| Psychology |

| History |

| Psychologists |

| Divisions |

|---|

| Abnormal |

| Applied |

| Biological |

| Clinical |

| Cognitive |

| Comparative |

| Developmental |

| Differential |

| Industrial |

| Parapsychology |

| Personality |

| Positive |

| Religion |

| Social |

| Approaches |

| Behaviorism |

| Depth |

| Experimental |

| Gestalt |

| Humanistic |

| Information processing |

Social psychology is a branch of psychology that studies cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes of individuals as influenced by their group membership and interactions, and other factors that affect social life, such as social status, role, and social class. Social psychology examines the effects of social contacts on the development of attitudes, stereotypes, and so forth.

A relatively recent field, social psychology has nonetheless had a significant impact not only on the academic worlds of psychology, sociology, and the social sciences in general, but has also affect public understanding and expectation of human social behavior. By studying how people behave under extreme social influences, or lack thereof, great advances have been made in understanding human nature. Human beings are essentially social beings, and thus, social interaction is vital to the health of each person. Through investigating the factors that affect social life and how social interactions affect individual psychological development and mental health, a greater understanding of how humankind as a whole can live together in harmony is emerging.

History

The discipline of social psychology began in the United States at the dawn of the twentieth century. The first published study in this area was an experiment by Norman Triplett (1898) on the phenomenon of social facilitation. During the 1930s, many Gestalt psychologists, particularly Kurt Lewin, fled to the United States from Nazi Germany. They were instrumental in developing the field as something separate from the behavioral and psychoanalytic schools that were dominant during that time, and social psychology has always maintained the legacy of their interests in perception and cognition. Attitudes and a variety of small group phenomena were the most commonly studied topics in this era.

During World War II, social psychologists studied persuasion and propaganda for the U.S. military. After the war, researchers became interested in a variety of social problems, including gender issues and racial prejudice. In the sixties, there was growing interest in a variety of new topics, such as cognitive dissonance, bystander intervention, and aggression. By the 1970s, however, social psychology in America had reached a crisis. There was heated debate over the ethics of laboratory experimentation, whether or not attitudes really predicted behavior, and how much science could be done in a cultural context (Kenneth Gergen, 1973). This was also the time when a radical situationist approach challenged the relevance of self and personality in psychology.

During the years immediately following World War II, there was frequent collaboration between psychologists and sociologists (Sewell, 1989). However, the two disciplines have become increasingly specialized and isolated from each other in recent years, with sociologists focusing on macro variables (such as social structure) to a much greater extent. Nevertheless, sociological approaches to social psychology remain an important counterpart to psychological research in this area.

Michael Argyle pioneered social psychology as an academic field in Britain. In 1952, when he was appointed the first lecturer in social psychology at the University of Oxford, the field was no more than embryonic (Robinson 2002). In fact, only Oxford and the London School of Economics had departments of social psychology at the time. In his research, which attracted visits from many American social psychologists, Argyle maintained a different approach, one that emphasized more real world problems and solutions over laboratory-style investigations, but always without sacrificing the integrity of the experimental method. In addition to his research and many publications, of which Psychology of Interpersonal Behaviour published in 1967 became a best-seller, he gave lectures and seminars to academics, professionals, and the wider public so that social psychology became known both as a scientific enterprise and as a necessary perspective for solving social problems.

Social psychology reached maturity in both theory and method during the 1980s and 1990s. Careful ethical standards regulated research, and greater pluralism and multicultural perspectives emerged. Modern researchers are interested in a variety of phenomena, but attribution, social cognition, and self-concept are perhaps the greatest areas of growth. Social psychologists have also maintained their applied interests, with contributions in health and environmental psychology, as well as the psychology of the legal system.

Social psychology is the study of how social conditions affect human beings. Scholars in this field today are generally either psychologists or sociologists, though all social psychologists employ both the individual and the group as their units of analysis. Despite their similarity, the disciplines tend to differ in their respective goals, approaches, methods, and terminology. They also favor separate academic journals and professional societies.

