In music, a sketch is an informal document prepared by a composer to assist in the process of composition.

Sketches may range greatly in scope and detail, from the smallest snippets to full drafts; concerning Ludwig van Beethoven's sketchbooks, for instance, Dean writes that they "include every imaginable state between unaccompanied melodic motifs of a few notes to thoroughly worked-out full scores; even his fair copies of essentially 'finished' works show the signs of continuing composition."[1]

Whether a composer's sketches survive past his or her lifetime depends particular on the composer's own practice and partly on posterity's. Some composers habitually discarded their sketches when a composition was completed (for instance, Johannes Brahms),[2] while others kept their sketches; sometimes in great numbers, as in the case of Beethoven. Mozart kept a great many sketches, but some were given away to friends as keepsakes following his death, and lost.[citation needed]

Why composers sketch[edit]

One reason for sketches is the fallibility of human memory. But there are more sophisticated reasons to sketch: most of classical music arranges the themes of each movement into a substantial architecture, for instance involving sonata form. The eighteenth century theorists H. C. Koch and J. G. Sulzer, in their written advice to composers, suggested that they should prepare sketches that would lay out how the various themes of the work would be arranged to create the overall structure.[2] Marston adds that Koch and Sulzer's recommendations "do in fact accord well with what scholars, borrowing from the terminology developed in relation to Beethoven's sketches, call a 'continuity draft', a notational form in which [for example] 'Beethoven can be seen fitting together the more fragmentary ideas made earlier into a coherent whole' (Cooper, 1990, p. 105)."[3]

Reasons to study sketches[edit]

Since the mid-19th century, the study of composers' sketches has been a branch of musicology. Nicholas Marston, writing in the New Grove, lists three reasons why the study of sketches can be of interest.

- The history of how a work was created serves as data for biographical accounts of composers; for instance, it can tell us whether a composition was the product of years of work or quickly achieved.

- Sketches are occasionally used by composers in attempts to write convincing completions of works left unfinished by other composers at their deaths.[4]

- Above all, there is the interest, widely shared among devotees of music, in how compositions were created; as the Oxford Dictionary of Music says, sketches are "of great fascination to musical scholars as showing the workings of a composer's mind."[5] This holds both for the general question of how composition takes place, but also at the level of individual works: scholars are interested (Marston) in "the 'biography' of the composition, as it were, rather than of the composer". He adds a caveat: "it should be obvious that 'compositional process' denotes a spectrum of activities far too complex to be equated simply with the writing of sketches."

A fourth possibility is also mentioned by Marston, namely that one might appeal to the sketches to support a particular formal analysis (i.e. in music theory) of a finished work. This practice is controversial.[2]

By composer[edit]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2017) |

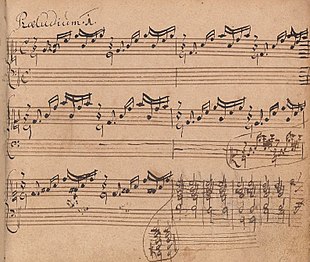

J. S. Bach[edit]

Surviving sketches by Johann Sebastian Bach include:[6][7]

- O Traurigkeit, o herzeleid, BWV Anh. 200: sketch (fragment) of a chorale prelude in the Orgelbüchlein manuscript

- BWV Anh. 2: outline of a cantata for Trinity XIX (6 bars)[8]

- BWV 149/1a: instrumental opening movement of a cantata, breaking off after the first word with which the singers enter ("Man..."), and thus seen as an alternative abandoned draft of the only Bach cantata that opens with that word (Man singet mit Freuden vom Sieg, BWV 149)

- BWV 1059, fragment of nine bars of a harpsichord concerto (arranged from the opening sinfonia, for organ and orchestra, of the cantata Geist und Seele wird verwirret, BWV 35)

The Klavierbüchlein für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach contains, among several comparable early versions of compositions that became better known in their later versions, a sketch of what evolved into the first prelude of The Well-Tempered Clavier.[6][7]

Mozart[edit]

