| Հավաքական անվտանգության պայմանագրի կազմակերպություն (Armenian) Арганізацыя Дамовы аб калектыўнай бясьпецы (Belarusian) Ұжымдық қауіпсіздік туралы шарт ұйымы Ūjymdyq Qauıpsızdık Turaly Şart Ūıymy (Kazakh) Жамааттык коопсуздук жөнүндө келишим уюму (Kyrgyz) Организация Договора о коллективной безопасности (Russian) Созмони Аҳдномаи амнияти дастаҷамъӣ (Tajik) | |

Emblem | |

Flag | |

| |

| Abbreviation | CSTO |

|---|---|

| Formation |

|

| Type | Military alliance |

| Headquarters | Moscow, Russia |

| Location | |

Membership | 6 members 1 observer 3 former members |

Official language | Russian |

Secretary General | Stanislav Zas |

Chairman | Nikol Pashinyan |

| Website | odkb-csto.org |

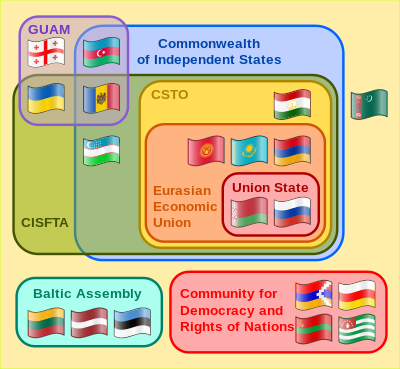

The Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO; Russian: Организация Договора о коллективной безопасности, romanized: Organizatsiya Dogovora o kollektivnoy bezopasnosti; Russian: ОДКБ, romanized: ODKB) is an intergovernmental military alliance in Eurasia. The CSTO consists of select post-Soviet states. The treaty had its origins in the Soviet Armed Forces, which was replaced by the United Armed Forces of the Commonwealth of Independent States, and then by the successor armed forces of the respective independent states.

Similar to Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty, Article 4 of the Collective Security Treaty (CST) establishes that an aggression against one signatory would be perceived as an aggression against all. The CSTO charter reaffirmed the desire of all participating states to abstain from the use or threat of force. Signatories would not be able to join other military alliances.[3]

Activities[edit]

Exercises[edit]

The CSTO holds yearly military command exercises for the CSTO nations to have an opportunity to improve inter-organization cooperation. A CSTO military exercise called "Rubezh 2008" was hosted in Armenia, where a combined total of 4,000 troops from all seven constituent CSTO member countries conducted operative, strategic and tactical training with an emphasis towards furthering efficiency of the collective security element of the CSTO partnership.[4]

The largest of such exercises was held in Southern Russia and central Asia in 2011, consisting of more than 10,000 troops and 70 combat aircraft.[5] In order to deploy military bases of a third country in the territory of the CSTO member-states, it is necessary to obtain the official consent of all its members.[6] It also employs a "rotating presidency" system in which the country leading the CSTO alternates every year.[7]

Scenarios of the exercises are grouped around:[8]

- "Cooperation" command-post exercises of the collective forces of operative reaction,

- "Search" special maneuvers with the participation of intelligence forces,

- "Echelon" material and technical supply drills

- "Frontier"

- "Endurable Brotherhood"

CSTO Parliamentary Assembly[edit]

Similar to NATO, the CSTO maintains a Parliamentary Assembly.[9]

Peacekeeping force[edit]

On 6 October 2007, CSTO members agreed to a major expansion of the organization that would create a CSTO peacekeeping force that could deploy under a U.N. mandate or without one in its member states. The expansion would also allow all members to purchase Russian weapons at the same price as Russia.[10]

In January 2022, the CSTO deployed 2,000 of its peacekeepers to Kazakhstan.[11]

Collective Rapid Reaction Force[edit]

On 4 February 2009, an agreement to create the Collective Rapid Reaction Force (KSOR) (Russian: Коллекти́вные си́лы операти́вного реаги́рования (КСОР)) was reached by five of the seven members, with plans finalized on 14 June. The force is intended to be used to repulse military aggression, conduct anti-terrorist operations, fight transnational crime and drug trafficking, and neutralize the effects of natural disasters.[12][13]

