- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Infraclass: Marsupialia

- Order: Dasyuromorphia

- Family: †Thylacinidae

- Genus: †Thylacinus

- Species: †T. cynocephalus

Thylacinus cynocephalus

| Tasmanian tiger |

|---|

|

| Scientific Classification |

|

| Binomial |

Thylacinus cynocephalus |

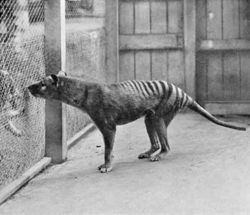

The Tasmanian tiger or Thylacine was a large carnivorous marsupial native to Australia which is thought to have become extinct in the 20th century. It is known by the scientific name Thylacinus cynocephalus also by the common names Tasmanian Wolf, Marsupial Wolf, and colloquially the Tassie (or Tazzy) Tiger or simply the Tiger.

The Thylacine was extinct on the Australian mainland thousands of years before European settlement of the continent, but survived on the island of Tasmania along with a number of other endemic species such as the Tasmanian Devil. Heavy hunting is generally blamed for its extinction, but other contributory factors may have been disease, the introduction of dogs, and human encroachment into its habitat. Despite being officially classified as extinct, sightings are still reported.

The Thylacinidae were created on the sixth day of creation, along with other land-dwelling creatures. It was of the created kind Thylacinidae which had over 14 species within it, all of which developed their variety after the flood. After leaving the Ararat region, the Thylacine along with the majority of other marsupials, crossed into New Guinea from South-east Asia, and afterwards, eventually crossed over the land bridge that once connected New Guinea to Australia. There have been many fossils of Marsupials on every continent, along with the living North American Marsupial, the opposum.

First contact with the Thylacine was made by the indigenous peoples of Australia. Numerous examples of Thylacine engravings and rock art have been found dating back to at least 1000 BC. Petroglyph images of the Thylacine can be found at the Dampier Rock Art Precinct on the Burrup Peninsula in Western Australia. By the time the first explorers arrived, the animal was already rare in Tasmania. It may have been encountered by Europeans as far back as 1642 when Abel Tasman first arrived in Tasmania. His shore party reported seeing the footprints of "wild beasts having claws like a "Tyger". "A short relation out of the journal of Captain Abel Jansen Tasman, upon the discovery of the South Terra incognita; not long since published in the Low Dutch". Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne, arriving with the Mascarin in 1772, reported seeing a "tiger cat". "Crozet's Voyage to Tasmania, New Zealand, etc....1771–1772.". London. Truslove and Shirley. Positive identification of the Thylacine as the animal encountered cannot be made from this report since the Tiger Quoll (Dasyurus maculatus) is similarly described. The first definitive encounter was by French explorers on 13 May 1792, as noted by the naturalist Jacques Labillardière, in his journal from the expedition led by D'Entrecasteaux. However, it was not until 1805 that William Paterson, the Lieutenant Governor of Tasmania, sent a detailed description for publication in the Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. The first detailed scientific description was made by Tasmania's Deputy Surveyor-General, George Harris in 1808, five years after first settlement of the island.

Harris originally placed the Thylacine in the genus Didelphis, which had been created by Linnaeus for the American opossums, describing it as Didelphis cynocephala, the "dog-headed opossum". Recognition that the Australian marsupials were fundamentally different from the known mammal genera led to the establishment of the modern classification scheme, and in 1796 Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire created the genus Dasyurus where he placed the Thylacine in 1810. To resolve the mixture of Greek and Latin nomenclature the species name was altered to cynocephalus. In 1824 it was separated out into its own genus, Thylacinus, by Temminck. The common name derives directly from the genus name, originally from the Greek θύλακος (thylakos), meaning pouch or sack.

The Thylacine resembled a large, short-haired dog with a stiff tail, which smoothly extended from the body like that of a kangaroo. It was about 100 to 130 cm long including its tail of about 50 to 65 cm, and had a very large gape. It was a yellowish-brown in colour with sixteen to eighteen dark stripes on its back and rump, hence its common name: "Tasmanian Tiger." The Thylacine's pouch opened to the rear of its body. In at least two male specimens a scrotal pouch, unique amongst marsupials, was also documented.

