| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌeɪrɪˈpɪprəzoʊl/ AIR-i-PIP-rə-zohl Abilify /əˈbɪlɪfaɪ/ ə-BIL-i-fy |

| Trade names | Abilify, others |

| |

| Clinical data | |

| Drug class | Atypical antipsychotic[1] |

| Main uses | Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder[1] |

| Side effects | Vomiting, constipation, sleepiness, dizziness, weight gain, movement disorders[1] |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of use | By mouth (tablets, dissolving tablets, solution); IM (including a depot) |

| Defined daily dose | 13.3 to 15 mg[3] |

| External links | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603012 |

| Legal | |

| License data |

|

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetics | |

| Bioavailability | 87%[4][5][6] |

| Protein binding | >99%[4][5][6] |

| Metabolism | Liver (mostly via CYP3A4 and 2D6[4][5][6]) |

| Elimination half-life | 75 hours (active metabolite is 94 hours)[4][5][6] |

| Excretion | Kidney (27%; <1% unchanged), Faecal (60%; 18% unchanged)[4][5][6] |

| Chemical and physical data | |

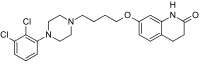

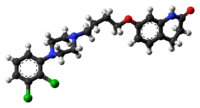

| Formula | C23H27Cl2N3O2 |

| Molar mass | 448.39 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Aripiprazole, sold under the brand name Abilify among others, is an atypical antipsychotic.[1] It is primarily used in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.[1] Other uses include as an add-on treatment in major depressive disorder, tic disorders and irritability associated with autism.[1] It is taken by mouth or injection into a muscle.[1] A Cochrane review found only low quality evidence of effectiveness in treating schizophrenia.[7] Additionally, since many people dropped out of the studies before they were completed, the strength of the conclusions was low.[7]

Common side effects include vomiting, constipation, sleepiness, dizziness, weight gain and movement disorders.[1] Serious side effects may include neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia and anaphylaxis.[1] It is not recommended for older people with dementia-related psychosis due to an increased risk of death.[1] In pregnancy, there is evidence of possible harm to the baby.[1][8] It is not recommended in women who are breastfeeding.[1] It has not been very well studied in people less than 18 years old.[1] The exact mode of action is not entirely clear but may involve effects on dopamine and serotonin.[1]

Aripiprazole was approved for medical use in the United States in 2002.[1] It is available as a generic medication.[9] In the United Kingdom, a month's supply costs the NHS about £2.75 as of 2019.[9] In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is US$10.[10] In 2017, it was the 112th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than six million prescriptions.[11][12] Aripiprazole was discovered in 1988 by scientists at Japanese firm Otsuka Pharmaceutical.[13][14]

Medical uses[edit | edit source]

Aripiprazole is primarily used for the treatment of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.[1][15][6]

Schizophrenia[edit | edit source]

The 2016 NICE guidance for treating psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people recommended aripiprazole as a second line treatment after risperidone for people between 15 and 17 who are having an acute exacerbation or recurrence of psychosis or schizophrenia.[16] A 2014 NICE review of the depot formulation of the drug found that it might have a role in treatment as an alternative to other depot formulations of second generation antipsychotics for people who have trouble taking medication as directed or who prefer it.[17]

A 2014 Cochrane review comparing aripiprazole and other atypical antipsychotics found that it is difficult to determine differences as data quality is poor.[18] A 2011 Cochrane review comparing aripiprazole with placebo concluded that high dropout rates in clinical trials, and a lack of outcome data regarding general functioning, behavior, mortality, economic outcomes, or cognitive functioning make it difficult to definitively conclude that aripiprazole is useful for the prevention of relapse.[7] A Cochrane review found only low quality evidence of effectiveness in treating schizophrenia.[7] Accordingly, part of its methodology on quality of evidence is based on quantity of qualified studies.[19]

A 2013 review found that it is in the middle range of 15 antipsychotics for effectiveness, approximately as effective as haloperidol and quetiapine and slightly more effective than ziprasidone, chlorpromazine, and asenapine, with better tolerability compared to the other antipsychotic drugs (4th best for weight gain, 5th best for extrapyramidal symptoms, best for prolactin elevation, 2nd best for QTc prolongation, and 5th best for sedation). The authors concluded that for acute psychotic episodes aripiprazole results in benefits in some aspects of the condition.[20]

In 2013 the World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry recommended aripiprazole for the treatment of acute exacerbations of schizophrenia as a Grade 1 recommendation and evidence level A.[21]

The British Association for Psychopharmacology similarly recommends that all persons presenting with psychosis receive treatment with an antipsychotic, and that such treatment should continue for at least 1–2 years, as "There is no doubt that antipsychotic discontinuation is strongly associated with relapse during this period". The guideline further notes that "Established schizophrenia requires continued maintenance with doses of antipsychotic medication within the recommended range (Evidence level A)".[22]