Fields of social psychology

Social psychology is the scientific study of how people's thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the actual, imagined, or implied presence of others (Allport, 1985). By this definition, scientific refers to the empirical method of investigation. The terms thoughts, feelings, and behaviors include all of the psychological variables that are measurable in a human being. The statement that others may be imagined or implied suggests that we are prone to social influence even when no other people are present, such as when watching television, or following internalized cultural norms.

Social psychology bridges the interest of psychology (with its emphasis on the individual) with sociology (with its emphasis on social structures). Psychologically oriented researchers place a great deal of emphasis on the immediate social situation, and the interaction between person and situation variables. Their research tends to be highly empirical and is often centered around laboratory experiments. Psychologists who study social psychology are interested in such topics as attitudes, social cognition, cognitive dissonance, social influence, and interpersonal behavior. Two influential journals for the publication of research in this area are The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, and The Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

Attitudes

The study of attitudes is a core topic in social psychology. Attitudes are involved in virtually every other area of social psychology, including conformity, interpersonal attraction, social perception, and prejudice. In social psychology, attitudes are defined as learned evaluations of a person, object, place, or issue that influence thought and action (Perloff, 2003). Put more simply, attitudes are basic expressions of approval or disapproval, favorability or unfavorability, or as Bem (1970) put it, likes and dislikes. Examples would include liking chocolate ice cream, being anti-abortion, or endorsing the values of a particular political party.

Social psychologists have studied attitude formation, the structure of attitudes, attitude change, the function of attitudes, and the relationship between attitudes and behavior. Because people are influenced by the situation, general attitudes are not always good predictors of specific behavior. For a variety of reasons, a person may value the environment and not recycle a can on a particular day. Attitudes that are well remembered and central to a self-concept, however, are more likely to lead to behavior, and measures of general attitudes do predict patterns of behavior over time.

Persuasion

The topic of persuasion has received a great deal of attention. Persuasion is an active method of influence that attempts to guide people toward the adoption of an attitude, idea, or behavior by rational or emotive means. Persuasion relies on appeals rather than strong pressure or coercion. Numerous variables have been found to influence the persuasion process, and these are normally presented in four major categories: Who said what to whom and how.

- The Communicator, including credibility, expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness

- The Message, including varying degrees of reason, emotion (such as fear), one-sided or two sided arguments, and other types of informational content

- The Audience, including a variety of demographics, personality traits, and preferences

- The Channel, including the printed word, radio, television, the internet, or face-to-face interactions

Dual process theories of persuasion (such as the Elaboration Likelihood Model) maintain that the persuasive process is mediated by two separate routes. Persuasion can be accomplished by either superficial aspects of the communication or the internal logic of the message. Whether someone is persuaded by a popular celebrity or factual arguments are largely determined by the ability and motivation of the audience. However, decades of research have demonstrated that deeply held attitudes are remarkably resistant to persuasion under normal circumstances.

Social cognition

Social cognition is a growing area of social psychology that studies how people perceive, think about, and remember information about others. One assumption in social cognition is that reality is too complex to easily discern, and so people see the world according to simplified schemas, or images of reality. Schemas are generalized mental representations that organize knowledge and guide information processing. For example, one's schema for mice might include the expectation that they are small, and furry, and eat cheese.

Schemas often operate automatically and unintentionally, and can lead to biases in perception and memory. Schematic expectations may lead people to see something that is not there. One experiment found that white American policemen are more likely to misperceive a weapon in the hands of a black man than a white man (Correll, et al., 2002). This type of schema is actually a stereotype, a generalized set of beliefs about a particular group of people. Stereotypes are often related to negative or preferential attitudes (prejudice) and behavior (discrimination). Schemas for types of events (such as doing laundry) are known as "scripts."

Another major concept in social cognition is attribution. Attributions are the explanations humans make for people's behavior, either one's own behavior or the behavior of others. An attribution can be either internal or external. Internal or dispositional attributions assign causality to factors within the person, such as ability or personality. External or situational attributions assign causality to an outside factor, such as the weather. Numerous biases in the attribution process have been discovered:

- Fundamental attribution error—the tendency to make dispositional attributions for behavior. The actor-observer effect is a refinement of this bias, the tendency to make dispositional attributions for other people's behavior and situational attributions for our own.