The body of sketches by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is very substantial. The watermark studies of Alan Tyson yielded among other results the conclusion that Mozart would sometimes leave a work only partially complete (in sketch form) for a number of years, then finish it when an opportunity for performance arose.[9] This in turn has been taken to support the view that Mozart carefully retained his sketches simply as a good business practice, keeping open the possibility of future performances and publication for works not immediately promising in this respect.[10]

Beethoven[edit]

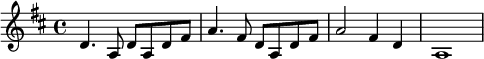

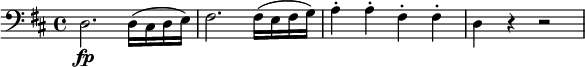

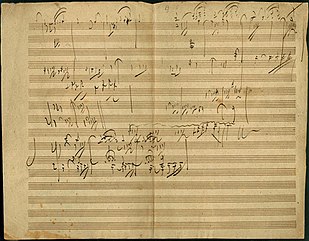

The corpus of Beethoven's surviving sketches is substantial[2] and frequently illustrates Beethoven's method of work, which was often slow and arduous. Commentary on Beethoven's finished works sometimes point to the extremely primitive or unpromising character of the themes as they first appear. For instance, Antony Hopkins pointed out the following sketch material for the Second Symphony, remarking that it "bears more resemblance to a bugle-call than a symphony."

He added, "One wonders why he bothered to commit such banalities to paper at all but it seems to have been an essential part of his creative procedure."[11] Hopkins's discussion (pp. 38–39) covers two further sketches, shown below:

These can be seen to be gradually evolving toward the actual main theme of the first movement as it appears in the symphony:

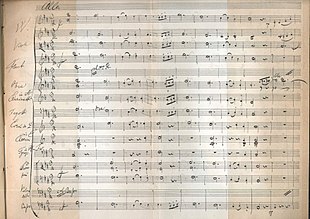

Schubert[edit]

Sketches by Franz Schubert include the abandoned third movement of his Unfinished Symphony, and the fragment known as Piano Sonata in E minor, D 769A.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

Among Schubert's symphonies there are several sketches for a symphony in D major. In the first edition of the Deutsch catalogue, these were grouped under D 615, apart from the early D 997. Apart from the completed Third Symphony, D 200, there appear to be at least four independent sets of sketches for a symphonic work in that key:[12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

- Symphony in D major, D. 2B, formerly D 997 (1811?): fragment of the first movement is extant

- Symphony in D major, D 615 (1818): piano sketches of two movements are extant

- Symphony in D major, D 708A (after 1820): piano sketches of all four movements are extant

- Symphony in D major, D 936A, known as Symphony No. 10 (1828?): piano sketches of all three movements are extant

Also the four movements of his Seventh Symphony, D 729, in E major (1821), only survive as sketches.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

Schubert's unfinished piano music ranges from rejected sketches of a few bars (e.g. D 309A) to fairly elaborate drafts with several complete movements (e.g. Reliquie sonata). The sonata D 568 exists in two stages of development: the unfinished draft version in D-flat major, and the four-movement E-flat major version which Schubert prepared for publication near the end of his life.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

Also in other genres Schubert produced sketches and drafts, some abandoned, and some later developed into complete compositions:[12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25]

- One of Schubert's earliest compositions, the song D 1A, survives as a draft without text.

- "Das war ich", D deest (1816, formerly grouped with D 174): one of Schubert's shortest sketches, a melody line he may have considered for setting a text by Theodor Körner, that is, the text of D 174

- Schubert composed three string trios, the first two of these only extant as abandoned sketches (D 111A and 471), the third, D 581, existing in a draft and a final version.

- Schubert's stage works include several unfinished works that were at least half completed, such as Lazarus, Sakuntala and Der Graf von Gleichen, as well as sketches that were abandoned after a few incomplete numbers (e.g. Rüdiger and D 982).

References[edit]

- ^ Jeffrey Dean (n.d.) "Sketch", in The Oxford Companion to Music, online edition, oxfordmusiconline.com, downloaded 10 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d Marston n.d.

- ^ Marston n.d.. Marston cited Barry Cooper's book Beethoven and the Creative Process (Oxford, 1990).