Belarus and Uzbekistan initially refrained from signing on to the agreement. Belarus did so because of a trade dispute with Russia, and Uzbekistan due to general concerns. Belarus signed the agreement the following October, while Uzbekistan has never done so. A source in the Russian delegation said Uzbekistan would not participate in the collective force on a permanent basis but would "delegate" its detachments to take part in operations on an ad hoc basis.[12][13]

On 3 August 2009, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Uzbekistan criticized plans by Russia to establish a military base in southern Kyrgyzstan for the CSTO rapid reaction force, stating,

The implementation of such projects on complex and unpredictable territory, where the borders of three Central Asian republics directly converge, may give impetus to the strengthening of militarization processes and initiate all kinds of nationalistic confrontations. […] Also, it could lead to the appearance of radical extremist forces that could lead to serious destabilization in this vast region.[14]

History[edit]

Foundation[edit]

On 15 May 1992, six post-Soviet states belonging to the Commonwealth of Independent States — Russia, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan—signed the Collective Security Treaty (also referred to as the Tashkent Pact or Tashkent Treaty).[15]

Three other post-Soviet states—Azerbaijan, Belarus, and Georgia—signed in 1993 and the treaty took effect in 1994. In 1999, six of the nine—all but Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Uzbekistan—agreed to renew the treaty for five more years. In 2002, those six agreed to create the Collective Security Treaty Organization as a military alliance.[16]

The CSTO was set to last for a 5-year period unless extended. On 2 April 1999, six members of the CST signed a protocol renewing the treaty for another five-year period – Azerbaijan, Georgia and Uzbekistan refused to sign and withdrew from the treaty instead.[16] At the same time Uzbekistan joined the GUAM group, established in 1997 by Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Moldova, and largely seen as intending to counter Russian influence in the region.[17]

2005 and later[edit]

During 2005, the CSTO partners conducted some common military exercises.

Uzbekistan later withdrew from GUAM in 2005 and joined the CSTO in 2006 as a full member and its membership was later ratified by the Uzbek parliament on 28 March 2008.[18]

In June 2007, Kyrgyzstan assumed the rotating CSTO presidency.

In October 2007, the CSTO signed an agreement with the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), in the Tajik capital of Dushanbe, to broaden cooperation on issues such as security, crime, and drug trafficking.[19]

On 6 October 2007, CSTO members agreed to a major expansion of the organization that would create a CSTO peacekeeping force that could deploy under a U.N. mandate or without one in its member states. The expansion would also allow all members to purchase Russian weapons at the same price as Russia.[20]

On 29 August 2008, Russia announced it would seek CSTO recognition of the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Three days earlier, on 26 August, Russia recognized the independence of Georgia's breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.[21]

On 5 September 2008, Armenia assumed the rotating CSTO presidency during a CSTO meeting in Moscow, Russia.[22]

In 2009, Belarus boycotted the CSTO summit due to their Milk War with Russia.[23] After refusing to attend a CSTO summit in 2009, Lukashenko said: "Why should my men fight in Kazakhstan? Mothers would ask me why I sent their sons to fight so far from Belarus. For what? For a unified energy market? That is not what lives depend on. No!"[24]

After Kurmanbek Bakiyev was ousted from office as President of Kyrgyzstan as a result of riots in Kyrgyzstan in April 2010, he was granted asylum in Belarus. Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko expressed doubt about the future of the CSTO for failing to prevent Bakiyev's overthrow, stating: "What sort of organization is this one, if there is bloodshed in one of our member states and an anticonstitutional coup d'état takes place, and this body keeps silent?"[25]

Lukashenko had previously accused Russia of punishing Belarus with economic sanctions after Lukashenko's refusal to recognize the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, stating: "The economy serves as the basis for our common security. But if Belarus's closest CSTO ally is trying ... to destroy this basis and de facto put the Belarusians on their knees, how can one talk about consolidating collective security in the CSTO space?"[26]