- Just world effect—the tendency to blame victims (a dispositional attribution) for their suffering. This is believed to be motivated by people's anxiety that good people, including themselves, could be victimized in an unjust world.

- Self-serving bias—the tendency to take credit for successes, and blame others for failure. Researchers have found that depressed individuals often lack this bias and actually have more realistic perceptions of reality.

Heuristics are cognitive short cuts. Instead of weighing all the evidence when making a decision, people rely on heuristics to save time and energy. The availability heuristic is used when people estimate the probability of an outcome based on how easy that outcome is to imagine. As such, vivid or highly memorable possibilities will be perceived as more likely than those that are harder to picture or are difficult to understand, resulting in a corresponding cognitive bias.

There are a number of other biases that have been found by social cognition researchers. The hindsight bias is a false memory of having predicted events, or an exaggeration of actual predictions, after becoming aware of the outcome. The confirmation bias is a type of bias leading to the tendency to search for, or interpret information in a way that confirms one's preconceptions.

Self-concept

The fields of social psychology and personality have merged over the years, and social psychologists have developed an interest in a variety of self-related phenomena. In contrast with traditional personality theory, however, social psychologists place a greater emphasis on cognitions than on traits. Much research focuses on the self-concept, which is a person's understanding of his or her self. The self-concept can be divided into a cognitive component, known as the self-schema, and an evaluative component, the self-esteem. The need to maintain a healthy self-esteem is recognized as a central human motivation in the field of social psychology. Self-efficacy beliefs are an aspect of the self-schema. Self-efficacy refers to an individual's expectation that performance on some task will be effective and successful.

People develop their self-concepts by a variety of means, including introspection, feedback from others, self-perception, and social comparison. By comparison to relevant others, people gain information about themselves, and they make inferences that are relevant to self-esteem. Social comparisons can be either upward or downward, that is, comparisons to people who are either higher in status or ability, or lower in status or ability. Downward comparisons are often made in order to elevate self-esteem.

Self-perception is a specialized form of attribution that involves making inferences about oneself after observing one's own behavior. Psychologists have found that too many extrinsic rewards (such as money) tend to reduce intrinsic motivation through the self-perception process. People's attention is directed to the reward and they lose interest in the task when the reward is no longer offered. This is an important exception to reinforcement theory.

Cognitive dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is a feeling of unpleasant arousal caused by noticing an inconsistency among one's cognitions (Festinger, 1957). Cognitive dissonance was originally developed as a theory of attitude change, but it is now considered to be a self theory by most social psychologists. Dissonance is strongest when a discrepancy has been noticed between one's self-concept and one's behavior; for example, doing something that makes one ashamed. This can result in self-justification as the individual attempts to deal with the threat. Cognitive dissonance typically leads to a change in attitude, a change in behavior, a self-affirmation, or a rationalization of the behavior.

An example of cognitive dissonance is smoking. Smoking cigarettes increases the risk of cancer, which is threatening to the self-concept of the individual who smokes. Most people believe themselves to be intelligent and rational, and the idea of doing something foolish and self-destructive causes dissonance. To reduce this uncomfortable tension, smokers tend to make excuses for themselves, such as "I'm going to die anyway, so it doesn't matter."

Social influence

Social influence refers to the way people affect the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of others. Like the study of attitudes, it is a traditional, core topic in social psychology. In fact, research on social influence overlaps considerably with research on attitudes and persuasion. Social influence is also closely related to the study of group dynamics, as most of the principles of influence are strongest when they take place in social groups.

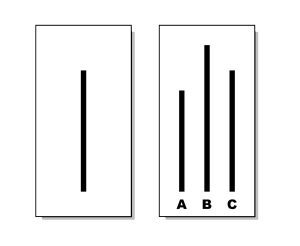

Conformity is the most common and pervasive form of social influence. It is generally defined as the tendency to act or think like other members of a group. Solomon Asch developed the paradigm for measuring conformity in the 1950s. In his groundbreaking studies Asch (1955) found that a surprisingly large number of people would conform to the majority opinion and give an obviously incorrect response to a simple visual task.