- ^ For examples see Requiem (Mozart), Symphony No. 10 (Beethoven/Cooper), Symphony No. 10 (Schubert), Symphony No. 10 (Mahler), and Symphony No. 3 (Elgar/Payne).

- ^ Online edition, article "Sketch", at oxfordmusiconline.com, (downloaded 10 November 2017).

- ^ a b Schmieder, Dürr, and Kobayashi 1998.

- ^ a b BD website.

- ^ Work 01309 at Bach Digital website

- ^ Alan Tyson (1987) Mozart: Studies of the Autograph Scores. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1987.

- ^ Konrad, Ulrich (2006) "Compositional method", in Cliff Eisen and Simon P. Keefe, The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Antony Hopkins (1981) The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. London: Heineman, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b c d e Badura-Skoda & Branscombe 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Deutsch 1951.

- ^ a b c d e Deutsch 1978.

- ^ a b c d e Hilmar & Jestremski 2004.

- ^ a b c d e Kube 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Newbould 1999.

- ^ a b c d e Reed 1997.

- ^ a b c d e van Hoorickx 1971.

- ^ a b c d e van Hoorickx 1974–1976.

- ^ a b c d e AGA 1884–1897.

- ^ a b c d e NSA scores.

- ^ a b c d e NSA II, 15.

- ^ a b c d e NSA website.

- ^ a b c d e Schubert-online.

Sources[edit]

by author[edit]

- Badura-Skoda, Eva; Branscombe, Peter, eds. (2008). Schubert Studies: Problems of Style and Chronology. Contributions by Walther Dürr ("Schubert's Songs and Their Poetry", pp. 1–24), Rufus Hallmark ("Schubert's 'Auf dem Strom'", pp. 25–46), Elaine Brody ("Schubert and Sulzer Revisited", pp. 47–60), Marius Flothuis ("Schubert Revises Schubert", pp. 61–84), Elizabeth Norman McKay ("Schubert as Composer of Operas", pp. 85–104), Peter Branscombe ("Schubert and the Melodrama", pp. 105–142), Christoph Wolff ("Schubert's 'Der Tod und dad Mädchen'", pp. 143–172), Peter Gülke (on String Quintet D 956, pp. 173–186), Paul Badura-Skoda (on Schubert's 'Great' C major Symphony, pp. 187–208), Robert Winter ("Paper Studies and the Future of Schubert Research", pp. 209–276), Eva Badura-Skoda ("The Chronology of Schubert's Piano Trios", pp. 277–296), Reinhard van Hoorickx ("The Chronology of Schubert's Fragments and Sketches", pp. 297–326), Arnold Feil ("Rhythm in Schubert", pp. 327–346) and Alexander Weinmann (on Leopold Puschl and Schubert's sojourn in Zseliz, pp. 347–356). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521088725.

- Deutsch, Otto Erich; et al. (Donald R. Wakeling) (1951). Schubert: Thematic Catalogue of all his Works in Chronological Order (1st ed.). London: Dent; 1995 reprint, with errata correction, by Dover Publications: The Schubert Thematic Catalogue. ISBN 0486286851

{{cite book}}: External link in|postscript= - Deutsch, Otto Erich; et al. (Walther Dürr, Arnold Feil, Christa Landon and Werner Aderhold) (1978). Franz Schubert: Thematisches Verzeichnis seiner Werke in chronologischer Folge. New Schubert Edition (in German). Vol. Series VIII (Supplement), Vol. 4. Kassel: Bärenreiter. ISBN 9783761805718. ISMN 9790006305148.

{{cite book}}: External link in|volume= - Hilmar, Ernst; Jestremski, Margret, eds. (2004). Schubert-Enzyklopädie (in German). Vol. 1. Introduction by Alfred Brendel. Tutzing: Hans Schneider. ISBN 3795211557.+[de]&rft.date=2004&rft.isbn=3795211557&rft_id=https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schubert-Enzyklop%C3%A4die.jpg&rfr_id=info:sid/en.wikipedia.org:Sketch+(music)" class="Z3988">

- Kube, Michael (2009). "Franz Schuberts Deutsche Trauermesse (D 621) als Problem der Text- und Stilkritik". In Mitterauer, Gertraud; Müller, Ulrich; Springeth, Margarete; Vitzthum, Verena (eds.). Was ist Textkritik?: Zur Geschichte und Relevanz eines Zentralbegriffs der Editionswissenschaft (in German). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 129–140. ISBN 978-3484970786.

