,000 patients for 3.4 years. Venlafaxine increased suicide risk by 60% (statistically significant), as compared to no treatment. At the same time, fluoxetine (Prozac) halved the suicide risk.[27]

In another study, the data on more than 200,000 cases were obtained from the UK general practice research database. At baseline, patients prescribed venlafaxine had a greater number of risk factors for suicide (such as prior suicide attempts) than patients treated with other anti-depressants. The patients taking venlafaxine had significantly higher risk of completed suicide than the ones on fluoxetine or citalopram (Celexa). After adjusting for known risk factors, venlafaxine was associated with an increased risk of suicide relative to fluoxetine and dothiepin that was not statistically significant. A statistically significant greater risk for attempted suicide remained after adjustment, but the authors concluded that it could be due to residual confounding.[28]

An analysis of clinical trials by the FDA statisticians showed the incidence of suicidal behaviour among the adults on venlafaxine to be not significantly different from fluoxetine or placebo.[29]

Venlafaxine is contraindicated in children, adolescents and young adults. According to the FDA analysis of clinical trials[29] venlafaxine caused a statistically significant 5-fold increase in suicidal ideation and behaviour in persons younger than 25. In another analysis, venlafaxine was no better than placebo among children (7–11 years old), but improved depression in adolescents (12–17 years old). However, in both groups, hostility and suicidal behaviour increased in comparison to those receiving a placebo.[30] In a study involving antidepressants that had failed to produce results in depressed teenagers, teens whose SSRI treatment had failed who were randomly switched to either another SSRI or to venlafaxine showed an increased rate of suicide on venlafaxine. Among teenagers who were suicidal at the beginning of the study, the rate of suicidal attempts and self-harm was significantly higher, by about 60%, after the switch to venlafaxine than after the switch to an SSRI.[31]

Discontinuation syndrome[edit | edit source]

People stopping venlafaxine commonly experience discontinuation symptoms such as dysphoria, headaches, nausea, irritability, emotional lability, sensation of electric shocks, and sleep disturbance.[32] Venlafaxine has a higher rate of moderate to severe discontinuation symptoms relative to other antidepressants (similar to the SSRI paroxetine).[33]

The higher risk and increased severity of discontinuation syndrome symptoms relative to other antidepressants may be related to the short half-life of venlafaxine and its active metabolite.[34] After discontinuing venlafaxine, the levels of both serotonin and norepinephrine decrease, leading to the hypothesis that the discontinuation symptoms could result from an overly rapid reduction of neurotransmitter levels.[35]

Serotonin syndrome[edit | edit source]

The development of a potentially life-threatening serotonin syndrome (also more recently classified as "serotonin toxicity")[36] may occur with venlafaxine treatment, particularly with concomitant use of serotonergic drugs, including but not limited to SSRIs and SNRIs, many hallucinogens such as tryptamines and phenethylamines (e.g., LSD/LSA, DMT, MDMA, mescaline), dextromethorphan (DXM), tramadol, tapentadol, pethidine (meperidine) and triptans and with drugs that impair metabolism of serotonin (including MAOIs). Serotonin syndrome symptoms may include mental status changes (e.g. agitation, hallucinations, coma), autonomic instability (e.g. tachycardia, labile blood pressure, hyperthermia), neuromuscular aberrations (e.g. hyperreflexia, incoordination) or gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. nausea, vomiting, diarrhea). Venlafaxine-induced serotonin syndrome has also been reported when venlafaxine has been taken in isolation in overdose.[37] An abortive serotonin syndrome state, in which some but not all of the symptoms of the full serotonin syndrome are present, has been reported with venlafaxine at mid-range dosages (150 mg per day).[38] A case of a patient with serotonin syndrome induced by low-dose venlafaxine (37.5 mg per day) has also been reported.[39]

Pregnancy[edit | edit source]