Group size, unanimity, cohesion, status, and prior commitment all help to determine the level of conformity in an individual. Conformity is usually viewed as a negative tendency in American culture, but a certain amount of conformity is not only necessary and normal, but probably essential for a community to function.

The two major motives in conformity are: 1) Normative influence, the tendency to conform in order to gain social acceptance, and avoid social rejection or conflict, as in peer pressure; and 2) informational influence, which is based on the desire to obtain useful information through conformity, and thereby achieve a correct or appropriate result. Minority influence is the degree to which a smaller faction within the group influences the group during decision making. Note that this refers to a minority position on some issue, not an ethnic minority. Their influence is primarily informational and depends on consistent adherence to a position, degree of defection from the majority, and the status and self-confidence of the minority members. Reactance is a tendency to assert oneself by doing the opposite of what is expected. This phenomenon is also known as anticonformity and it appears to be more common in men than in women.

There are two other major areas of social influence research. Compliance refers to any change in behavior that is due to a request or suggestion from another person. "The Foot-in-the-door technique" is a compliance method in which the persuader requests a small favor and then follows up with a larger favor; for example, asking for the time, and then asking for ten dollars. A related trick is the "bait and switch" (Cialdini, 2000). The third major form of social influence is obedience. This is a change in behavior that is the result of a direct order or command from another person.

A different kind of social influence is the "self-fulfilling prophecy." This is a prediction that, in being made, actually causes itself to become true. For example, in the stock market, if it is widely believed that a "stock market crash" is imminent, investors may lose confidence, sell most of their stock, and actually cause the crash. Likewise, people may expect hostility in others and actually induce this hostility by their own behavior.

Group dynamics

A social group consists of two or more people that interact, influence each other, and share a common identity. Groups have a number of emergent qualities:

- Norms are implicit rules and expectations for group members to follow, e.g. saying thank you and shaking hands.

- Roles are implicit rules and expectations for specific members within the group, such as the oldest sibling, who may have additional responsibilities in the family.

- Interpersonal relationships are patterns of liking within the group, and also differences in prestige or status, such as leaders or popular people.

Temporary groups and aggregates share few or none of these features, and do not qualify as true social groups. People waiting in line to get on a bus, for example, do not constitute a social group.

Groups are important not only because they offer social support, resources, and a feeling of belonging, but because they supplement an individual's self-concept. To a large extent, people define themselves by their group memberships. This natural tendency for people to identify themselves with a particular group and contrast themselves with other groups is known as social identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Unfortunately, social identity can lead to feelings of "us and them." It is frequently associated with preferential treatment toward the ingroup and prejudice and discrimination against outgroups.

Groups often moderate and improve decision making, and are frequently relied upon for these benefits, such as committees and juries. A number of group biases, however, can interfere with effective decision making. For example, "group polarization," formerly known as the "risky shift," occurs when people polarize their views in a more extreme direction after group discussion. Even worse is the phenomenon of "groupthink." This is a collective thinking defect that is characterized by a premature consensus. Groupthink is caused by a variety of factors, including isolation and a highly directive leader. Janis (1972) offered the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion as a historical case of groupthink.

Groups also affect performance and productivity. Social facilitation, for example, is a tendency to work harder and faster in the presence of others. Social facilitation increases the likelihood of the dominant response, which tends to improve performance on simple tasks and reduce it on complex tasks. In contrast, "social loafing" is the tendency of individuals to slack when working in a group. Social loafing is common when the task is considered unimportant and individual contributions are not easy to see.

Social psychologists study a variety of group related, or collective phenomena such as the behavior of crowds. An important concept in this area is deindividuation, a reduced state of self-awareness that can be caused by feelings of anonymity. Deindividuation is associated with uninhibited and sometimes dangerous behavior. It is common in crowds and mobs, but it can also be caused by a disguise, a uniform, alcohol, dark environments, or online anonymity.

Relations with others

Social psychologists are interested in the question of why people sometimes act in a prosocial way (helping, liking, or loving others), but at other times act in an antisocial way (hostility, aggression, or prejudice against others).

