Electricity price forecasting (EPF) is a branch of energy forecasting which focuses on predicting the spot and forward prices in wholesale electricity markets. Over the last 15 years electricity price forecasts have become a fundamental input to energy companies’ decision-making mechanisms at the corporate level. Since the early 1990s, the process of deregulation and the introduction of competitive electricity markets have been reshaping the landscape of the traditionally monopolistic and government-controlled power sectors. Throughout Europe, North America and Australia, electricity is now traded under market rules using spot and derivative contracts.[1][2] However, electricity is a very special commodity: it is economically non-storable and power system stability requires a constant balance between production and consumption. At the same time, electricity demand depends on weather (temperature, wind speed, precipitation, etc.) and the intensity of business and everyday activities (on-peak vs. off-peak hours, weekdays vs. weekends, holidays, etc.). These unique characteristics lead to price dynamics not observed in any other market, exhibiting daily, weekly and often annual seasonality and abrupt, short-lived and generally unanticipated price spikes.

Extreme price volatility, which can be up to two orders of magnitude higher than that of any other commodity or financial asset, has forced market participants to hedge not only volume but also price risk. Price forecasts from a few hours to a few months ahead have become of particular interest to power portfolio managers. A power market company able to forecast the volatile wholesale prices with a reasonable level of accuracy can adjust its bidding strategy and its own production or consumption schedule in order to reduce the risk or maximize the profits in day-ahead trading.[3] A ballpark estimate of savings from a 1% reduction in the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of short-term price forecasts is $300,000 per year for a utility with 1GW peak load.[4]

Electricity price forecasting is the process of using mathematical models to predict what electricity prices will be in the future.

Forecasting methodology

The simplest model for day ahead forecasting is to ask each generation source to bid on blocks of generation and choose the cheapest bids. If not enough bids are submitted, the price is increased. If too many bids are submitted the price can reach zero or become negative. The offer price includes the generation cost as well as the transmission cost, along with any profit. Power can be sold or purchased from adjoining power pools.[5][6][7]

The concept of independent system operators (ISOs) fosters competition for generation among wholesale market participants by unbundling the operation of transmission and generation. ISOs use bid-based markets to determine economic dispatch.[8]

Wind and solar power are non-dispatchable. Such power is normally sold before any other bids, at a predetermined rate for each supplier. Any excess is sold to another grid operator, or stored, using pumped-storage hydroelectricity, or in the worst case, curtailed.[9] Curtailment could potentially significantly impact solar power's economic and environmental benefits at greater PV penetration levels.[10] Allocation is done by bidding.[11]

The effect of the recent introduction of smart grids and integrating distributed renewable generation has been increased uncertainty of future supply, demand and prices.[12] This uncertainty has driven much research into the topic of forecasting.

Driving factors

Electricity cannot be stored as easily as gas, it is produced at the exact moment of demand. All of the factors of supply and demand will, therefore, have an immediate impact on the price of electricity on the spot market. In addition to production costs, electricity prices are set by supply and demand.[13] However, some fundamental drivers are the most likely to be considered.

Short-term prices are impacted the most by the weather. Demand due to heating in the winter and cooling in the summer are the main drivers for seasonal price spikes.[14] Additional natural-gas fired capacity is driving down the price of electricity and increasing demand.

A country's natural resource endowment, as well as its regulations in place greatly influence tariffs from the supply side. The supply side of the electricity supply is most influenced by fuel prices, and CO2 allowance prices. The EU carbon prices have doubled since 2017, making it a significant driving factor of price.[15]

Weather

Studies show that demand for electricity is driven largely by temperature. Heating demand in the winter and cooling demand (air conditioners) in the summer are what primarily drive the seasonal peaks in most regions. Heating degree days and cooling degree days help measure energy consumption by referencing the outdoor temperature above and below 65 degrees Fahrenheit, a commonly accepted baseline.[16]

In terms of renewable sources like solar and wind, weather impacts supply. California's duck curve shows the difference between electricity demand and the amount of solar energy available throughout the day. On a sunny day, solar power floods the electricity generation market and then drops during the evening, when electricity demand peaks.[10]

Hydropower availability

Snowpack, streamflows, seasonality, salmon, etc. all affect the amount of water that can flow through a dam at any given time. Forecasting these variables predicts the available potential energy for a dam for a given period.[17] Some regions such as Pakistan, Egypt, China and the Pacific Northwest get significant generation from hydroelectric dams. In 2015, SAIDI and SAIFI more than doubled from the previous year in Zambia due to low water reserves in their hydroelectric dams caused by insufficient rainfall.[18]