There are few well-controlled studies of venlafaxine in pregnant women. A study released in May 2010 by the Canadian Medical Association Journal suggests use of venlafaxine doubles the risk of miscarriage.[40][41] Consequently, venlafaxine should only be used during pregnancy if clearly needed.[25] A large case-control study done as part of the National Birth Defects Prevention Study and published in 2012 found a significant association of venlafaxine use during pregnancy and several birth defects including anencephaly, cleft palate, septal heart defects and coarctation of the aorta.[42] Prospective studies have not shown any statistically significant congenital malformations.[43] There have, however, been some reports of self-limiting effects on newborn infants.[44] As with other serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), these effects are generally short-lived, lasting only 3 to 5 days,[45] and rarely resulting in severe complications.[46]

Drug interactions[edit | edit source]

Venlafaxine should be taken with caution when using St John's wort.[47] Venlafaxine may lower the seizure threshold, and coadministration with other drugs that lower the seizure threshold such as bupropion and tramadol should be done with caution and at low doses.[48]

Bipolar disorder[edit | edit source]

Venlafaxine is neither recommended nor approved for the treatment of major depressive episodes in bipolar disorder as it can induce mania or mixed episodes. Venlafaxine appears to be more likely than the SSRIs and bupropion to induce mania and mixed episodes in bipolar patients.[49]

Other[edit | edit source]

There have been false positives reported for phencyclidine (PCP), cocaine and amphetamine with routine urine-based drug tests. Although rare these instances typically occur with higher doses of venlafaxine, more than 150 mg per day, when used for extended periods of time.

In rare cases, drug-induced akathisia can occur after use in some people.[50]

Venlafaxine should be used with caution in hypertensive patients. Venlafaxine must be discontinued if significant hypertension persists.[51][52][53] It can also have undesirable cardiovascular effects.[54]

Overdose[edit | edit source]

Most patients overdosing with venlafaxine develop only mild symptoms. Plasma venlafaxine concentrations in overdose survivors have ranged from 6 to 24 mg/l, while postmortem blood levels in fatalities are often in the 10–90 mg/l range.[55] Published retrospective studies report that venlafaxine overdosage may be associated with an increased risk of fatal outcome compared to that observed with SSRI antidepressant products, but lower than that for tricyclic antidepressants. Healthcare professionals are advised to prescribe Effexor and Effexor XR in the smallest quantity of capsules consistent with good patient management to reduce the risk of overdose.[56] It is usually reserved as a second-line treatment for depression due to a combination of its superior efficacy to the first-line treatments like fluoxetine, paroxetine and citalopram and greater frequency of side effects like nausea, headache, insomnia, drowsiness, dry mouth, constipation, sexual dysfunction, sweating and nervousness.[19][57]

There is no specific antidote for venlafaxine, and management is generally supportive, providing treatment for the immediate symptoms. Administration of activated charcoal can prevent absorption of the drug. Monitoring of cardiac rhythm and vital signs is indicated. Seizures are managed with benzodiazepines or other anticonvulsants. Forced diuresis, hemodialysis, exchange transfusion, or hemoperfusion are unlikely to be of benefit in hastening the removal of venlafaxine, due to the drug's high volume of distribution.[58]

Mechanism of action[edit | edit source]

Pharmacology[edit | edit source]

| Transporter | Ki [nM][59] | IC50 [nM][60] |

|---|---|---|

| SERT | 82 | 27 |

| NET | 2480 | 535 |

| DAT | 7647 | ND |

| Receptor | Ki [nM] [61][62] | Species |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT2A | 2230 | Human |

| 5-HT2C | 2004 | Human |

| 5-HT6 | 2792 | Human |

| α1A | >1000 | Human |

Venlafaxine is usually categorized as a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), but it has been referred to as a serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI).[63][64] It works by blocking the transporter "reuptake" proteins for key neurotransmitters affecting mood, thereby leaving more active neurotransmitters in the synapse. The neurotransmitters affected are serotonin and norepinephrine. Additionally, in high doses it weakly inhibits the reuptake of dopamine,[65] with recent evidence showing that the norepinephrine transporter also transports some dopamine as well, since dopamine is inactivated by norepinephrine reuptake in the frontal cortex. The frontal cortex largely lacks dopamine transporters, therefore venlafaxine can increase dopamine neurotransmission in this part of the brain.[66][67]