Aggression can be defined as any behavior that is intended to harm another human being. "Hostile" aggression is accompanied by strong emotions, particularly anger. Harming the other person is the goal. "Instrumental" aggression is only a means to an end. Harming the person is used to obtain some other goal, such as money. Research indicates that there are many causes of aggression, including biological factors like testosterone and environmental factors, such as social learning. Immediate situational factors, such as frustration, are also important in triggering an aggressive response.

Although violence is a fact of life, people are also capable of helping each other, even complete strangers, in emergencies. Research indicates that altruism occurs when a person feels empathy for another individual, even in the absence of other motives (Batson, 1998). However, according to the bystander effect, the probability of receiving help in an emergency situation drops as the number of bystanders increases. This is due to conformity effects and a diffusion of responsibility (Latane, 1981).

Interpersonal attraction

Another major area in the study of people's relations to each other is interpersonal attraction. This refers to all of the forces that lead people to like each other, establish relationships, and in some cases, fall in love. Several general principles have been discovered by researchers in this area:

- Proximity and, mainly, physical proximity increases attraction, as opposed to long distance relationships which are more at risk

- Familiarity is the mere exposure to others. It increases attraction, even when the exposure is not consciously realized

- Similarity means that two or more persons are similar in their attitudes, background, and other traits. The greater the similarity the more probable it id that they will like each other. Contrary to popular opinion, opposites do not usually attract.

Physical attractiveness is an important element of romantic relationships, particularly in the early stages which are characterized by high levels of passion. Later on, similarity becomes more important and the type of love people experience shifts from passionate to companionate. Robert Sternberg (1986) has suggested that there are three components to love: Intimacy, passion, and commitment.

According to social exchange theory, relationships are based on rational choice and cost-benefit analysis. If one partner's costs begin to outweigh his or her benefits, that person may leave the relationship, especially if there are good alternatives available. With time, long term relationships tend to become communal rather than simply based on exchange.

Interpersonal perception

Interpersonal perception examines the beliefs that interacting people have about each other. This area differs from social cognition and person perception by being interpersonal rather than intrapersonal. By requiring at least two real people to interact, research in this area examines phenomena such as:

- Accuracy—the correctness of A's beliefs about B

- Self-other agreement—whether A's beliefs about B matches B's beliefs about himself

- Similarity—whether A's and B's beliefs match

- Projection—whether A's beliefs about B match A's beliefs about herself

- Reciprocity—the similarity of A's and B's beliefs about each other

- Meta-accuracy—whether A knows how others see her

- Assumed projection—whether A thinks others see her as she sees them

These variables cannot be assessed in studies that ask people to form beliefs about fictitious targets.

Although interest in this area has grown rapidly with the publication of Malcolm Gladwell's 2005 book, Blink, and Nalini Ambady's "thin-slices" research (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1992), the discipline is still very young, having only been formally defined by David Kenny in 1994. The sparsity of research, in particular on the accuracy of first-impressions, means that social psychologists know a lot about what people think about others, but far less about whether they are right.

Many attribute this to a criticism that Cronbach wrote in 1955, about how impression accuracy was calculated, which resulted in a 30-year hiatus in research. During that time, psychologists focused on consensus (whether A and B agree in their beliefs about C) rather than accuracy, although Kenny (1994) has argued that consensus is neither necessary nor sufficient for accuracy.

Today, the use of correlations instead of discrepancy scores to measure accuracy (Funder, 1995) and the development of the Big Five model of personality have overcome Cronbach's criticisms and led to a wave of fascinating new research. For example, studies have found that people more accurately perceive Extraversion and Conscientiousness in strangers than they do the other personality domains (Watson, 1989); a five-second interaction tells as much as 15 minutes on these domains (Ambady & Rosenthal, 1992), and video tells more than audio alone (Borkenau & Liebler, 1992).

Links between social psychology and sociology

A significant number of social psychologists are sociologists. Their work has a greater focus on the behavior of the group, and thus examines such phenomena as interactions and social exchanges at the micro-level, and group dynamics and crowd psychology at the macro-level. Sociologists are interested in the individual, but primarily within the context of social structures and processes, such as social roles, race and class, and socialization. They tend to use both qualitative and quantitative research designs.