Power plant and transmission outages

Whether planned or unplanned, outages affect the total amount of power that is available to the grid. Outages undermine electricity supply, which in turn affects the price.[18]

Economic health

During times of economic hardship, many factories cut back production due to a reduction of consumer demand and therefore reduce production-related electrical demand.[19]

Government regulation

Governments may choose to make electricity tariffs affordable for their population through subsidies to producers and consumers. Most countries characterized as having low energy access have electric power utilities that do not recover any of their capital and operating costs, due to high subsidy levels.[20]

Taxonomy of modeling approaches

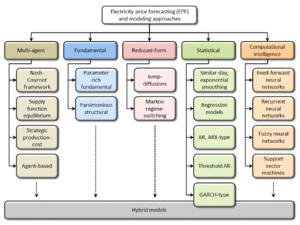

A variety of methods and ideas have been tried for EPF over the last 15 years, with varying degrees of success. They can be broadly classified into six groups.[1]

Multi-agent models

Multi-agent (multi-agent simulation, equilibrium, game theoretic) models simulate the operation of a system of heterogeneous agents (generating units, companies) interacting with each other, and build the price process by matching the demand and supply in the market.[21] This class includes cost-based models (or production-cost models, PCM),[22] equilibrium or game theoretic approaches (like the Nash-Cournot framework, supply function equilibrium - SFE, strategic production-cost models - SPCM)[23][24][25] and agent-based models.[26]

Multi-agent models generally focus on qualitative issues rather than quantitative results. They may provide insights as to whether or not prices will be above marginal costs, and how this might influence the players’ outcomes. However, they pose problems if more quantitative conclusions have to be drawn, particularly if electricity prices have to be predicted with a high level of precision.

Fundamental models

Fundamental (structural) methods try to capture the basic physical and economic relationships which are present in the production and trading of electricity.[27] The functional associations between fundamental drivers (loads, weather conditions, system parameters, etc.) are postulated, and the fundamental inputs are modeled and predicted independently, often via statistical, reduced-form or computational intelligence techniques. In general, two subclasses of fundamental models can be identified: parameter rich models[28] and parsimonious structural models[29] of supply and demand.

Two major challenges arise in the practical implementation of fundamental models: data availability and incorporation of stochastic fluctuations of the fundamental drivers. In building the model, we make specific assumptions about physical and economic relationships in the marketplace, and therefore the price projections generated by the models are very sensitive to violations of these assumptions.

Reduced-form models

Reduced-form (quantitative, stochastic) models characterize the statistical properties of electricity prices over time, with the ultimate objective of derivatives valuation and risk management.[2][3][27] Their main intention is not to provide accurate hourly price forecasts, but rather to replicate the main characteristics of daily electricity prices, like marginal distributions at future time points, price dynamics, and correlations between commodity prices. If the price process chosen is not appropriate for capturing the main properties of electricity prices, the results from the model are likely to be unreliable. However, if the model is too complex, the computational burden will prevent its use on-line in trading departments. Depending on the type of market under consideration, reduced-form models can be classified as:

- Spot price models, which provide a parsimonious representation of the dynamics of spot prices. Their main drawback is the problem of pricing derivatives, i.e., the identification of the risk premium linking spot and forward prices.[30] The two most popular subclasses include jump-diffusion[31][32] and Markov regime-switching[33] models.

- Forward price models allow for the pricing of derivatives in a straightforward manner (but only of those written on the forward price of electricity). However, they too have their limitations; most importantly, the lack of data that can be used for calibration and the inability to derive the properties of spot prices from the analysis of forward curves.[28][34]

Statistical models

Statistical (econometric, technical analysis) methods forecast the current price by using a mathematical combination of the previous prices and/or previous or current values of exogenous factors, typically consumption and production figures, or weather variables.[1] The two most important categories are additive and multiplicative models. They differ in whether the predicted price is the sum (additive) of a number of components or the product (multiplicative) of a number of factors. The former are far more popular, but the two are closely related - a multiplicative model for prices can be transformed into an additive model for log-prices. Statistical models are attractive because some physical interpretation may be attached to their components, thus allowing engineers and system operators to understand their behavior. They are often criticized for their limited ability to model the (usually) nonlinear behavior of electricity prices and related fundamental variables. However, in practical applications, their performances are not worse than those of the non-linear computational intelligence methods (see below). For instance, in the load forecasting track of the Global Energy Forecasting Competition (GEFCom2012) attracting hundreds of participants worldwide, the top four winning entries used regression-type models.