Venlafaxine indirectly affects opioid receptors as well as the alpha2-adrenergic receptor, and was shown to increase pain threshold in mice. These benefits with respect to pain were reversed with naloxone, an opioid antagonist, thus supporting an opiate mechanism.[68][69]

Pharmacokinetics[edit | edit source]

Venlafaxine is well absorbed, with at least 92% of an oral dose being absorbed into systemic circulation. It is extensively metabolized in the liver via the CYP2D6 isoenzyme to desvenlafaxine (O-desmethylvenlafaxine, now marketed as a separate medication named Pristiq[70]), which is just as potent an SNRI as the parent compound, meaning that the differences in metabolism between extensive and poor metabolisers are not clinically important in terms of efficacy. Side effects, however, are reported to be more severe in CYP2D6 poor metabolisers.[71][72] Steady-state concentrations of venlafaxine and its metabolite are attained in the blood within 3 days. Therapeutic effects are usually achieved within 3 to 4 weeks. No accumulation of venlafaxine has been observed during chronic administration in healthy subjects. The primary route of excretion of venlafaxine and its metabolites is via the kidneys.[25] The half-life of venlafaxine is relatively short, so patients are directed to adhere to a strict medication routine, avoiding missing a dose. Even a single missed dose can result in withdrawal symptoms.[73]

Venlafaxine is a substrate of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), which pumps it out of the brain. The gene encoding P-gp, ABCB1, has the SNP rs2032583, with alleles C and T. The majority of people (about 70% of Europeans and 90% of East Asians) have the TT variant.[74] A 2007 study[75] found that carriers of at least one C allele (variant CC or CT) are 7.72 times more likely than non-carriers to achieve remission after 4 weeks of treatment with amitriptyline, citalopram, paroxetine or venlafaxine (all P-gp substrates). The study included patients with mood disorders other than major depression, such as bipolar II; the ratio is 9.4 if these other disorders are excluded. At the 6-week mark, 75% of C-carriers had remitted, compared to only 38% of non-carriers.[citation needed]

Chemistry[edit | edit source]

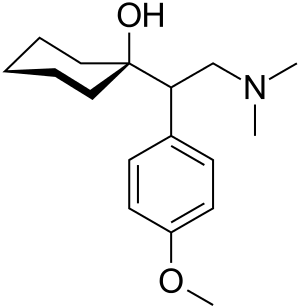

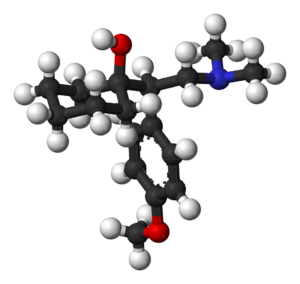

The IUPAC name of venlafaxine is 1-[2-(dimethylamino)-1-(4 methoxyphenyl)ethyl]cyclohexanol, though it is sometimes referred to as (±)-1-[a-[a-(dimethylamino)methyl]-p-methoxybenzyl]cyclohexanol. It consists of two enantiomers present in equal quantities (termed a racemic mixture), both of which have the empirical formula of C17H27NO2. It is usually sold as a mixture of the respective hydrochloride salts, (R/S)-1-[2-(dimethylamino)-1-(4 methoxyphenyl)ethyl]cyclohexanol hydrochloride, C17H28ClNO2, which is a white to off-white crystalline solid. Venlafaxine is structurally and pharmacologically related to the atypical opioid analgesic tramadol, and more distantly to the newly released opioid tapentadol, but not to any of the conventional antidepressant drugs, including tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, MAOIs, or RIMAs.[76]