During a trip to Ukraine to extend Russia's lease of the Crimean port Sevastopol in return for discounted natural gas supplies, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev was asked about whether Belarus could expect a similar deal and responded: "Real partnership is one thing and a declaration of intentions is another; reaching agreement on working seriously, meeting each other halfway, helping each other is one thing and making decisions about granting permanent residence to people who have lost their job is another." The Belarusian President defended himself against this criticism by citing former Russian President Vladimir Putin's invitation of Askar Akayev to Russia after he was ousted as President of Kyrgyzstan during the 2005 Tulip Revolution.[27]

The following month, President Medvedev ordered the CEO of Russia's natural gas monopoly Gazprom to cut gas supplies to Belarus in a dispute over outstanding debts.[28] Subsequently, the Russian television channel NTV, run by Gazprom, aired a documentary film which compared Lukashenko to Bakiyev.[29] Then the Russian President's foreign policy adviser Sergei Prikhodko threatened to publish the transcript of a CSTO meeting where Lukashenko said that his administration would recognize Abkhazian and South Ossetian independence.[30]

In June 2010, ethnic clashes broke out between ethnic Kyrgyz and Uzbeks in southern Kyrgyzstan, leading interim Kyrgyz President Roza Otunbayeva to request the assistance of Russian troops to quell the disturbances. Kurmanbek Bakiyev denied charges that his supporters were behind the ethnic conflict and called on the CSTO to intervene.[31] Askar Akayev also called for the CSTO to send troops, saying: "Our priority task right now should be to extinguish this flame of enmity. It is very likely that we will need CSTO peacekeepers to do that."[citation needed] The organisation was considered by some[who?] a "paper tiger" since it failed to intervene.[32]

Russian President Dmitry Medvedev said that "only in the case of a foreign intrusion and an attempt to externally seize power can we state that there is an attack against the CSTO", and that, "all the problems of Kyrgyzstan have internal roots", while CSTO Secretary General Nikolai Bordyuzha called the violence "purely a domestic affair".[33] Later, however, Bordyuzha admitted that the CSTO response may have been inadequate and claimed that "foreign mercenaries" provoked the Kyrgyz violence against ethnic Uzbek minorities.[34]

On 21 July 2010, interim Kyrgyz President Roza Otunbayeva called for the introduction of CSTO police units to southern Kyrgyzstan saying: "I think it's important to introduce CSTO police forces there, since we're unable to guarantee people's rights on our own." She also added: "I'm not seeking the CSTO's embrace and I don't feel like bringing them here to stay but the bloodletting there will continue otherwise."[35] Only weeks later the deputy chairman of Otubayeva's interim Kyrgyz government complained that their appeals for help from the CSTO had been ignored.[36] The CSTO was unable to agree on providing military assistance to Kyrgyzstan at a meeting in Yerevan, Armenia, which was attended by Roza Otunbayeva as well as Alexander Lukashenko.[37]

On 10 December 2010, the member states approved a declaration establishing a CSTO peacekeeping force and a declaration of the CSTO member states, in addition to signing a package of joint documents.[38]

Since 21 December 2011, the Treaty parties can veto the establishment of new foreign military bases in the member states of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). Additionally, Kazakhstan took over the rotating presidency of the CSTO from Belarus.[6]

On 28 June 2012, Uzbekistan suspended its membership in the CSTO.[39]

In August 2014, 3,000 soldiers from the members of Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Russia and Tajikistan participated in psychological and cyber warfare exercises in Kazakhstan under war games managed by CSTO.[40]

On 19 March 2015, the CSTO Secretary General Nikolai Bordyuzha offered to send a peacekeeping mission to Donbas, Ukraine. "The CSTO has a peacekeeping capacity. Our peacekeepers continuously undergo corresponding training. If such a decision is taken by the United Nations, we stand ready to provide peacekeeping units".[41]

In July 2021, CTSO Secretary-General Stanislav Zas was criticised by Armenian politicians for calling an incursion by Azerbaijani forces onto Armenian territory a "border incident", where the CTSO remained inactive during the conflict.[42]