The British Association for Psychopharmacology[22] and the World Federation of Societies for Biological Psychiatry suggest that there is little difference in effectiveness between antipsychotics in prevention of relapse, and recommend that the specific choice of antipsychotic be chosen based on each person's preference and side effect profile. The latter group recommends switching to aripiprazole when excessive weight gain is encountered during treatment with other antipsychotics.[21]

Bipolar disorder[edit | edit source]

Aripiprazole is effective for the treatment of acute manic episodes of bipolar disorder in adults, children, and adolescents.[23][24] Used as maintenance therapy, it is useful for the prevention of manic episodes, but is not useful for bipolar depression.[25][26] Thus, it is often used in combination with an additional mood stabilizer; however, co-administration with a mood stabilizer increases the risk of extrapyramidal side effects.[27]

Major depression[edit | edit source]

Aripiprazole is an effective add-on treatment for major depressive disorder; however, there is a greater rate of side effects such as weight gain and movement disorders.[28][29][30][31] The overall benefit is small to moderate and its use appears to neither improve quality of life nor functioning.[29] Aripiprazole may interact with some antidepressants, especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). There are interactions with fluoxetine and paroxetine and lesser interactions with sertraline, escitalopram, citalopram and fluvoxamine, which inhibit CYP2D6, for which aripiprazole is a substrate. CYP2D6 inhibitors increase aripiprazole concentrations to 2-3 times their normal level.[32]

Autism[edit | edit source]

Short-term data (8 weeks) shows reduced irritability, hyperactivity, inappropriate speech, and stereotypy, but no change in lethargic behaviours.[33] Adverse effects include weight gain, sleepiness, drooling and tremors.[33] It is suggested that children and adolescents need to be monitored regularly while taking this medication, to evaluate if this treatment option is still effective after long-term use and note if side effects are worsening. Further studies are needed to understand if this drug is helpful for children after long term use.[33]

Obsessive–compulsive disorder[edit | edit source]

A 2014 systematic review concluded that add-on therapy with low dose aripiprazole is an effective treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder that does not improve with SSRIs alone. The conclusion was based on the results of two relatively small, short-term trials, each of which demonstrated improvements in symptoms.[34] Risperidone (another second-generation antipsychotic) appears to be superior to aripiprazole for this indication, and is recommended by the 2007 American Psychiatric Association guidelines, though aripiprazole is cautiously recommended by a 2017 review by Pignon and colleagues.[35]

Dosage[edit | edit source]

The defined daily dose is 15 mg by mouth or by short acting injection and 13.3 mg by long acting injection.[3]

Side effects[edit | edit source]

In adults, side effects with greater than 10% incidence include weight gain, headache, akathisia, insomnia, and gastro-intestinal effects like nausea and constipation, and lightheadedness.[32][4][5][6][36] Side effects in children are similar, and include sleepiness, increased appetite, and stuffy nose.[32] A strong desire to gamble, binge eat, shop, and have sex may also occur.[37][38]

Uncontrolled movement such as restlessness, tremors, and muscle stiffness may occur.[32]

Discontinuation[edit | edit source]

The British National Formulary recommends a gradual withdrawal when discontinuing antipsychotics to avoid acute withdrawal syndrome or rapid relapse.[39] Symptoms of withdrawal commonly include nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite.[40] Other symptoms may include restlessness, increased sweating, and trouble sleeping.[40] Less commonly there may be a feeling of the world spinning, numbness, or muscle pains.[40] Symptoms generally resolve after a short period of time.[40]

There is tentative evidence that discontinuation of antipsychotics can result in psychosis.[41] It may also result in reoccurrence of the condition that is being treated.[42] Rarely tardive dyskinesia can occur when the medication is stopped.[40]

Overdose[edit | edit source]

Children or adults who ingested acute overdoses have usually manifested central nervous system depression ranging from mild sedation to coma; serum concentrations of aripiprazole and dehydroaripiprazole in these people were elevated by up to 3-4 fold over normal therapeutic levels; as of 2008 no deaths had been recorded.[43][44]

Interactions[edit | edit source]

Aripiprazole is a substrate of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Coadministration with medications that inhibit (e.g. paroxetine, fluoxetine) or induce (e.g. carbamazepine) these metabolic enzymes are known to increase and decrease, respectively, plasma levels of aripiprazole.[45] As such, anyone taking aripiprazole should be aware that their dosage of aripiprazole may need to be adjusted.