Venlafaxine extended release is chemically the same as normal venlafaxine. The extended release (controlled release) version distributes the release of the drug into the gastrointestinal tract over a longer period than normal venlafaxine. This results in a lower peak plasma concentration. Studies have shown that the extended release formula has a lower incidence of nausea as a side effect, resulting in better compliance.[77]

Society and culture[edit | edit source]

Venlafaxine was originally marketed as Effexor in most of the world; generic venlafaxine has been available since around 2008 and extended release venlaxafine has been available since around 2010.[78]

As of January 2020 venlafaxine was marketed under many brand names worldwide, many with alternative extended release forms (not shown): Adefaxin, Alenthus, Altven, Alventa, Amfax, Anapresin, Ansifix, Arafaxina, Argofan, Arrow Venlafaxine, Axone, Axyven, Benolaxe, Blossom, Calmdown, Dalium, Defaxine, Depefex, Depretaxer, Deprevix, Deprexor, Deprixol, Depurol, Desinax, Dislaven, Dobupal, Duofaxin, Easyfor, Ectien, Eduxon, Efastad, Efaxin, Efaxine, Efectin, Efegen, Efevelon, Efevelone, Efexiva, Efexor, Effegad, Effexine, Effexor, Elafax, Elaxine, Elify, Enpress, Enlafax, Envelaf, Falven, Faxigen, Faxine, Faxiprol, Faxiven, Faxolet, Flavix, Flaxen, Fobiless, Ganavax, Idixor, Idoxen, Intefred, Illovex, Lafactin, Lafaxin, Lanvexin, Laroxin, Levest, Limbic, Linexel, Maxibral, Mazda, Melocin, Memomax, Mezine, Neoxacina, Neoxacina, Nervix, Norafexine, Norezor, Norpilen, Noviser, Nulev, Odiven, Olwexya, Oriven, Paxifar, Politid, Pracet, Prefaxine, Psiseven, Quilarex, Rafax, Senexon, Sentidol, Sentosa, Serosmine, Seroxine, Sesaren, Subelan, Sulinex, Sunveniz, Sunvex, Symfaxin, Tedema, Tifaxin, Tonpular, Trevilor, Tudor, Vafexin, Valosine, Vandral, Velaf, Velafax, Velahibin, Velaxin, Velept, Velpine, Venax, Venaxin, Venaxx, Vencarm, Vencontrol, Vendep, Venegis, Venex, Venexor, Venfalex, Venfax, Ven-Fax, Venfaxine, Venforin, Venforspine, Veniba, Veniz, Venjoy, Venla, Venlabax, Venlabrain, Venladep, Venladex, Venladoz, Venlaf, Venlafab, Venlafaxin, Venlafaxina, Venlafaxine, Venlagamma, Venlalic, Venlamax, Venlamylan, Venlaneo, Venlapine, Venla-Q, Venlasand, Venlatrin, Venlavitae, Venlax, Venlaxin, Venlaxine, Venlaxor, Venlazid, Venlectine, Venlifax, Venlift, Venlix, Venlobax, Venlofex, Venlor, Venorion, Venozap, Vensate, Ventab, Venxin, Venxor, Venzip, Vexamode, Vfax, Viepax, ViePax, Voxafen, Zacalen, Zanfexa, Zaredrop, Zarelis, Zarelix, and Zenexor.[1]

Cost[edit | edit source]

In the United States the wholesale cost per dose is less than US$0.20 as of 2018.[8] In 2017, it was the 49th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States with more than 16 million prescriptions.[9][10]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Venlafaxine". Drugs.com. Dallas, Texas: Drugsite Trust. January 2020. Brand Names. Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ "Efexor XL 75 mg hard prolonged release capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 16 March 2020. Archived from the original on 7 October 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "Apo-Venlafaxine XR Capsules" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Macquarie Park, NSW: Apotex Pty Ltd. 13 April 2012. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Venlafaxine (venlafaxine hydrochloride) tablet [Aurobindo Pharma Limited]". DailyMed. Aurobindo Pharma Limited. February 2013. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 "Venlafaxine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- ↑ "Antidepressants: Another weapon against chronic pain". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "NADAC as of 2018-12-19". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Venlafaxine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ "venlafaxine-hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ↑ Grothe DR, Scheckner B, Albano D (May 2004). "Treatment of pain syndromes with venlafaxine". Pharmacotherapy. 24 (5): 621–9. doi:10.1592/phco.24.6.621.34748. PMID 15162896.