In July 2021, Tajikistan appealed to members of CSTO for help in dealing with security challenges emerging from neighboring Afghanistan.[43] Thousands of Afghans, including police and government troops, fled to Tajikistan after Taliban insurgents took control of many parts of Afghanistan.[44]

On 5 January 2022, CSTO peacekeepers were announced to be deployed to Kazakhstan in response to anti-government unrest in the country.[45] On 11 January the same year, CSTO forces began their withdrawal from Kazakhstan.[46]

Membership[edit]

Member states[edit]

Member states of the Collective Security Treaty Organization:

| Country | Membership | Year of entry |

|---|---|---|

| full member | 1994 | |

| full member | 1994 | |

| full member | 1994 | |

| full member | 1994 | |

| full member | 1994 | |

| full member | 1994 |

Former member states[edit]

| Country | Membership | Year of entry | Year of withdrawal |

|---|---|---|---|

| former member state | 1994 | 1999 | |

| former member state | 1994 | 1999 | |

| former member state | 1994 (first time) 2006 (second time) |

1999 (first time) 2012 (second time) |

Observer states in the CSTO Parliamentary Assembly[edit]

| Country | Participating Body | Membership | Year of entry |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia | non-member observer state | 2013 | |

| Parliamentary Assembly of the Union of Belarus and Russia | non-member observer state | 1999 |

Potential membership[edit]

In May 2007, the CSTO secretary-general Nikolai Bordyuzha suggested Iran could join the CSTO saying, "The CSTO is an open organization. If Iran applies in accordance with our charter, we will consider the application".[47] If Iran joined it would be the first state outside the former Soviet Union to become a member of the organization.

The National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia and the Wolesi Jirga (lower house) of the National Assembly of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan were accorded observer status in the CSTO Parliamentary Assembly in 2013, though the Islamic Republic collapsed in 2021 as the Taliban took over.[48] Also, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Union of Belarus and Russia has observer status in the CSTO Parliamentary Assembly.[49]

In 2021, Uzbekistan, after becoming observer to EAEU on 11 December 2020,[50] conducted a bilateral military exercise with Russia and trilateral military exercise with Russia and Tajikistan, while its president joined a CSTO meeting as a guest, sparking rumours about potential reentry into CSTO.[51]

List of Secretaries-General[edit]

The following have served as heads of the CSTO:[52]

Vladimir Zemsky (October 1996 – March 2000)

Vladimir Zemsky (October 1996 – March 2000) Valeriy Nikolayenko (May 2000 – April 2003)

Valeriy Nikolayenko (May 2000 – April 2003) Nikolay Bordyuzha (28 April 2003 – 31 December 2016)

Nikolay Bordyuzha (28 April 2003 – 31 December 2016) Valery Semerikov (acting) (1 January 2017 – 2 May 2017)

Valery Semerikov (acting) (1 January 2017 – 2 May 2017) Yuri Khatchaturov (2 May 2017 – 2 November 2018)

Yuri Khatchaturov (2 May 2017 – 2 November 2018) Valery Semerikov (acting) (1 November 2018 – 31 December 2019)

Valery Semerikov (acting) (1 November 2018 – 31 December 2019) Stanislav Zas (since 1 January 2020)

Stanislav Zas (since 1 January 2020)

Policy agenda[edit]

Information technology and cyber security[edit]

The member states adopted measures to counter cyber security threats and information technology crimes in a Foreign Ministers Council meeting in Minsk, Belarus.[53] Foreign Minister Abdrakhmanov put forward a proposal to establishing a Cyber Shield system.[53]

Military personnel[edit]

The following list is sourced from the 2018 edition of "The Military Balance" published annually by the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

| Flag | Country | Active military | Reserve military | Paramilitary | Total | Per 1000 capita (total). |