Statistical models constitute a very rich class which includes:

- Similar-day and exponential smoothing[35] methods.

- Regression models.[36]

- Time series models without (AR, ARMA, ARIMA, Fractional ARIMA - FARIMA, Seasonal ARIMA - SARIMA, Threshold AR - TAR) and with exogenous variables (ARX, ARMAX, ARIMAX, SARIMAX, TARX).[3][35][37][38][39]

- Heteroskedastic time series models (GARCH, AR-GARCH).[3][40]

Computational intelligence models

Computational intelligence (artificial intelligence-based, machine learning, non-parametric, non-linear statistical) techniques combine elements of learning, evolution and fuzziness to create approaches that are capable of adapting to complex dynamic systems, and may be regarded as "intelligent" in this sense. Artificial neural networks,[37][41][42] fuzzy systems[41][43] and support vector machines (SVM)[44] are unquestionably the main classes of computational intelligence techniques in EPF. Their major strength is the ability to handle complexity and non-linearity. In general, computational intelligence methods are better at modeling these features of electricity prices than the statistical techniques (see above). At the same time, this flexibility is also their major weakness. The ability to adapt to nonlinear, spiky behaviors will not necessarily result in better point or probabilistic forecasts.

Hybrid models

Many of the modeling and price forecasting approaches considered in the literature are hybrid solutions, combining techniques from two or more of the groups listed above. Their classification is non-trivial, if possible at all. As an example of hybrid model AleaModel (AleaSoft) combines Neural Networks and Box Jenkins models.

Forecasting horizons

It is customary to talk about short-, medium- and long-term forecasting,[1] but there is no consensus in the literature as to what the thresholds should actually be:

- Short-term forecasting generally involves horizons from a few minutes up to a few days ahead, and is of prime importance in day-to-day market operations.

- Medium-term forecasting, from a few days to a few months ahead, is generally preferred for balance sheet calculations, risk management and derivatives pricing. In many cases, especially in electricity price forecasting, evaluation is based not on the actual point forecasts, but on the distributions of prices over certain future time periods. As this type of modeling has a long-standing tradition in finance, an inflow of "finance solutions" is observed.

- Long-term forecasting, with lead times measured in months, quarters or even years, concentrates on investment profitability analysis and planning, such as determining the future sites or fuel sources of power plants.

Future of electricity price forecasting

In his extensive review paper, Weron[1] looks ahead and speculates on the directions EPF will or should take over the next decade or so:

Fundamental price drivers and input variables

Seasonality

A key point in electricity spot price modeling and forecasting is the appropriate treatment of seasonality.[42][45] The electricity price exhibits seasonality at three levels: the daily and weekly, and to some extent - the annual. In short-term forecasting, the annual or long-term seasonality is usually ignored, but the daily and weekly patterns (including a separate treatment of holidays) are of prime importance. This, however, may not be the right approach. As Nowotarski and Weron[46] have recently shown, decomposing a series of electricity prices into a long-term seasonal and a stochastic component, modeling them independently and combining their forecasts can bring - contrary to a common belief - an accuracy gain compared to an approach in which a given model is calibrated to the prices themselves.

In mid-term forecasting, the daily patterns become less relevant and most EPF models work with average daily prices. However, the long-term trend-cycle component plays a crucial role. Its misspecification can introduce bias, which may lead to a bad estimate of the mean reversion level or of the price spike intensity and severity, and consequently, to underestimating the risk. Finally, in the long term, when the time horizon is measured in years, the daily, weekly and even annual seasonality may be ignored, and long-term trends dominate. Adequate treatment - both in-sample and out-of-sample - of seasonality has not been given enough attention in the literature so far.[47][48][49]

Variable selection

Another crucial issue in electricity price forecasting is the appropriate choice of explanatory variables.[1][50][51] Apart from historical electricity prices, the current spot price is dependent on a large set of fundamental drivers, including system loads, weather variables, fuel costs, the reserve margin (i.e., available generation minus/over predicted demand) and information about scheduled maintenance and forced outages. Although "pure price" models are sometimes used for EPF, in the most common day-ahead forecasting scenario most authors select a combination of these fundamental drivers, based on the heuristics and experience of the forecaster.[52] Very rarely has an automated selection or shrinkage procedure been carried out in EPF, especially for a large set of initial explanatory variables.[53] However, the machine learning literature provides viable tools that can be broadly classified into two categories:[54]

- Feature or subset selection, which involves identifying a subset of predictors that we believe to be influential, then fitting a model on the reduced set of variables.