- ↑ The Opioid System as the Interface between the Brain's Cognitive and Motivational Systems. Academic Press. 2018. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-444-64168-7. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Mayo Clinic staff (2005). "Beyond hormone therapy: Other medicines may help". Hot flashes: Ease the discomfort of menopause. Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 25 February 2005. Retrieved 19 August 2005.

- ↑ Schober CE, Ansani NT (2003). "Venlafaxine hydrochloride for the treatment of hot flashes". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 37 (11): 1703–7. doi:10.1345/aph.1C483. PMID 14565812.

- ↑ "Medications". Stanford University School of Medicine, Center for Narcolepsy. 7 February 2003. Archived from the original on 21 August 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ↑ Ghanizadeh A, Freeman RD, Berk M (March 2013). "Efficacy and adverse effects of venlafaxine in children and adolescents with ADHD: a systematic review of non-controlled and controlled trials". Reviews on Recent Clinical Trials. 8 (1): 2–8. doi:10.2174/1574887111308010002. PMID 23157376.

- ↑ Pae CU, Lim HK, Ajwani N, Lee C, Patkar AA (June 2007). "Extended-release formulation of venlafaxine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 7 (6): 603–15. doi:10.1586/14737175.7.6.603. PMID 17563244.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Geddes JR, Higgins JP, Churchill R, et al. (February 2009). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 373 (9665): 746–58. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. PMID 19185342.

- ↑ Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- ↑ Thase ME, Clayton AH, Haight BR, Thompson AH, Modell JG, Johnston JA (2006). "A double-blind comparison between bupropion XL and venlafaxine XR: sexual functioning, antidepressant efficacy, and tolerability". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 26 (5): 482–8. doi:10.1097/01.jcp.0000239790.83707.ab. PMID 16974189.

- ↑ Lenox-Smith AJ, Jiang Q (2008). "Venlafaxine extended release versus citalopram in patients with depression unresponsive to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 23 (3): 113–9. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e3282f424c2. PMID 18408525.

- ↑ Courtney DB (2004). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and venlafaxine use in children and adolescents with major depressive disorder: a systematic review of published randomized controlled trials". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 49 (8): 557–63. doi:10.1177/070674370404900807. PMID 15453105.

- ↑ Taylor D, Paton C, Kapur S, eds. (2012). The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry (illustrated ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 "Effexor Medicines Data Sheet". Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. 2006. Archived from the original on 17 September 2006. Retrieved 17 September 2006.

- ↑ Gibbons RD, Brown CH, Hur K, Davis J, Mann JJ (June 2012). "Suicidal thoughts and behavior with antidepressant treatment: reanalysis of the randomized placebo-controlled studies of fluoxetine and venlafaxine". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 69 (6): 580–7. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2048. PMC 3367101. PMID 22309973.

- ↑ Tiihonen J, Lönnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Tanskanen A, Haukka J (December 2006). "Antidepressants and the risk of suicide, attempted suicide, and overall mortality in a nationwide cohort". Archives of General Psychiatry. 63 (12): 1358–67. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.12.1358. PMID 17146010.