Precautions should be taken in people with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus who are started on atypical antipsychotics along with other medications that affect blood sugar levels and should be monitored regularly for worsening of glucose control. The liquid form (oral solution) of this medication may contain up to 15 grams of sugar per dose.[1]

Antipsychotics like aripiprazole and stimulant medications, such as amphetamine, are traditionally thought to have opposing effects to their effects on dopamine receptors: stimulants are thought to increase dopamine in the synaptic cleft, whereas antipsychotics are thought to decrease dopamine. However, it is an oversimplification to state the interaction as such, due to the differing actions of antipsychotics and stimulants in different parts of the brain, as well as the effects of antipsychotics on non-dopaminergic receptors. This interaction frequently occurs in the setting of comorbid ADHD (for which stimulants are commonly prescribed) and off-label treatment of aggression with antipsychotics. Aripiprazole has shown some benefit in improving cognitive functioning in people with ADHD without other psychiatric comorbidities, though the results have been disputed. The combination of antipsychotics like aripiprazole with stimulants should not be considered an absolute contraindication.[46]

Pharmacology[edit | edit source]

Pharmacodynamics[edit | edit source]

| Site | Ki (nM) | Action | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 1.7–5.6 | Partial agonist | [48][49][50] |

| 5-HT1B | 830 | ND | [48] |

| 5-HT1D | 68 | ND | [48] |

| 5-HT1E | 8,000 | ND | [48] |

| 5-HT2A | 3.4–35 | Antagonist | [50][48][49] |

| 5-HT2B | 0.11-0.36 | Inverse agonist | [48] |

| 5-HT2C | 15–180 | Partial agonist | [50][48][49] |

| 5-HT3 | 628 | ND | [48] |

| 5-HT5A | 1,240 | ND | [48] |

| 5-HT6 | 214–786 | Antagonist | [50][48][49] |

| 5-HT7 | 9.6–39 | Antagonist | [48][49][50] |

| D1 | 265–1,170 | ND | [48] |

| D2 | 0.34 | Partial agonist | [51][49][48] |

| D2L | 0.74–0.9 | Partial agonist | [48] |

| D3 | 0.8–9.7 | Partial agonist | [50][48] |

| D4 | 44–514 | Partial agonist | [50][48] |

| D5 | 95–2,590 | ND | [50][48] |

| α1A | 25.9 | ND | [48][49] |

| α1B | 34.4 | ND | [48] |

| α2A | 74.3 | ND | [48][49] |

| α2B | 102 | ND | [48][49] |

| α2C | 37.9 | ND | [48][49] |

| β1 | 141 | ND | [48] |

| β2 | 163 | ND | [48] |

| H1 | 27.9–61 | ND | [48][49][50] |

| H2 | >10,000 | ND | [48] |

| H3 | 224 | ND | [48] |

| H4 | >10,000 | ND | [48] |

| M1 | 6,780 | ND | [48] |

| M2 | 3,510 | ND | [48] |

| M3 | 4,680 | ND | [48][49] |

| M4 | 1,520 | ND | [48] |

| M5 | 2,330 | ND | [48] |

| SERT | 98–1,080 | Blocker | [50][48] |

| NET | 2,090 | Blocker | [48] |

| DAT | 3,220 | Blocker | [48] |

| NMDA (PCP) |

4,001 | Antagonist | [48] |

| Values are Ki (nM). The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug binds to the site. All data are for human cloned proteins, except 5-HT3 (rat), D4 (human/rat), H3 (guinea pig), and NMDA/PCP (rat).[48] | |||

Aripiprazole's mechanism of action is different from those of the other FDA-approved atypical antipsychotics (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and risperidone).[52][53][54][55] It shows differential engagement at the dopamine receptor (D2[48]). It appears to show predominantly antagonist activity on postsynaptic D2 receptors and partial agonist activity on presynaptic D2 receptors,[56] D3,[48][57][58] and partially D4[48][53]) and is a partial activator of serotonin (5-HT1A,[48][59][60] 5-HT2A,[48] 5-HT2B,[48] 5-HT6, and 5-HT7).[48][55] It also shows lower and likely insignificant effect on histamine (H1), epinephrine/norepinephrine (α), and otherwise dopamine (D4), as well as the serotonin transporter.[48][53] Aripiprazole acts by modulating neurotransmission overactivity of dopamine, which is thought to mitigate schizophrenia symptoms.[61]

It appears to show predominantly antagonist activity on postsynaptic D2 receptors and partial agonist activity on presynaptic D2 receptors.[56] Aripiprazole is also a partial agonist of the D3 receptor.[48] In healthy human volunteers, D2 and D3 receptor occupancy levels are high, with average levels ranging between approximately 71% at 2 mg/day to approximately 96% at 40 mg/day.[57][58] Most atypical antipsychotics bind preferentially to extrastriatal receptors, but aripiprazole appears to be less preferential in this regard, as binding rates are high throughout the brain.[62]

Aripiprazole is also a partial agonist of the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor (intrinsic activity = 68%).[48][59][60] It is a very weak partial agonist of the 5-HT2A receptor (intrinsic activity = 12.7%),[48] and like other atypical antipsychotics, displays a functional antagonist profile at this receptor.[48] The drug differs from other atypical antipsychotics in having higher affinity for the D2 receptor than for the 5-HT2A receptor.[60] At the 5-HT2B receptor, aripiprazole acts as a potent inverse agonist.[48] Unlike other antipsychotics, aripiprazole is a high-efficacy partial agonist of the 5-HT2C receptor (intrinsic activity = 82%) and with relatively weak affinity;[48] this property may underlie the minimal weight gain seen in the course of therapy.[63] At the 5-HT7 receptor, aripiprazole is a very weak partial agonist with barely measurable intrinsic activity, and hence is a functional antagonist of this receptor.[48][55] Aripiprazole also shows lower but likely clinically insignificant affinity for a number of other sites, such as the histamine H1, α-adrenergic, and dopamine D4 receptors as well as the serotonin transporter, while it has negligible affinity for the muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.[48][53]