Per 1000 capita (active) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia[54][Note 1][Note 2] | 44,800 | 210,000 | 4,300 | 259,100 | 85.1 | 14.7 | |

| Belarus[55] | 65,000 | 290,000 | 110,000 | 465,000 | 48.7 | 6.8 | |

| Kazakhstan[56] | 108,000 | 132,000 | 30,000 | 270,000 | 13.8 | 5.5 | |

| Kyrgyzstan[57] | 10,900 | 0 | 9,500 | 20,400 | 3.5 | 1.9 | |

| Russia[58][Note 3] | 900,000 | 2,000,000 | 554,000 | 3,454,000 | 24.3 | 6.3 | |

| Tajikistan[59] | 8,800 | 0 | 7,500 | 16,300 | 1.9 | 1 |

See also[edit]

- Soviet Armed Forces

- Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

- Community for Democracy and Rights of Nations

- Eurasian Economic Community (EURASEC)

- Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU)

- GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development (GUAM)

- Military alliance

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)

- Post-Soviet states

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO)

- Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO)

- Warsaw Pact

Notes[edit]

- ^ The reserve military of Armenia consists mostly of ex-conscripts who have seen service within the last 15 years.

- ^ Does not include Army forces of Artsakh, which has an Armenian backed army.

- ^ The potential reserve personnel of Russia may be as high as 20 million, depending on how the figures are counted. However, an est. 2 million have seen military service within the last 5 years.

References[edit]

- ^ Taylor & Francis (2020). "Republic of Crimea". The Territories of the Russian Federation 2020. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-00706-7.

Note: The territories of the Crimean peninsula, comprising Sevastopol City and the Republic of Crimea, remained internationally recognised as constituting part of Ukraine, following their annexation by Russia in March 2014.

- ^ "MULTILATERAL Treaty on collective security. Concluded at Tashkent on 15 May 1992. Correction of 18 May 1995 of the above-mentioned Treaty. Correction of 9 October 1995 of the above-mentioned Treaty" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 January 2022.

- ^ Obydenkova, Anastassia (23 November 2010). "Comparative regionalism: Eurasian cooperation and European integration. The case for neofunctionalism?". Journal of Eurasian Studies. 2 (2): 91. doi:10.1016/j.euras.2011.03.001.

- ^ Sputnik (22 July 2008). "Former Soviet states boost defense capability in joint drills". Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ^ J. Berkshire Miller, The Diplomat. "Russia Launches War Games". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ a b Vladimir Radyuhin (22 December 2011). "CSTO tightens foreign base norms". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Russian-Led CSTO To Hold Military Maneuvers In Central Asia In October". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 29 April 2022.

- ^ "Iran, other states might become observers at CSTO parliamentary assembly — Naryshkin". TASS. 6 November 2014.

- ^ "Gendarme of Eurasia – Kommersant Moscow". Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- ^ Grynszpan, Emmanuel (7 June 2022). "Moscow's influence wanes in Central Asian countries". Le Monde.

- ^ a b Sputnik (4 February 2009). "CSTO's rapid-reaction force to equal NATO's – Medvedev". Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ a b With Russian Prodding, CSTO Begins Taking Shape Archived 24 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 24 November 2009

- ^ Tashkent Throws Temper Tantrum over New Russian Base in Kyrgyzstan Archived 16 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, EurasiaNet, 3 August 2009

- ^ ed, Alexei G. Arbatov ... (1999). Russia and the West : the 21st century security environment. Armonk, NY [u.a.]: Sharpe. p. 62. ISBN 978-0765604323. Archived from the original on 23 August 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ a b "From Treaty to Organization".

- ^ "Uzbekistan: Tashkent Withdraws From GUUAM, Remaining Members Forge Ahead". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 18 June 2002. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Daily Times – Leading News Resource of Pakistan". Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- ^ "Gendarme of Eurasia – Kommersant Moscow". Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- ^ "Kremlin announces that South Ossetia will join 'one united Russian state". Archived from the original on 3 September 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2008.

- ^ "CSTO Security Councils Secretaries meet in Yerevan". PanARMENIAN.Net. Archived from the original on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ "Belarus leader may snub Moscow security meet". Reuters. 13 June 2009. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- ^ "Lukashenko Plays Coy With Kremlin" Archived 22 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Moscow Times, 28 August 2009.

- ^ Belarus leader raps Russia, may snub security summit Archived 29 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 25 April 2010.