- ↑ Rubino A, Roskell N, Tennis P, Mines D, Weich S, Andrews E (2007). "Risk of suicide during treatment with venlafaxine, citalopram, fluoxetine, and dothiepin: retrospective cohort study" (PDF). British Medical Journal. 334 (7587): 242. doi:10.1136/bmj.39041.445104.BE. PMC 1790752. PMID 17164297. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Overview for December 13 Meeting of Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 16 November 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- ↑ Emslie GJ, Findling RL, Yeung PP, Kunz NR, Li Y (2007). "Venlafaxine ER for the treatment of pediatric subjects with depression: results of two placebo-controlled trials". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 46 (4): 479–88. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31802f5f03. PMID 17420682. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Brent DA, Emslie GJ, Clarke GN, Asarnow J, Spirito A, Ritz L, Vitiello B, Iyengar S, Birmaher B, Ryan ND, Zelazny J, Onorato M, Kennard B, Mayes TL, Debar LL, McCracken JT, Strober M, Suddath R, Leonard H, Porta G, Keller MB (April 2009). "Predictors of spontaneous and systematically assessed suicidal adverse events in the treatment of SSRI-resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study" (PDF). The American Journal of Psychiatry. 166 (4): 418–26. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08070976. PMC 3593721. PMID 19223438. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Petit J, Sansone RA (2011). "A case of interdose discontinuation symptoms with venlafaxine extended release". The Primary Care Companion for CNS Disorders. 13 (5). doi:10.4088/PCC.11l01140. PMC 3267502. PMID 22295261.

- ↑ Hosenbocus S, Chahal R (February 2011). "SSRIs and SNRIs: A review of the Discontinuation Syndrome in Children and Adolescents". Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 20 (1): 60–7. PMC 3024727. PMID 21286371.

- ↑ Haddad PM (March 2001). "Antidepressant discontinuation syndromes". Drug Safety. 24 (3): 183–97. doi:10.2165/00002018-200124030-00003. PMID 11347722.

- ↑ Campagne DM (2005). "Venlafaxine and Serious Withdrawal Symptoms: Warning to Drivers". Medscape General Medicine. 7 (3): 22. PMC 1681629. PMID 16369248.

- ↑ Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM (September 2003). "The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity" (PDF). QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians. 96 (9): 635–42. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg109. PMID 12925718.

- ↑ Kolecki P (July–August 1997). "Isolated venlafaxine-induced serotonin syndrome". Journal of Emergency Medicine. 15 (4): 491–3. doi:10.1016/S0736-4679(97)00078-4. PMID 9279702.

- ↑ Ebert D, et al. "Hallucinations as a side effect of venlafaxine treatment". Psychiatry On-line. Archived from the original on 21 May 2008. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ↑ Pan JJ, Shen WW (February 2003). "Serotonin syndrome induced by low-dose venlafaxine". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 37 (2): 209–11. doi:10.1345/aph.1C021. PMID 12549949.

- ↑ Broy P, Bérard A (2010). "Gestational exposure to antidepressants and the risk of spontaneous abortion: A review". Current Drug Delivery. 7 (1): 76–92. doi:10.2174/156720110790396508. PMID 19863482. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Nakhai-Pour HR, Broy P, Bérard A (2010). "Use of antidepressants during pregnancy and the risk of spontaneous abortion". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 182 (10): 1031–1037. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091208. PMC 2900326. PMID 20513781.

- ↑ Polen KN, Rasmussen SA, Riehle-Colarusso T, Reefhuis J (2013). "Association between reported venlafaxine use in early pregnancy and birth defects, national birth defects prevention study, 1997-2007". Birth Defects Res. Part a Clin. Mol. Teratol. 97 (1): 28–35. doi:10.1002/bdra.23096. PMC 4484721. PMID 23281074.

- ↑ Gentile S (2005). "The safety of newer antidepressants in pregnancy and breastfeeding". Drug Saf. 28 (2): 137–52. doi:10.2165/00002018-200528020-00005. PMID 15691224.

- ↑ de Moor RA, Mourad L, ter Haar J, Egberts AC (2003). "[Withdrawal symptoms in a neonate following exposure to venlafaxine during pregnancy]". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 147 (28): 1370–2. PMID 12892015.