- Shrinkage (also known as regularization), that fits the full model with all predictors using an algorithm that shrinks the estimated coefficients towards zero, which can significantly reduce their variance. Depending on what type of shrinkage is performed, some of the coefficients may be shrunk to zero itself. As such, some shrinkage methods - like the lasso - de facto perform variable selection.

Some of these techniques have been utilized in the context of EPF:

- stepwise regression,[55][56] including single step elimination,[50]

- Ridge regression,[53][57]

- lasso,[51][53][58][59][60]

- and elastic nets,[53]

but their use is not common. Further development and employment of methods for selecting the most effective input variables - from among the past electricity prices, as well as the past and predicted values of the fundamental drivers - is needed.

Spike forecasting and the reserve margin

When predicting spike occurrences or spot price volatility, one of the most influential fundamental variables is the reserve margin, also called surplus generation. It relates the available capacity (generation, supply), [math]\displaystyle{ C_t }[/math], to the demand (load), [math]\displaystyle{ D_t }[/math], at a given moment in time [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math]. The traditional engineering notion of the reserve margin defines it as the difference between the two, i.e., [math]\displaystyle{ RM = C_t - D_t }[/math], but many authors prefer to work with dimensionless ratios [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_t=D_t/C_t }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ R_t=C_t/D_t -1 }[/math] or the so-called capacity utilization [math]\displaystyle{ CU_t=1 - D_t/C_t }[/math].[1] Its rare application in EPF can be justified only by the difficulty of obtaining good quality reserve margin data. Given that more and more system operators (see e.g. http://www.elexon.co.uk) are disclosing such information nowadays, reserve margin data should be playing a significant role in EPF in the near future.

Probabilistic forecasts

The use of prediction intervals (PI) and densities, or probabilistic forecasting, has become much more common over the past three decades, as practitioners have come to understand the limitations of point forecasts.[61] Despite the bold move by the organizers of the Global Energy Forecasting Competition 2014 to require the participants to submit forecasts of the 99 percentiles of the predictive distribution (day-ahead in the price track) and not the point forecasts as in the 2012 edition,[62] this does not seem to be a common case in EPF as yet.

If PIs are computed at all, they usually are distribution-based (and approximated by the standard deviation of the model residuals[1]) or empirical. A new forecast combination (see below) technique has been introduced recently in the context of EPF. Quantile Regression Averaging (QRA) involves applying quantile regression to the point forecasts of a small number of individual forecasting models or experts, hence allows to leverage existing development of point forecasting.[63]

Combining forecasts

Consensus forecasts, also known as combining forecasts, forecast averaging or model averaging (in econometrics and statistics) and committee machines, ensemble averaging or expert aggregation (in machine learning), are predictions of the future that are created by combining several separate forecasts which have often been created using different methodologies. Despite their popularity in econometrics, averaged forecasts have not been used extensively in the context of electricity markets to date. There is some limited evidence on the adequacy of combining forecasts of electricity demand,[64] but it was only very recently that combining was used in EPF and only for point forecasts.[65][66] Combining probabilistic (i.e., interval and density) forecasts is much less popular, even in econometrics in general, mainly because of the increased complexity of the problem. Since Quantile Regression Averaging (QRA) allows to leverage existing development of point forecasting,[63] it is particularly attractive from a practical point of view and may become a popular tool in EPF in the near future.

Multivariate factor models

The literature on forecasting daily electricity prices has concentrated largely on models that use only information at the aggregated (i.e., daily) level. On the other hand, the very rich body of literature on forecasting intra-day prices has used disaggregated data (i.e., hourly or half-hourly), but generally has not explored the complex dependence structure of the multivariate price series.[1] If we want to explore the structure of intra-day electricity prices, we need to use dimension reduction methods; for instance, factor models with factors estimated as principal components (PC). Empirical evidence indicates that there are forecast improvements from incorporating disaggregated (i.e., hourly or zonal) data for predicting daily system prices, especially when the forecast horizon exceeds one week.[67][68] With the increase of computational power, the real-time calibration of these complex models will become feasible and we may expect to see more EPF applications of the multivariate framework in the coming years.