- Marston, Nicholas (n.d.). "Sketch". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

- Newbould, Brian (1999). Schubert: The Music and the Man. University of California Press. ISBN 0520219570.

- Reed, John (1997). The Schubert Song Companion. Manchester University Press. ISBN 1901341003.

- Schmieder, Wolfgang, Alfred Dürr, and Yoshitake Kobayashi (eds.). 1998. Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis: Kleine Ausgabe (BWV2a). Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel. ISBN 978-3765102493.(in German)

- van Hoorickx, Reinhard (1971). "Franz Schubert (1797–1828) List of the Dances in Chronological Order". Revue belge de Musicologie / Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Muziekwetenschap. Belgian Musicological Society. 25 (1): 68–97. doi:10.2307/3686180. ISSN 0771-6788. JSTOR 3686180.

- van Hoorickx, Reinhard (1974–1976). "Thematic Catalogue of Schubert's Works: New Additions, Corrections and Notes". Revue belge de Musicologie / Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Muziekwetenschap. Belgian Musicological Society. 28–30: 136–171. doi:10.2307/3686053. ISSN 0771-6788. JSTOR 3686053.

Collective editions[edit]

- Alte Gesamt-Ausgabe (AGA) = Franz Schubert's Works: Schubert, Franz (1884–1897). [multiple volumes: 21 series + critical report]. Franz Schubert's Werke: Kritisch durchgesehene Gesammtausgabe (in German). Edited by Johannes Brahms, Ignaz Brüll, Anton Door, Julius Epstein, Johann Nepomuk Fuchs, Josef Gänsbacher, Joseph Hellmesberger Sr. and Eusebius Mandyczewski. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel. Reprints of several volumes by Kalmus and Dover Publications; Franz Schubert's Werke (Series I–XIX and XXI), Series XX, Revisionsbericht: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Bach Digital (BD) website: "Bach Digital". Leipzig Bach Archive, the Saxon State and University Library Dresden (Sächsische Landesbibliothek – Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Dresden = SLUB), SBB and Leipzig University. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- Neue Schubert-Ausgabe (NSA) = New Schubert Edition:

- NSA scores: Schubert, Franz (1968–2017). [over 80 volumes in eight series]. Franz Schubert (1797–1828): New Edition of the Complete Works (in German). Edited by International Schubert Association (Tübingen). Kassel: Bärenreiter; Individual volumes:

{{cite book}}: External link in|series=- NSA II, 15: Schubert, Franz; Neumann, Johann Philipp (2008). Jahrmärker, Manuela; Aigner, Thomas (eds.). Sacontala. New Schubert Edition (in German). Vol. Series II (Stage Works), Vol. 15. Kassel: Bärenreiter. ISMN 9790006497294.

{{cite book}}: External link in|volume= - NSA VIII, 4: See above Deutsch (1978)

- NSA II, 15: Schubert, Franz; Neumann, Johann Philipp (2008). Jahrmärker, Manuela; Aigner, Thomas (eds.). Sacontala. New Schubert Edition (in German). Vol. Series II (Stage Works), Vol. 15. Kassel: Bärenreiter. ISMN 9790006497294.

- NSA website: "New Schubert Edition". Tübingen: International Schubert Association. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- NSA scores: Schubert, Franz (1968–2017). [over 80 volumes in eight series]. Franz Schubert (1797–1828): New Edition of the Complete Works (in German). Edited by International Schubert Association (Tübingen). Kassel: Bärenreiter; Individual volumes:

- Schubert Online: "www.schubert-online.at: Schubert music manuscripts, first and early editions online". Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW). Retrieved 1 September 2017.

Further reading[edit]

- Keefe, Simon P., ed. (2006). Mozart Studies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521851025.