Sociologists in this area are interested in a variety of demographic, social, and cultural phenomena. Some of their major research areas are social inequality, group dynamics, social change, socialization, social identity, and symbolic interactionism.

Research methods in social psychology

Social psychologists typically explain human behavior as a result of the interaction of mental states and immediate, social situations. In Kurt Lewin's (1951) famous Heuristic, behavior can be viewed as a function of the person and the environment, B=f(P,E). In general, social psychologists have a preference for laboratory-based, empirical findings.

Social psychology is an empirical science that attempts to answer a variety of questions about human behavior by testing hypotheses, both in the laboratory and in the field. This approach to the field focuses on the individual, and attempts to explain how the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of individuals are influenced by other people. Careful attention to sampling, research design, and statistical analysis is important, and results are published in peer reviewed journals such as The Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, and The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

- Experimental methods involve the researcher altering a variable in the environment and measuring the effect on another variable. An example would be allowing two groups of children to play violent or nonviolent videogames, and then observing their subsequent level of aggression during free-play period. A valid experiment is controlled and uses random assignment.

- Correlational methods examine the statistical association between two naturally occurring variables. For example, one could correlate the amount of violent television children watch at home with the number of violent incidents the children participate in at school. Note that finding a correlation in such a study would not prove a causal relationship between violence on television and aggression in children. It is equally possible that aggressive children choose to watch more violent programs.

- Observational methods are purely descriptive and include naturalistic observation, contrived observation, participant observation, and archival analysis. These are less common in social psychology but are sometimes used when first investigating a phenomenon. An example would be to unobtrusively observe children on a playground (such as with a hidden video camera) and record the number and types of particular actions displayed.

Whenever possible, social psychologists rely on controlled experimentation. Controlled experiments require the manipulation of one or more independent variables in order to examine the effect on a dependent variable. Experiments are useful in social psychology because they are high in internal validity, meaning that they are free from the influence of confounding or extraneous variables, and so are more likely to accurately indicate a causal relationship. However, the small samples used in controlled experiments are typically low in external validity, or the degree to which the results can be generalized the larger population. There is usually a trade-off between experimental control (internal validity) and being able to generalize to the population (external validity).

Because it is usually impossible to test everyone, research tends to be conducted on a sample of persons from the wider population. Social psychologists frequently use survey research when they are interested in results that are high in external validity. Surveys use various forms of random sampling to obtain a sample of respondents that are representative of a population. This type of research is usually descriptive or correlational because there is no experimental control over variables. However, new statistical methods, like structural equation modeling, are being used to test for potential causal relationships in this type of data.

Regardless of which method is used, it is important to evaluate the research hypothesis in light of the results, either confirming or rejecting the original prediction. Social psychologists use statistics and probability testing to judge their results, which define a significant finding as less than 5 percent likely to be due to chance. Replications are important, to ensure that the result is valid and not due to chance, or some feature of a particular sample.

Ethics of sociopsychological research

The goal of social psychology is to understand cognition and behavior as they naturally occur in a social context, but the very act of observing people can influence and alter their behavior. For this reason, many social psychology experiments utilize deception to conceal or distort certain aspects of the study. Deception may include false cover stories, false participants (known as confederates or stooges), false feedback given to the participants, and so on.

The practice of deception has been challenged by some psychologists who maintain that deception under any circumstances is unethical, and that other research strategies (such as role-playing) should be used instead. Unfortunately, research has shown that role-playing studies do not produce the same results as deception studies and this has cast doubt on their validity. In addition to deception, experimenters have at times put people into potentially uncomfortable or embarrassing situations (for example the Milgram Experiment, Stanford prison experiment), and this has also been criticized for ethical reasons.

To protect the rights and well-being of research participants, and at the same time discover meaningful results and insights into human behavior, virtually all social psychology research must pass an ethical review process. At most colleges and universities, this is conducted by an ethics committee or institutional review board. This group examines the proposed research to make sure that no harm is done to the participants, and that the benefits of the study outweigh any possible risks or discomforts to people taking part in the study.