A universal test ground

All major review publications conclude that there are problems with comparing the methods developed and used in the EPF literature.[1][52] This is due mainly to the use of different datasets, different software implementations of the forecasting models and different error measures, but also to the lack of statistical rigor in many studies. This calls for a comprehensive, thorough study involving (i) the same datasets, (ii) the same robust error evaluation procedures, and (iii) statistical testing of the significance of one model's outperformance of another. To some extent, the Global Energy Forecasting Competition 2014 has addressed these issues. Yet more has to be done. A selection of the better-performing measures (weighted-MAE, seasonal MASE or RMSSE) should be used either exclusively or in conjunction with the more popular ones (MAPE, RMSE). The empirical results should be further tested for the significance of the differences in forecasting accuracies of the models.[65][66][67]

See also

- Energy forecasting

- Global Energy Forecasting Competitions

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Weron, Rafał (2014). [Open Access]. "Electricity price forecasting: A review of the state-of-the-art with a look into the future". International Journal of Forecasting 30 (4): 1030–1081. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2014.08.008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Bunn, Derek W., ed (2004). Modelling Prices in Competitive Electricity Markets. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-84860-9. http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-047084860X.html.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Weron, Rafał (2006). Modeling and Forecasting Electricity Loads and Prices: A Statistical Approach. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-05753-7. http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-047005753X.html.

- ↑ Hong, Tao (2015). "Crystal Ball Lessons in Predictive Analytics". EnergyBiz Magazine Spring: 35–37. http://www.energybiz.com/magazine/article/404587/crystal-ball-lessons-predictive-analytics.

- ↑ ISO NE

- ↑ "NY ISO Zone Maps". http://www.nyiso.com/public/markets_operations/market_data/maps/.

- ↑ "LMP Contour Map: Day-Ahead Market – Settlement Point Pricing". ERCOT. http://www.ercot.com/content/cdr/contours/damSpp1Hg.html.

- ↑ "FERC: Electric Power Markets – National Overview" (in en). https://www.ferc.gov/market-oversight/mkt-electric/overview.asp.

- ↑ "Wind Power and Electricity Markets". 2011. http://www.uwig.org/windinmarketstableOct2011.pdf.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Confronting the Duck Curve: How to Address Over-Generation of Solar Energy" (in en). https://www.energy.gov/eere/articles/confronting-duck-curve-how-address-over-generation-solar-energy.

- ↑ "Wayback Machine". Eirgrid. 16 August 2011. http://www.eirgrid.com/media/IFA+Overview.pdf.

- ↑ Nowotarski, Jakub; Weron, Rafał (2018). "Recent advances in electricity price forecasting: A review of probabilistic forecasting". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 81: 1548–1568. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.234. http://www.im.pwr.wroc.pl/~hugo/RePEc/wuu/wpaper/HSC_16_07.pdf.

- ↑ "The power market". Nord Pool Spot. http://www.nordpoolspot.com/How-does-it-work/.

- ↑ "Six Key Factors Driving Gas and Electricity Prices | APPI Energy". https://www.appienergy.com/news-and-resources/news/six-key-factors-driving-gas-and-electricity-prices/.

- ↑ "EU CO2 allowance prices continue to climb, hit Eur10.60/mt – Electric Power | Platts News Article & Story". https://www.platts.com/latest-news/electric-power/london/eu-co2-allowance-prices-continue-to-climb-hit-21492332.

- ↑ Robert Carver. "What Does It Take to Heat a New Room?". American Statistical Association. http://www.amstat.org/PUBLICATIONS/JSE/datasets/utility.txt.

- ↑ "More Reliable Forecasts for Water Flows Can Reduce Price of Electricity". Body of Knowledge on Infrastructure Regulation. 19 January 2010. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/01/100119074756.htm.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 J. Arlet. 2017. “Electricity sector constraints for firms across economies : a comparative analysis.” Doing business research notes; no.1. Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/409771499690745091/Electricity-sector-constraints-for-firms-across-economies-a-comparative-analysis p.10

- ↑ "Demand Forecasting for Electricity". Body of Knowledge on Infrastructure Regulation. http://regulationbodyofknowledge.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Mehra_Demand_Forecasting_for.pdf.