- ↑ Ferreira E, Carceller AM, Agogué C, Martin BZ, St-André M, Francoeur D, Bérard A (2007). "[Effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine during pregnancy in term and preterm neonates]". Pediatrics. 119 (1): 52–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2133. PMID 17200271.

- ↑ Moses-Kolko EL, Bogen D, Perel J, Bregar A, Uhl K, Levin B, Wisner KL (2005). "Neonatal signs after late in utero exposure to serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Literature review and implications for clinical applications". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 293 (19): 2372–83. doi:10.1001/jama.293.19.2372. PMID 15900008. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Karch, A (2006). 2006 Lippincott's Nursing Drug Guide. Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, London, Buenos Aires, Hong Kong, Sydney, Tokyo: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-58255-436-5.

- ↑ Thundiyil JG, Kearney TE, Olson KR (March 2007). "Evolving epidemiology of drug-induced seizures reported to a Poison Control Center System" (PDF). Journal of Medical Toxicology. 3 (1): 15–9. doi:10.1007/BF03161033. PMC 3550124. PMID 18072153. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 July 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, Nolen WA, Grunze H, Licht RW, et al. (November 2013). "The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) task force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 170 (1): 1249–62. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13020185. PMC 4091043. PMID 24030475.

- ↑ "Venlafaxine Side Effects in Detail". Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Khurana RN, Baudendistel TE (December 2003). "Hypertensive crisis associated with venlafaxine". The American Journal of Medicine. 115 (8): 676–7. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00472-8. PMID 14656626.

- ↑ Thase ME (October 1998). "Effects of venlafaxine on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of original data from 3744 depressed patients". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 59 (10): 502–8. doi:10.4088/JCP.v59n1002. PMID 9818630.

- ↑ Edvardsson B (26 February 2015). "Venlafaxine as single therapy associated with hypertensive encephalopathy". SpringerPlus. 4 (1): 97. doi:10.1186/s40064-015-0883-0. PMC 4348355. PMID 25763307.

- ↑ Johnson EM, Whyte E, Mulsant BH, Pollock BG, Weber E, Begley AE, Reynolds CF (September 2006). "Cardiovascular changes associated with venlafaxine in the treatment of late-life depression". The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 14 (9): 796–802. doi:10.1097/01.JGP.0000204328.50105.b3. PMID 16943176.

- ↑ R. Baselt (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 1634–1637. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ↑ "Wyeth Letter to Health Care Providers". Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. 2006. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- ↑ Taylor D, Lenox-Smith A, Bradley A (June 2013). "A review of the suitability of duloxetine and venlafaxine for use in patients with depression in primary care with a focus on cardiovascular safety, suicide and mortality due to antidepressant overdose". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 3 (3): 151–61. doi:10.1177/2045125312472890. PMC 3805457. PMID 24167687.

- ↑ Hanekamp BB, Zijlstra JG, Tulleken JE, Ligtenberg JJ, van der Werf TS, Hofstra LS (2005). "Serotonin syndrome and rhabdomyolysis in venlafaxine poisoning: a case report" (PDF). The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 63 (8): 316–8. PMID 16186642. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Bymaster FP, Dreshfield-Ahmad LJ, Threlkeld PG, Shaw JL, Thompson L, Nelson DL, et al. (December 2001). "Comparative affinity of duloxetine and venlafaxine for serotonin and norepinephrine transporters in vitro and in vivo, human serotonin receptor subtypes, and other neuronal receptors". Neuropsychopharmacology. 25 (6): 871–80. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00298-6. PMID 11750180.

- ↑ Sabatucci JP, Mahaney PE, Leiter J, Johnston G, Burroughs K, Cosmi S, et al. (May 2010). "Heterocyclic cycloalkanol ethylamines as norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 20 (9): 2809–12. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.03.059. PMID 20378347.