Since the actions of aripiprazole differ markedly across receptor systems aripiprazole was sometimes an antagonist (e.g. at 5-HT6 and D2L), sometimes an inverse agonist (e.g. 5-HT2B), sometimes a partial agonist (e.g. D2L), and sometimes a full agonist (D3, D4). Aripiprazole was frequently found to be a partial agonist, with an intrinsic activity that could be low (D2L, 5-HT2A, 5-HT7), intermediate (5-HT1A), or high (D4, 5-HT2C). This mixture of agonist actions at D2-dopamine receptors is consistent with the hypothesis that aripiprazole has ‘functionally selective’ actions.[64] The ‘functional-selectivity’ hypothesis proposes that a mixture of agonist/partial agonist/antagonist actions are likely. According to this hypothesis, agonists may induce structural changes in receptor conformations that are differentially ‘sensed’ by the local complement of G proteins to induce a variety of functional actions depending upon the precise cellular milieu. The diverse actions of aripiprazole at D2-dopamine receptors are clearly cell-type specific (e.g. agonism, antagonism, partial agonism), and are most parsimoniously explained by the ‘functional selectivity’ hypothesis.[48]

Since 5-HT2C receptors have been implicated in the control of depression, OCD, and appetite, agonism at the 5-HT2C receptor might be associated with therapeutic potential in obsessive compulsive disorder, obesity, and depression. 5-HT2C agonism has been demonstrated to induce anorexia via enhancement of serotonergic neurotransmission via activation of 5-HT2C receptors; it is conceivable that the 5-HT2C agonist actions of aripiprazole may, thus, be partly responsible for the minimal weight gain associated with this compound in clinical trials. In terms of potential action as an antiobsessional agent, it is worthwhile noting that a variety of 5-HT2A/5-HT2C agonists have shown promise as antiobsessional agents, yet many of these compounds are hallucinogenic, presumably due to 5-HT2A activation. Aripiprazole has a favorable pharmacological profile in being a 5-HT2A antagonist and a 5-HT2C partial agonist. Based on this profile, one can predict that aripiprazole may have antiobsessional and anorectic actions in humans.[48]

Wood and Reavill's (2007) review of published and unpublished data proposed that, at therapeutically relevant doses, aripiprazole may act essentially as a selective partial agonist of the D2 receptor without significantly affecting the majority of serotonin receptors.[56] A positron emission tomography imaging study found that 10 to 30 mg/day aripiprazole resulted in 85 to 95% occupancy of the D2 receptor in various brain areas (putamen, caudate, ventral striatum) versus 54 to 60% occupancy of the 5-HT2A receptor and only 16% occupancy of the 5-HT1A receptor.[65][60] It has been suggested that the low occupancy of the 5-HT1A receptor by aripiprazole may have been an erroneous measurement however.[66]

Aripiprazole acts by modulating neurotransmission overactivity on the dopaminergic mesolimbic pathway, which is thought to be a cause of positive schizophrenia symptoms.[61] Due to its agonist activity on D2 receptors, aripiprazole may also increase dopaminergic activity to optimal levels in the mesocortical pathways where it is reduced.[61]

Pharmacokinetics[edit | edit source]

Aripiprazole displays linear kinetics and has an elimination half-life of approximately 75 hours. Steady-state plasma concentrations are achieved in about 14 days. Cmax (maximum plasma concentration) is achieved 3–5 hours after oral dosing. Bioavailability of the oral tablets is about 90% and the drug undergoes extensive hepatic metabolization (dehydrogenation, hydroxylation, and N-dealkylation), principally by the enzymes CYP2D6 and CYP3A4. Its only known active metabolite is dehydro-aripiprazole, which typically accumulates to approximately 40% of the aripiprazole concentration. The parenteral drug is excreted only in traces, and its metabolites, active or not, are excreted via feces and urine.[53] When dosed daily, brain concentrations of aripiprazole will increase for a period of 10–14 days, before reaching stable constant levels.[citation needed]

| Medication | Brand name | Class | Vehicle | Dosage | Tmax | t1/2 single | t1/2 multiple | logPc | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole lauroxil | Aristada | Atypical | Watera | 441–1064 mg/4–8 weeks | 24–35 days | ? | 54–57 days | 7.9–10.0 | |

| Aripiprazole monohydrate | Abilify Maintena | Atypical | Watera | 300–400 mg/4 weeks | 7 days | ? | 30–47 days | 4.9–5.2 | |