Furthermore, a process of informed consent is often used to make sure that volunteers know what will happen in the experiment and understand that they are allowed to quit the experiment at any time. A debriefing is typically done at the conclusion of the experiment in order to reveal any deceptions used and generally make sure that the participants are unharmed by the procedures. Today, most research in social psychology involves no more risk of harm than can be expected from routine psychological testing or normal daily activities.

Famous experiments in social psychology

Well known experiments and studies that have influenced social psychology include:

- The Asch conformity experiments in the 1950s, a series of studies by Solomon Asch (1955) that starkly demonstrated the power of conformity on people's estimation of the length of lines. On over a third of the trials, participants conformed to the majority, even though the majority judgment was clearly wrong. Seventy-five percent of the participants conformed at least once during the experiment.

- Muzafer Sherif's (1954) Robbers' Cave Experiment, which divided boys into two competing groups to explore how much hostility and aggression would emerge. This led to the development of realistic group conflict theory, based on the finding that intergroup conflict that emerged through competition over resources was reduced through focus on superordinate goals (goals so large that it required more than one group to achieve the goal).

- Leon Festinger's cognitive dissonance experiment, in which subjects were asked to perform a boring task. They were divided into two groups and given two different pay scales. At the end of the study, participants who were paid $1 to say that they enjoyed the task and another group of participants were paid $20 to give the same lie. The first group ($1) later believed that they liked the task better than the second group ($20). People justified the lie by changing their previously unfavorable attitudes about the task (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959).

- The Milgram experiment, which studied how far people would go to obey an authority figure. Following the events of the Holocaust in World War II, Stanley Milgram's (1975) experiment showed that normal American citizens were capable of following orders to the point of causing extreme suffering in an innocent human being.

- Albert Bandura's Bobo doll experiment, which demonstrated how aggression is learned by imitation (Bandura, et al., 1961). This was one of the first studies in a long line of research showing how exposure to media violence leads to aggressive behavior in the observers.

- The Stanford prison experiment by Philip Zimbardo, where a simulated exercise between student prisoners and guards showed how far people would follow an adopted role. This was an important demonstration of the power of the immediate social situation, and its capacity to overwhelm normal personality traits (Haney, Banks, & Zimbardo, 1973).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adler, L.L., and U.P. Gielen (eds.). 2001. Cross-Cultural Topics in Psychology, 2nd edition. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0275969738.

- Allport, G.W. 1998. The Historical Background of Social Psychology. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195213768.

- Ambady, N., and R. Rosenthal. 1992. Thin slices of expressive behavior as predictors of interpersonal consequences: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 111: 256-274.

- Argyle, Michael [1967] 1999. The Psychology of Interpersonal Behaviour. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0140172744

- Aronson, Eliot. [1972] 2007. The Social Animal. New York, NY: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1429203166

- Aronson, Eliot, Timothy D. Wilson, and Robin M. Akert. 2009. Social Psychology (7th Edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0138144784

- Asch, S.E. [1952] 1987. Social Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198521723

- Asch, S.E. 1955. Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American, p. 31-35.

- Bandura, A., D. Ross, and S. A. Ross. 1961. Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63: 575-582.

- Batson, C.D. 1998. Altruism and prosocial behavior. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey, (eds.), The Handbook of Social Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195213769

- Bem, D. 1970. Beliefs, Attitudes, and Human Affairs. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 081858906X

- Borkenau, P., and A. Liebler. 1992. Trait inferences: Sources of validity at zero acquaintance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62: 645-647.

- Cialdini, R.B. 2000. Influence: Science and Practice. Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0321011473.

- Correll, J., B. Park, C.M. Judd, and B. Wittenbrink. 2002. The police officer's dilemma: Using ethnicity to disambiguate potentially threatening individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83: 1314-1329.

- Cote, J.E. and C.G. Levine. 2002. Identity Formation, Agency, and Culture. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 978-0805837964.

- Cronbach, L. J. 1955. Processes affecting scores on "understanding of others" and "assumed similarity." Psychological Bulletin, 52: 177-193.

- Festinger, L. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804701310.

- Festinger, L., and J.M. Carlsmith. 1959. Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58: 203-211.