- ^ Belarus-Russia rift widens, Minsk snubs Moscow meet Archived 26 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 14 June 2009.

- ^ Lukashenka dismisses Moscow's criticism over Bakiyev Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Belaplan, 25 April 2010.

- ^ Russia Cuts Gas Supplies to Belarus Archived 24 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, VOANews, 21 June 2010.

- ^ Russia and Belarus: It takes one to know one Archived 26 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Economist, 22 July 2010.

- ^ Tensions flare between Kremlin, Belarus strongman Archived 24 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Agence France-Presse, 14 August 2010.

- ^ Moscow-led bloc may try to quell Kyrgyz clashes, Reuters, 14 June 2010.

- ^ "CSTO Faces New Wave Of Criticism Over Ineffectiveness | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Kyrgyzstan tests Russia's regional commitments" Archived 2 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, GlobalPost, 15 June 2010.

- ^ "CSTO Chief Says Foreign Mercenaries Provoked Race Riots In Kyrgyzstan" Archived 6 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Eurasia Review, 1 July 2010.

- ^ Kyrgyzstan takes decision on deploying CIS police force in South[permanent dead link], Itar-Tass, 21 July 2010.

- ^ "Kyrgyz Official Criticizes Foreign Partners" Archived 12 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 11 August 2010.

- ^ "Russian-led bloc undecided on aid for Kyrgyzstan" Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Reuters, 20 August 2010.

- ^ "Meeting of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation". President of Russia. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ^ "Uzbekistan Suspends Its Membership in CSTO". The Gazette of Central Asia. 29 June 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ "Armenia to participate in Kazakhstan CSTO drills". Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- ^ "Bordyuzha: CSTO ready to deploy its peacekeepers to resolve conflict in Ukraine". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ "Apparent inaction gives rise to criticism of CSTO in Armenia". OC Media. 9 July 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ "Tajikistan Reportedly Calls On Allies For Help With Security Challenges From Afghanistan". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty.

- ^ "Tajikistan asks Russia-led bloc for help on Afghan border". Reuters. 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Armenia says peacekeepers from Russian-led alliance to go to Kazakhstan". Reuters. 5 January 2022.

- ^ "Russian troops to quit Kazakhstan, says president, taking aim at the elite". Reuters. 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Iran may join security group led by Russia - Indian Express". archive.indianexpress.com. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ "Парламентские делегации Республики Сербия и Исламской Республики Афганистан получили статус наблюдателей при Парламентской Ассамблее ОДКБ". odkb-csto.org. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ^ "Государства-члены ПА ОДКБ".

- ^ "Uzbekistan, Cuba granted observer status at Eurasian Economic Union". eng.belta.by. 11 December 2020. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ "Is Uzbekistan on the Verge of Rejoining the CSTO?".

- ^ "Leadership history". en.odkb-csto.org. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ a b "CSTO foreign ministers adopt measures to curb IT crime during Minsk meeting". The Astana Times. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ IISS 2018, pp. 181

- ^ IISS 2018, pp. 185

- ^ IISS 2018, pp. 188

- ^ IISS 2018, pp. 190

- ^ IISS 2018, pp. 192

- ^ IISS 2018, pp. 207

Bibliography[edit]

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (14 February 2018). The Military Balance 2018. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781857439557.

- Rozanov, Anatoliy A.; Douha, Alena F. (2013). "Collective Security Treaty Organisation 2002 – 2012" (PDF). Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces.

- Douhan, A.F.; Rusakovich, А.V. (2016). "COLLECTIVE SECURITY TREATY ORGANIZATION AND CONTINGENCY PLANNING AFTER 2014" (PDF). Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces.

- Weitz, Richard (October 2018). "ASSESSING THE COLLECTIVE SECURITY TREATY ORGANIZATION: CAPABILITIES AND VULNERABILITIES" (PDF). United States Army War College Press.

External links[edit]

- CSTO Official Site (in Russian)

- CSTO Official Site (in English)

- Official Site of the Parliamentary Assembly of the CSTO (in Russian)

- The Charter of the CSTO