| Bromperidol decanoate | Impromen Decanoas | Typical | Sesame oil | 40–300 mg/4 weeks | 3–9 days | ? | 21–25 days | 7.9 | [67] |

| Clopentixol decanoate | Sordinol Depot | Typical | Viscoleob | 50–600 mg/1–4 weeks | 4–7 days | ? | 19 days | 9.0 | [68] |

| Flupentixol decanoate | Depixol | Typical | Viscoleob | 10–200 mg/2–4 weeks | 4–10 days | 8 days | 17 days | 7.2–9.2 | [68][69] |

| Fluphenazine decanoate | Prolixin Decanoate | Typical | Sesame oil | 12.5–100 mg/2–5 weeks | 1–2 days | 1–10 days | 14–100 days | 7.2–9.0 | [70][71][72] |

| Fluphenazine enanthate | Prolixin Enanthate | Typical | Sesame oil | 12.5–100 mg/1–4 weeks | 2–3 days | 4 days | ? | 6.4–7.4 | [71] |

| Fluspirilene | Imap, Redeptin | Typical | Watera | 2–12 mg/1 week | 1–8 days | 7 days | ? | 5.2–5.8 | [73] |

| Haloperidol decanoate | Haldol Decanoate | Typical | Sesame oil | 20–400 mg/2–4 weeks | 3–9 days | 18–21 days | 7.2–7.9 | [74][75] | |

| Olanzapine pamoate | Zyprexa Relprevv | Atypical | Watera | 150–405 mg/2–4 weeks | 7 days | ? | 30 days | – | |

| Oxyprothepin decanoate | Meclopin | Typical | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | 8.5–8.7 | |

| Paliperidone palmitate | Invega Sustenna | Atypical | Watera | 39–819 mg/4–12 weeks | 13–33 days | 25–139 days | ? | 8.1–10.1 | |

| Perphenazine decanoate | Trilafon Dekanoat | Typical | Sesame oil | 50–200 mg/2–4 weeks | ? | ? | 27 days | 8.9 | |

| Perphenazine enanthate | Trilafon Enanthate | Typical | Sesame oil | 25–200 mg/2 weeks | 2–3 days | ? | 4–7 days | 6.4–7.2 | [76] |

| Pipotiazine palmitate | Piportil Longum | Typical | Viscoleob | 25–400 mg/4 weeks | 9–10 days | ? | 14–21 days | 8.5–11.6 | [69] |

| Pipotiazine undecylenate | Piportil Medium | Typical | Sesame oil | 100–200 mg/2 weeks | ? | ? | ? | 8.4 | |

| Risperidone | Risperdal Consta | Atypical | Microspheres | 12.5–75 mg/2 weeks | 21 days | ? | 3–6 days | – | |

| Zuclopentixol acetate | Clopixol Acuphase | Typical | Viscoleob | 50–200 mg/1–3 days | 1–2 days | 1–2 days | 4.7–4.9 | ||

| Zuclopentixol decanoate | Clopixol Depot | Typical | Viscoleob | 50–800 mg/2–4 weeks | 4–9 days | ? | 11–21 days | 7.5–9.0 | |

| Note: All by intramuscular injection. Footnotes: a = Microcrystalline or nanocrystalline aqueous suspension. b = Low-viscosity vegetable oil (specifically fractionated coconut oil with medium-chain triglycerides). c = Predicted, from PubChem and DrugBank. Sources: Main: See template. | |||||||||

Chemistry[edit | edit source]

Aripiprazole is a phenylpiperazine and is chemically related to nefazodone, etoperidone, and trazodone.[77][78]

History[edit | edit source]

Aripiprazole was discovered by scientists at Otsuka Pharmaceutical and was called OPC-14597.[13][79] It was first published in 1995.[79][80] Otsuka initially developed the drug, and partnered with Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) in 1999 to complete development, obtain approvals, and market aripiprazole.[81]

It was approved by the FDA for schizophrenia on November 15, 2002 and the European Medicines Agency on 4 June 2004; for acute manic and mixed episodes associated with bipolar disorder on October 1, 2004; as an adjunct for major depressive disorder on November 20, 2007;[82] and to treat irritability in children with autism on 20 November 2009.[83] Likewise it was approved for use as a treatment for schizophrenia by the TGA of Australia in May 2003.[32]

Aripiprazole has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of both acute manic and mixed episodes, in people older than 10 years.[84]

In 2006, the FDA required the companies to add a black box warning to the label, warning that older people who were given the drug for dementia-related psychosis were at greater risk of death.[85]

In 2007, aripiprazole was approved by the FDA for the treatment of unipolar depression when used adjunctively with an antidepressant medication.[86] That same year, BMS settled a case with the U.S. government in which it paid $515 million; the case covered several drugs but the focus was on BMS's off-label marketing of aripiprazole for children and older people with dementia.[87]

In 2011 Otsuka and Lundbeck signed a collaboration to develop a depot formulation of apripiprazole.[88]