One unusual feature of the Thylacine was the ability to open its jaws to a surprising extent. Although it is most unlikely that the gape was as wide as some reports have stated (~180°), it was still the widest of any known mammal. This capability is captured in part of a short black-and-white film sequence dating from 1936 which shows a captive Thylacine in a zoo.

The Thylacine is likely to have become extinct in mainland Australia about 2,000 years ago (possibly earlier in New Guinea). The extinction is attributed to competition from indigenous humans and invasive Dingos. Doubts exist over the impact of the Dingo, however, as the two species would not have been in direct competition with one another. The Dingo is a primarily diurnal predator, while it is thought the Thylacine hunted mostly at night. In addition, the Thylacine had a more powerful build, which would have given it an advantage in one-to-one encounters.

Rock paintings from the Kakadu National Park clearly show that Thylacines were hunted by humans, and it is believed that Dingos and Thylacines may have competed for the same prey. Their environments clearly overlapped: Thylacine sub-fossil remains have been discovered in proximity to those of Dingos. The adoption of the Dingo as a hunting companion by the indigenous peoples would have put the Thylacine under increased pressure.

Although long extinct on the Australian mainland by the time the European settlers arrived, the Thylacine survived into the 1930s in Tasmania, where there were no Dingos. At the time of the first settlement, the heaviest distributions were in the north-east, north-west and north-midland regions. From the early days of European settlement they were rarely sighted, but slowly began to be credited with numerous attacks on sheep; this led to the establishment of bounty schemes in an attempt to control their numbers. The Van Dieman's Land Company introduced bounties on the Thylacine from as early as 1830 and between 1888 and 1909 the Tasmanian government paid £1 a head for the animal (10 shillings for pups). In all they paid out 2,184 bounties, but it is thought that many more Thylacines were killed than were claimed for. Its extinction is popularly attributed to these relentless efforts by farmers and bounty hunters. However, it is likely that multiple factors led to its decline and eventual extinction, including competition with wild dogs (introduced by settlers), erosion of habitat, the concurrent extinction of prey species, and a distemper-like disease that also affected many captive specimens at the time.

Whatever the reason, the animal had become extremely rare in the wild by the late 1920s. There were several efforts to save the species from extinction. Records of the Wilsons Promontory management committee dating to 1908 included recommendations for Thylacines to be reintroduced to several suitable locations on the Victorian mainland. In 1928, the Tasmanian Advisory Committee for Native Fauna had recommended a reserve to protect any remaining Thylacines, with potential sites of suitable habitat including the Arthur-Pieman area of western Tasmania.

The last known wild Thylacine to be killed was shot in 1930, by farmer Wilf Batty in Mawbanna, in the North East of the state. The animal (believed to be a male) had been seen round Batty's hen houses for several weeks.

The last Thylacine, later referred to as Benjamin (although its gender has never been confirmed) was captured in 1933 and sent to the Hobart Zoo where it lived for three years. It died on 7 September 1936 (now known as National Threatened Species Day in Australia).[45] It is believed to have died as the result of neglect — locked out of its sheltered sleeping quarters, it was exposed to a rare occurrence of extreme Tasmanian weather: baking heat in the day and freezing temperatures at night. The last known motion picture footage taken of a living thylacine, 62 seconds of black-and-white footage of Benjamin pacing backwards and forwards in its enclosure, was taken in 1933.

Although there had been a conservation movement pressing for the Thylacine's protection since 1901, driven in part by the increasing difficulty in obtaining specimens for overseas collections, political difficulties prevented any form of protection coming into force until 1936. Official protection of the species by the Tasmanian government was introduced on July 10, 1936, 59 days before the last known specimen died in captivity.

The results of subsequent searches indicated a strong possibility of the survival of the species in Tasmania into the 1960s. Searches by Dr. Eric Guiler and David Fleay in the north-west of Tasmania found footprints and scats that may have belonged to the animal, heard vocalisations matching the description of those of the Thylacine, and collected anecdotal evidence from people reported to have sighted the animal. Despite the searches, no conclusive evidence was found to point to its continued existence in the wild.

The Thylacine held the status of "endangered species" until 1986. International standards state that any animal for which no specimens have been recorded for 50 years is to be declared extinct. Since no definitive proof of the Thylacine's existence had been found since Benjamin died in 1936, it now met that official criterion and was declared officially extinct by the IUCN. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is more cautious, listing it as "possibly extinct"

|

||||||||||||||||||||