- Funder, D. C. 1995. On the accuracy of personality judgment: A realistic approach". Psychological Review, 102: 652-670.

- Gielen U.P., and L.L. Adler (eds.). 1992. Psychology in International Perspective: 50 years of the International Council of Psychologists. Lisse, Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers.

- Gladwell M. 2005. Blink: The Power of Thinking without Thinking. Boston, MA: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0739455296.

- Gergen, K.J. 1973. Social psychology as history. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 26: 309-320.

- Guzewicz, T.D., and H. Takooshian. 1992. Development of a short-form scale of public attitudes toward homelessness. Journal of Social Distress & the Homeless, 1(1): 67-79.

- Haney, C., W.C. Banks, and P. G. Zimbardo. 1973. Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison. International Journal of Criminology and Penology, 1: 69-97.

- Janis, I.L. 1972. Victims of Groupthink. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0395140444.

- Kenny, D.A. 1994. Interpersonal Perception: A Social Relations Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-0898621143.

- Kelley, C.P., and S.D.S. Vichinstein. 2007. An Introduction to D.I.R.P. Theory: Disentangling Interspecies Reproduction Patterns. Presented at the Annual Conference of the ISAA.

- Latane, B. 1981. The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist, 36: 343-356.

- Lewin, K. [1951] 1975. Field Theory in Social Science: Selected Theoretical Papers. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0837172365

- Mesoudi, A. 2007. Using the methods of experimental social psychology to study cultural evolution. Journal of Social, Evolutionary & Cultural Psychology, 1(2): 35-58.

- Milgram, S. [1975] 2004. Obedience to Authority. Harper and Bros. ISBN 978-0060737283.

- Perloff, R.M. 2007. The Dynamics of Persuasion. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. ISBN 978-0805863604.

- Rieber, R.W., H. Takooshian, and H. Iglesias. 2002. The case of Sybil in the teaching of psychology. Journal of Social Distress & the Homeless, 11(4): 355-360.

- Robinson, Peter. 2002. Obituary: Michael Argyle. The Guardian. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- Schaller, M., J.A. Simpson, and D.T. Kenrick. 2006. Evolution and Social Psychology (Frontiers of Social Psychology). New York: Psychology Press. ISBN 1841694177.

- Sewell, W.H. 1989. Some reflections on the golden age of interdisciplinary social psychology. Annual Review of Sociology. Vol. 15.

- Sherif, M. 1954. Experiments in group conflict. Scientific American, 195: 54-58.

- Smith, Peter B. 2009. Is there an indigenous European social psychology?. Reprinted from Wedding, D., & Stevens, M. J. (Eds). (2009). Psychology: IUPsyS Global Resource (Edition 2009) [CD-ROM]. International Journal of Psychology, 44 (Suppl. 1). Retrieved September 26, 2011.

- Sternberg, R. J. 1986. A triangular theory of love. Psychological Review, 93: 119-135.

- Tajfel, H., and J.C. Turner. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel and W.G. Austin (eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Chicago: Nelson-Hall. ISBN 978-0830410750.

- Takooshian, H. 2005. Reviewing 100 years of cross-national work on intelligence. PsycCRITIQUES, 50(12).

- Takooshian, H., N. Mrinal, and U. Mrinal. 2001. Research methods for studies in the field. In L. L. Adler & U. P. Gielen (Eds.), Cross-Cultural Topics in Psychology, 2nd edition. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0275969738.

- Takooshian, H., and W. M. Verdi. 1995. Assessment of attitudes toward terrorism. In L. L. Adler, & F. L. Denmark (eds.), Violence and the Prevention of Violence. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0275948733.

- Triplett, N. 1898. The dynamogenic factors in pacemaking and competition. American Journal of Psychology. 9: 507-533.

- Vazier, S. & S.D. Gosling. 2004. e-Perceptions: Personality impressions based on personal websites. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87: 123-132.

- Watson, D. 1989. Strangers' ratings of the five robust personality factors: Evidence of a surprising convergence with self-report. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57: 120-128.

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2023.

- Society of Experimental Social Psychology

- Social Psychology Network

- Social Psychology at The Psychology Wiki

- Social Psychology - Basics

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.