As of 2013, Abilify had annual sales of US$7 billion.[89] In 2013 BMS returned marketing rights to Otsuka, but kept manufacturing the drug.[90] Also in 2013, Otsuka and Lundbeck received U.S. and European marketing approval for an injectable depot formulation of aripiprazole.[91][92]

Otsuka's U.S. patent on aripiprazole expired on October 20, 2014 but due to a pediatric extension, a generic did not become available until April 20, 2015.[84] Barr Laboratories (now Teva Pharmaceuticals) initiated a patent challenge under the Hatch-Waxman Act in March 2007.[93] On November 15, 2010, this challenge was rejected by the U.S. District Court in New Jersey.[94]

Otsuka's European patent EP0367141 which would have expired on 26 October 2009, was extended by a Supplementary Protection Certificate (SPC) to 26 October 2014.,[95] The UK Intellectual Property Office decided[96] on 4 March 2015 that the SPC could not be further extended by six months under Regulation (EC) No 1901/2006. Even if the decision is successfully appealed, protection in Europe will not extend beyond 26 April 2015.

From April 2013 to March 2014, sales of Abilify amounted to almost $6.9 billion.[97]

In April 2015, the FDA announced the first generic versions.[98][99] In October 2015, aripiprazole lauroxil, a prodrug of aripiprazole that is administered via intramuscular injection once every four to six weeks for the treatment of schizophrenia, was approved by the FDA.[100][101]

In 2016, BMS settled cases with 42 U.S. states that had charged BMS with off-label marketing to older people with dementia; BMS agreed to pay $19.5 million.[85][102]

In November 2017, the FDA approved Abilify MyCite, a digital pill containing a sensor intended to record when its consumer takes their medication.[103][104]

Society and culture[edit | edit source]

Cost[edit | edit source]

In the United States, the wholesale cost of this amount is US$10.[10] In 2017, it was the 112th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than six million prescriptions.[11][12]

Regulatory status[edit | edit source]

| Regulatory administration (country)[105][106][107] | Schizophrenia | Acute mania | Bipolar maintenance | Major depressive disorder (as an adjunct) | Irritability in autism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food and Drug Administration (US) | Yes | Yes | Yes (as an adjunct to lithium/valproate) | Yes | Yes (children and adolescents) |

| Therapeutic Goods Administration (AU) | Yes | Yes (as an adjunct to lithium/valproate) | Yes | No | No |

| Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (UK) | Yes | Yes | Yes (to prevent mania) | No | No |

Research[edit | edit source]

Urine drug screens are used to test for recreational drug use. There are case reports of 2 children accidentally ingesting large quantities of aripiprazole and subsequently testing positive for amphetamines on urine drug screens; both children then had gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis sent on their blood and urine that were negative for amphetamines.[108]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 "Aripiprazole, ARIPiprazole Lauroxil Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Aripiprazole Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 22 August 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "WHOCC - ATC/DDD Index". www.whocc.no. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 "Abilify (aripiprazole) tablet Abilify (aripiprazole) solution Abilify Discmelt (aripiprazole) tablet, orally disintegrating Abilify (aripiprazole) injection, solution [Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.]". DailyMed. Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc. April 2013. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 "Abilify Tablets, Orodispersible Tablets, Oral Solution - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Otsuka Pharmaceuticals (UK) Ltd. 20 September 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 "ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Otsuka Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Belgamwar RB, El-Sayeh HG (August 2011). "Aripiprazole versus placebo for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD006622. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006622.pub2. PMID 21833956.

- ↑ "Prescribing medicines in pregnancy database". Australian Government. 3 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 British national formulary: BNF 76 (76th ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 392. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "NADAC as of 2019-02-20". Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Archived from the original on 2019-02-26. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Aripiprazole - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Aripiprazole". AdisInsight. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ↑ Behere, Prakash B.; Das, Anweshak; Behere, Aniruddh P. (2018). Clinical Psychopharmacology: An Update. Springer. p. 66. ISBN 9789811320927. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ "FDA prescribing information aripiprazole" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-06-16. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ↑ "Psychosis and schizophrenia in children and young people: recognition and management | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". NICE. October 2016. Archived from the original on 2020-06-22. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ "Schizophrenia: aripiprazole prolonged-release suspension for injection | Guidance and guidelines | NICE". NICE. 24 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ↑ Khanna P, Suo T, Komossa K, Ma H, Rummel-Kluge C, El-Sayeh HG, Leucht S, Xia J (January 2014). "Aripiprazole versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD006569. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006569.pub5. PMC 4164478. PMID 24385408.