- ↑ C. Trimble, M. Kojima, I. Perez Arroyo, F. Mohammadzadeh. 2016. “Financial Viability of Electricity Sectors in Sub-Saharan Africa: Quasi-Fiscal Deficits and Hidden Costs.” Policy Research Working Paper; No. 7788.

- ↑ Ventosa, Mariano; Baı́llo, Álvaro; Ramos, Andrés; Rivier, Michel (2005). "Electricity market modeling trends". Energy Policy 33 (7): 897–913. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2003.10.013.

- ↑ Wood, A.J.; Wollenberg, B.F. (1996). Power Generation, Operation and Control. Wiley.

- ↑ Ruibal, C.M.; Mazumdar, M. (2008). "Forecasting the Mean and the Variance of Electricity Prices in Deregulated Markets". IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 23 (1): 25–32. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2007.913195. ISSN 0885-8950. Bibcode: 2008ITPSy..23...25R.

- ↑ Borgosz-Koczwara, Magdalena; Weron, Aleksander; Wyłomańska, Agnieszka (2009). "Stochastic models for bidding strategies on oligopoly electricity market". Mathematical Methods of Operations Research 69 (3): 579–592. doi:10.1007/s00186-008-0252-7. ISSN 1432-2994.

- ↑ Batlle, Carlos; Barquin, J. (2005). "A strategic production costing model for electricity market price analysis". IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 20 (1): 67–74. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2004.831266. ISSN 0885-8950. Bibcode: 2005ITPSy..20...67B.

- ↑ Guerci, Eric; Ivaldi, Stefano; Cincotti, Silvano (2008). "Learning Agents in an Artificial Power Exchange: Tacit Collusion, Market Power and Efficiency of Two Double-auction Mechanisms". Computational Economics 32 (1–2): 73–98. doi:10.1007/s10614-008-9127-5. ISSN 0927-7099.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Burger, M.; Graeber, B.; Schindlmayr, G. (2007). Managing Energy Risk: An Integrated View on Power and Other Energy Markets. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781119209102. ISBN 9781119209102.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Eydeland, Alexander; Wolyniec, Krzysztof (2003). Energy and Power Risk Management: New Developments in Modeling, Pricing, and Hedging. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-10400-1. http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-0471104000.html.

- ↑ Carmona, René; Coulon, Michael (2014). Benth, Fred Espen. ed. A Survey of Commodity Markets and Structural Models for Electricity Prices. Springer New York. pp. 41–83. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-7248-3_2. ISBN 978-1-4614-7247-6.

- ↑ Weron, Rafał; Zator, Michał (2014). "Revisiting the relationship between spot and futures prices in the Nord Pool electricity market". Energy Economics 44: 178–190. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2014.03.007. http://www.im.pwr.wroc.pl/~hugo/RePEc/wuu/wpaper/HSC_13_08.pdf.

- ↑ Weron, Rafał (2008). "Market price of risk implied by Asian-style electricity options and futures". Energy Economics 30 (3): 1098–1115. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2007.05.004.

- ↑ Benth, Fred Espen; Kiesel, Rüdiger; Nazarova, Anna (2012). "A critical empirical study of three electricity spot price models". Energy Economics 34 (5): 1589–1616. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2011.11.012.

- ↑ Janczura, Joanna; Weron, Rafal (2010). "An empirical comparison of alternate regime-switching models for electricity spot prices". Energy Economics 32 (5): 1059–1073. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2010.05.008. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/20661/1/MPRA_paper_20661.pdf.

- ↑ Benth, Fred Espen; Benth, Jūratė Šaltytė; Koekebakker, Steen (2008). Stochastic Modeling of Electricity and Related Markets. Advanced Series on Statistical Science & Applied Probability. 11. World Scientific. doi:10.1142/6811. ISBN 978-981-281-230-8.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Jonsson, T.; Pinson, P.; Nielsen, H.A.; Madsen, H.; Nielsen, T.S. (2013). "Forecasting Electricity Spot Prices Accounting for Wind Power Predictions". IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Energy 4 (1): 210–218. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2012.2212731. ISSN 1949-3029. Bibcode: 2013ITSE....4..210J.