- ↑ Bymaster, Frank P.; Dreshfield-Ahmad, Laura J.; Threlkeld, Penny G.; Shaw, Janice L.; Thompson, Linda; Nelson, David L.; Hemrick-Luecke, Susan K.; Wong, David T. (December 2001). "Comparative Affinity of Duloxetine and Venlafaxine for Serotonin and Norepinephrine Transporters in vitro and in vivo , Human Serotonin Receptor Subtypes, and Other Neuronal Receptors". Neuropsychopharmacology. 25 (6): 871–880. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00298-6. PMID 11750180. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Roth, Bryan L.; Kroeze, Wesley K. (2006). "Screening the receptorome yields validated molecular targets for drug discovery". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 12 (14): 1785–1795. doi:10.2174/138161206776873680. ISSN 1381-6128. PMID 16712488.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00001483 for "Acute Effectiveness of Additional Drugs to the Standard Treatment of Depression" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ Goeringer KE, McIntyre IM, Drummer OH (2001). "Postmortem tissue concentrations of venlafaxine". Forensic Science International. 121 (1–2): 70–5. doi:10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00455-8. PMID 11516890.

- ↑ Wellington K, Perry CM (2001). "Venlafaxine extended-release: a review of its use in the management of major depression". CNS Drugs. 15 (8): 643–69. doi:10.2165/00023210-200115080-00007. PMID 11524036.

- ↑ "Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology – Cambridge University Press". Stahlonline.cambridge.org. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ Delgado PL, Moreno FA (2000). "Role of norepinephrine in depression". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 61 (Suppl 1): 5–12. PMID 10703757.[full citation needed]

- ↑ Stern, Theodore A.; Fava, Maurizio; Wilens, Timothy E.; Rosenbaum, Jerrold F. (2015). Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 860. ISBN 9780323295079. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ The Opioid System as the Interface between the Brain's Cognitive and Motivational Systems. Academic Press. 2018. p. 73. ISBN 9780444641687. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Pae CU (December 2011). "Desvenlafaxine in the treatment of major depressive disorder". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 12 (18): 2923–8. doi:10.1517/14656566.2011.636033. PMID 22098230.

- ↑ Shams ME, Arneth B, Hiemke C, Dragicevic A, Müller MJ, Kaiser R, Lackner K, Härtter S (October 2006). "CYP2D6 polymorphism and clinical effect of the antidepressant venlafaxine". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 31 (5): 493–502. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2006.00763.x. PMID 16958828.

- ↑ Dean L (2015). "Venlafaxine Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520361. Bookshelf ID: NBK305561. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Parker G, Blennerhassett J (April 1998). "Withdrawal reactions associated with venlafaxine". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 32 (2): 291–4. doi:10.3109/00048679809062742. PMID 9588310.

- ↑ "Rs2032583 -SNPedia". Snpedia.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.[unreliable source?]

- ↑ Uhr M, Tontsch A, Namendorf C, Ripke S, Lucae S, Ising M, Dose T, Ebinger M, Rosenhagen M, Kohli M, Kloiber S, Salyakina D, Bettecken T, Specht M, Pütz B, Binder EB, Müller-Myhsok B, Holsboer F (2008). "Polymorphisms in the drug transporter gene ABCB1 predict antidepressant treatment response in depression". Neuron. 57 (2): 203–209. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.017. PMID 18215618.

- ↑ Whyte IM, Dawson AH, Buckley NA (May 2003). "Relative toxicity of venlafaxine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in overdose compared to tricyclic antidepressants" (PDF). QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians. 96 (5): 369–74. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcg062. PMID 12702786.

- ↑ DeVane CL (2003). "Immediate-release versus controlled-release formulations: pharmacokinetics of newer antidepressants in relation to nausea". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (Suppl 18): 14–9. PMID 14700450.

- ↑ Staton, Tracy (13 June 2012). "Drugstores accuse Pfizer, Teva of blocking Effexor generics". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

Further reading[edit | edit source]

- Dean L (July 2015). "Venlafaxine Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520361. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

External links[edit | edit source]

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- "Venlafaxine (marketed as Effexor) Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 10 July 2015. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)