- ↑ "Levels of Evidence". Cochrane. Cochrane. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ↑ Leucht S, Cipriani A, Spineli L, Mavridis D, Orey D, Richter F, Samara M, Barbui C, Engel RR, Geddes JR, Kissling W, Stapf MP, Lässig B, Salanti G, Davis JM (September 2013). "Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis". Lancet. 382 (9896): 951–62. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. PMID 23810019.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J, Glenthoj B, Gattaz WF, Thibaut F, Möller HJ (February 2013). "World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 2: update 2012 on the long-term treatment of schizophrenia and management of antipsychotic-induced side effects". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 14 (1): 2–44. doi:10.3109/15622975.2012.739708. PMID 23216388.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Barnes TR (May 2011). "Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (5): 567–620. doi:10.1177/0269881110391123. PMID 21292923.

- ↑ "Bipolar disorder: assessment and management". Recommendations; Guidance and guidelines. UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Archived from the original on 2020-08-06. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

1.1 Care for adults, children and young people across all phases of bipolar disorder

- ↑ Brown R, Taylor MJ, Geddes J (December 2013). "Aripiprazole alone or in combination for acute mania". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD005000. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005000.pub2. PMID 24346956. Archived from the original on 2020-06-23. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ De Fruyt J, Deschepper E, Audenaert K, Constant E, Floris M, Pitchot W, Sienaert P, Souery D, Claes S (May 2012). "Second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 26 (5): 603–17. doi:10.1177/0269881111408461. PMID 21940761. Archived from the original on 2021-08-27. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ Gitlin M, Frye MA (May 2012). "Maintenance therapies in bipolar disorders". Bipolar Disorders. 14 Suppl 2: 51–65. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00992.x. PMID 22510036.

- ↑ de Bartolomeis A, Perugi G (October 2012). "Combination of aripiprazole with mood stabilizers for the treatment of bipolar disorder: from acute mania to long-term maintenance". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 13 (14): 2027–36. doi:10.1517/14656566.2012.719876. PMID 22946707.

- ↑ Komossa K, Depping AM, Gaudchau A, Kissling W, Leucht S (December 2010). "Second-generation antipsychotics for major depressive disorder and dysthymia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008121. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008121.pub2. PMID 21154393.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Spielmans GI, Berman MI, Linardatos E, Rosenlicht NZ, Perry A, Tsai AC (Mar 12, 2013). "Adjunctive atypical antipsychotic treatment for major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of depression, quality of life, and safety outcomes". PLOS Medicine. 10 (3): e1001403. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001403. PMC 3595214. PMID 23554581.

- ↑ Nelson JC, Papakostas GI (September 2009). "Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 166 (9): 980–91. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030312. PMID 19687129.

- ↑ Komossa K, Depping AM, Gaudchau A, Kissling W, Leucht S (December 2010). "Second-generation antipsychotics for major depressive disorder and dysthymia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): CD008121. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008121.pub2. PMID 21154393.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 "Product Information for Abilify Aripiprazole Tablets & Orally Disintegrating Tablets". TGA eBusiness Services. Bristol-Myers Squibb Australia Pty Ltd. 1 November 2012. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Hirsch LE, Pringsheim T (June 2016). "Aripiprazole for autism spectrum disorders (ASD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD009043. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009043.pub3. PMC 7120220. PMID 27344135.

- ↑ Veale D, Miles S, Smallcombe N, Ghezai H, Goldacre B, Hodsoll J (November 2014). "Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in SSRI treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Psychiatry. 14 (1): 317. doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0317-5. PMC 4262998. PMID 25432131.

- ↑ Pignon, Baptiste; Tezenas du Montcel, Chloé; Carton, Louise; Pelissolo, Antoine (7 November 2017). "The Place of Antipsychotics in the Therapy of Anxiety Disorders and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders". Current Psychiatry Reports. 19 (12): 103. doi:10.1007/s11920-017-0847-x. PMID 29110139.

- ↑ "Abilify Discmelt, Abilify Maintena (aripiprazole) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ "Aripiprazole (Abilify, Abilify Maintena, Aristada): Drug Safety Communication - FDA Warns About New Impulse-control Problems". FDA. 3 May 2016. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ↑ Grall-Bronnec M, Sauvaget A, Perrouin F, Leboucher J, Etcheverrigaray F, Challet-Bouju G, Gaboriau L, Derkinderen P, Jolliet P, Victorri-Vigneau C (2016). "Pathological Gambling Associated With Aripiprazole or Dopamine Replacement Therapy: Do Patients Share the Same Features? A Review". J Clin Psychopharmacol. 36 (1): 63–70. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000444. PMC 4700874. PMID 26658263.

- ↑ Joint Formulary Committee, BMJ, ed. (March 2009). "4.2.1". British National Formulary (57 ed.). United Kingdom: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-85369-845-6.

Withdrawal of antipsychotic drugs after long-term therapy should always be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or rapid relapse.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 40.4 Haddad, Peter; Haddad, Peter M.; Dursun, Serdar; Deakin, Bill (2004). Adverse Syndromes and Psychiatric Drugs: A Clinical Guide. OUP Oxford. pp. 207–216. ISBN 9780198527480. Archived from the original on 2021-04-22. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ Moncrieff J (July 2006). "Does antipsychotic withdrawal provoke psychosis? Review of the literature on rapid onset psychosis (supersensitivity psychosis) and withdrawal-related relapse". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 114 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00787.x. PMID 16774655.