- ↑ Karakatsani, Nektaria V.; Bunn, Derek W. (2008). "Forecasting electricity prices: The impact of fundamentals and time-varying coefficients". International Journal of Forecasting. Energy Forecasting 24 (4): 764–785. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2008.09.008.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Conejo, Antonio J.; Contreras, Javier; Espínola, Rosa; Plazas, Miguel A. (2005). "Forecasting electricity prices for a day-ahead pool-based electric energy market". International Journal of Forecasting 21 (3): 435–462. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2004.12.005.

- ↑ Weron, Rafał; Misiorek, Adam (2008). "Forecasting spot electricity prices: A comparison of parametric and semiparametric time series models". International Journal of Forecasting. Energy Forecasting 24 (4): 744–763. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2008.08.004.

- ↑ Zareipour, Hamid (2008). Price-based energy management in competitive electricity markets. VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

- ↑ Koopman, Siem Jan; Ooms, Marius; Carnero, M. Angeles (2007). "Periodic Seasonal Reg-ARFIMA–GARCH Models for Daily Electricity Spot Prices". Journal of the American Statistical Association 102 (477): 16–27. doi:10.1198/016214506000001022. ISSN 0162-1459. https://papers.tinbergen.nl/05091.pdf.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Amjady, N. (2006). "Day-ahead price forecasting of electricity markets by a new fuzzy neural network". IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 21 (2): 887–896. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2006.873409. ISSN 0885-8950. Bibcode: 2006ITPSy..21..887A.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Keles, Dogan; Scelle, Jonathan; Paraschiv, Florentina; Fichtner, Wolf (2016). "Extended forecast methods for day-ahead electricity spot prices applying artificial neural networks". Applied Energy 162: 218–230. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.09.087.

- ↑ Rodriguez, C.P.; Anders, G.J. (2004). "Energy price forecasting in the Ontario competitive power system market". IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 19 (1): 366–374. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2003.821470. ISSN 0885-8950. Bibcode: 2004ITPSy..19..366R.

- ↑ Yan, Xing; Chowdhury, Nurul A. (2013). "Mid-term electricity market clearing price forecasting: A hybrid LSSVM and ARMAX approach". International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 53: 20–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2013.04.006.

- ↑ Janczura, Joanna; Trück, Stefan; Weron, Rafał; Wolff, Rodney C. (2013). "Identifying spikes and seasonal components in electricity spot price data: A guide to robust modeling". Energy Economics 38: 96–110. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2013.03.013. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/39277/1/MPRA_paper_39277.pdf.

- ↑ Nowotarski, Jakub; Weron, Rafał (2016). "On the importance of the long-term seasonal component in day-ahead electricity price forecasting". Energy Economics 57: 228–235. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2016.05.009. http://www.im.pwr.wroc.pl/~hugo/RePEc/wuu/wpaper/HSC_16_05.pdf.

- ↑ Nowotarski, Jakub; Tomczyk, Jakub; Weron, Rafał (2013). "Robust estimation and forecasting of the long-term seasonal component of electricity spot prices". Energy Economics 39: 13–27. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2013.04.004. http://www.im.pwr.wroc.pl/~hugo/RePEc/wuu/wpaper/HSC_12_06.pdf.

- ↑ Lisi, Francesco; Nan, Fany (2014). "Component estimation for electricity prices: Procedures and comparisons". Energy Economics 44: 143–159. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2014.03.018.

- ↑ Weron, Rafał; Zator, Michał (2015). "A note on using the Hodrick–Prescott filter in electricity markets". Energy Economics 48: 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2014.11.014. http://www.im.pwr.wroc.pl/~hugo/RePEc/wuu/wpaper/HSC_14_04.pdf.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Gianfreda, Angelica; Grossi, Luigi (2012). "Forecasting Italian electricity zonal prices with exogenous variables". Energy Economics 34 (6): 2228–2239. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2012.06.024.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Ziel, Florian; Steinert, Rick; Husmann, Sven (2015). "Efficient modeling and forecasting of electricity spot prices". Energy Economics 47: 98–111. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2014.10.012.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Amjady, N.; Hemmati, M. (2006). "Energy price forecasting - problems and proposals for such predictions". IEEE Power and Energy Magazine 4 (2): 20–29. doi:10.1109/MPAE.2006.1597990. ISSN 1540-7977.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 Uniejewski, Bartosz; Nowotarski, Jakub; Weron, Rafał (2016-08-05). "Automated Variable Selection and Shrinkage for Day-Ahead Electricity Price Forecasting" (in en). Energies 9 (8): 621. doi:10.3390/en9080621.

- ↑ James, Gareth; Witten, Daniela; Hastie, Trevor; Tibshirani, Robert (2013). An Introduction to Statistical Learning with Applications in R. Springer Texts in Statistics. 103. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-7138-7. ISBN 978-1-4614-7137-0.

- ↑ Karakatsani, Nektaria V.; Bunn, Derek W. (2008). "Forecasting electricity prices: The impact of fundamentals and time-varying coefficients". International Journal of Forecasting. Energy Forecasting 24 (4): 764–785. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2008.09.008.

- ↑ Bessec, Marie; Fouquau, Julien; Meritet, Sophie (2016). "Forecasting electricity spot prices using time-series models with a double temporal segmentation". Applied Economics 48 (5): 361–378. doi:10.1080/00036846.2015.1080801. ISSN 0003-6846. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01502835/document.

- ↑ Barnes, A. K.; Balda, J. C. (2013). Sizing and economic assessment of energy Storage with real-time pricing and ancillary services. 1–7. doi:10.1109/PEDG.2013.6785651. ISBN 978-1-4799-0692-5.

- ↑ Ludwig, Nicole; Feuerriegel, Stefan; Neumann, Dirk (2015). "Putting Big Data analytics to work: Feature selection for forecasting electricity prices using the LASSO and random forests". Journal of Decision Systems 24 (1): 19–36. doi:10.1080/12460125.2015.994290. ISSN 1246-0125.

- ↑ Gaillard, Pierre; Goude, Yannig; Nedellec, Raphaël (2016). "Additive models and robust aggregation for GEFCom2014 probabilistic electric load and electricity price forecasting". International Journal of Forecasting 32 (3): 1038–1050. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2015.12.001.

- ↑ Ziel, F. (2016). "Forecasting Electricity Spot Prices Using Lasso: On Capturing the Autoregressive Intraday Structure". IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 31 (6): 4977–4987. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2016.2521545. ISSN 0885-8950. Bibcode: 2016ITPSy..31.4977Z.

- ↑ De Gooijer, Jan G.; Hyndman, Rob J. (2006). "25 years of time series forecasting". International Journal of Forecasting. Twenty five years of forecasting 22 (3): 443–473. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2006.01.001.

- ↑ Hong, Tao; Pinson, Pierre; Fan, Shu (2014). "Global Energy Forecasting Competition 2012". International Journal of Forecasting 30 (2): 357–363. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2013.07.001.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Nowotarski, Jakub; Weron, Rafał (2015). [Open Access]. "Computing electricity spot price prediction intervals using quantile regression and forecast averaging". Computational Statistics 30 (3): 791–803. doi:10.1007/s00180-014-0523-0. ISSN 0943-4062. http://www.im.pwr.wroc.pl/~hugo/RePEc/wuu/wpaper/HSC_13_12.pdf.

- ↑ Taylor, J W; Majithia, S (2000). "Using combined forecasts with changing weights for electricity demand profiling". Journal of the Operational Research Society 51 (1): 72–82. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jors.2600856.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Bordignon, Silvano; Bunn, Derek W.; Lisi, Francesco; Nan, Fany (2013). "Combining day-ahead forecasts for British electricity prices". Energy Economics. Quantitative Analysis of Energy Markets 35: 88–103. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2011.12.001. http://paduaresearch.cab.unipd.it/8785/1/2011_1_20110110132225.pdf.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Nowotarski, Jakub; Raviv, Eran; Trück, Stefan; Weron, Rafał (2014). "An empirical comparison of alternative schemes for combining electricity spot price forecasts". Energy Economics 46: 395–412. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2014.07.014.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Maciejowska, Katarzyna; Weron, Rafał (2015). [Open Access]. "Forecasting of daily electricity prices with factor models: utilizing intra-day and inter-zone relationships". Computational Statistics 30 (3): 805–819. doi:10.1007/s00180-014-0531-0. ISSN 0943-4062.

- ↑ Raviv, Eran; Bouwman, Kees E.; van Dijk, Dick (2015). "Forecasting day-ahead electricity prices: Utilizing hourly prices". Energy Economics 50: 227–239. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2015.05.014. http://papers.tinbergen.nl/13068.pdf.