- ↑ Sacchetti, Emilio; Vita, Antonio; Siracusano, Alberto; Fleischhacker, Wolfgang (2013). Adherence to Antipsychotics in Schizophrenia. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 85. ISBN 9788847026797. Archived from the original on 2021-04-22. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ Baselt, Randall C. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 105–6. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ↑ Skov L, Johansen SS, Linnet K (Jan 2015). "Postmortem Femoral Blood Reference Concentrations of Aripiprazole, Chlorprothixene, and Quetiapine". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 39 (1): 41–4. doi:10.1093/jat/bku121. PMID 25342720.

- ↑ "Abilify (Aripiprazole) - Warnings and Precautions". DrugLib.com. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ↑ Yanofski, J (June 2010). "The dopamine dilemma: using stimulants and antipsychotics concurrently". Psychiatry (Edgmont (Pa. : Township)). 7 (6): 18–23. PMC 2898838. PMID 20622942.

- ↑ Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ 48.00 48.01 48.02 48.03 48.04 48.05 48.06 48.07 48.08 48.09 48.10 48.11 48.12 48.13 48.14 48.15 48.16 48.17 48.18 48.19 48.20 48.21 48.22 48.23 48.24 48.25 48.26 48.27 48.28 48.29 48.30 48.31 48.32 48.33 48.34 48.35 48.36 48.37 48.38 48.39 48.40 48.41 48.42 48.43 48.44 48.45 48.46 48.47 48.48 48.49 48.50 48.51 48.52 48.53 48.54 48.55 48.56 Shapiro DA, Renock S, Arrington E, Chiodo LA, Liu LX, Sibley DR, Roth BL, Mailman R (2003). "Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a unique and robust pharmacology". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (8): 1400–11. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300203. PMID 12784105.

- ↑ 49.00 49.01 49.02 49.03 49.04 49.05 49.06 49.07 49.08 49.09 49.10 49.11 Kroeze WK, Hufeisen SJ, Popadak BA, Renock SM, Steinberg S, Ernsberger P, Jayathilake K, Meltzer HY, Roth BL (2003). "H1-histamine receptor affinity predicts short-term weight gain for typical and atypical antipsychotic drugs". Neuropsychopharmacology. 28 (3): 519–26. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1300027. PMID 12629531.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 50.6 50.7 50.8 50.9 Keck PE, McElroy SL (2003). "Aripiprazole: a partial dopamine D2 receptor agonist antipsychotic". Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 12 (4): 655–62. doi:10.1517/13543784.12.4.655. PMID 12665420.

- ↑ Kurahashi, N.; McQuade, R.; Burris, K.D.; Jordan, S.; Tottori, K.; Kikuchi, T. (2003). "Aripiprazole: A dopamine-serotonin system stabilizer". Schizophrenia Research. 60 (1): 312–313. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(03)80255-4. ISSN 0920-9964.

- ↑ Starrenburg FC, Bogers JP (April 2009). "How can antipsychotics cause Diabetes Mellitus? Insights based on receptor-binding profiles, humoral factors and transporter proteins". European Psychiatry. 24 (3): 164–70. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2009.01.001. PMID 19285836.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 "Abilify (Aripiprazole) - Clinical Pharmacology". DrugLib.com. 14 February 2007. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ↑ Brunton, Laurence (2011). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 12th Edition. China: McGraw-Hill. pp. 406–410. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Davies MA, Sheffler DJ, Roth BL (2004). "Aripiprazole: a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a uniquely robust pharmacology". CNS Drug Reviews. 10 (4): 317–36. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00030.x. PMC 6741761. PMID 15592581.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Wood M, Reavill C (2007). "Aripiprazole acts as a selective dopamine D2 receptor partial agonist". Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 16 (6): 771–5. doi:10.1517/13543784.16.6.771. PMID 17501690.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Kegeles LS, Slifstein M, Frankle WG, Xu X, Hackett E, Bae SA, Gonzales R, Kim JH, Alvarez B, Gil R, Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A (December 2008). "Dose-occupancy study of striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors by aripiprazole in schizophrenia with PET and [18F]fallypride". Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (13): 3111–25. doi:10.1038/npp.2008.33. PMID 18418366.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Yokoi F, Gründer G, Biziere K, Stephane M, Dogan AS, Dannals RF, Ravert H, Suri A, Bramer S, Wong DF (August 2002). "Dopamine D2 and D3 receptor occupancy in normal humans treated with the antipsychotic drug aripiprazole (OPC 14597): a study using positron emission tomography and [11C]raclopride". Neuropsychopharmacology. 27 (2): 248–59. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00304-4. PMID 12093598.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Jordan S, Koprivica V, Chen R, Tottori K, Kikuchi T, Altar CA (April 2002). "The antipsychotic aripiprazole is a potent, partial agonist at the human 5-HT1A receptor". European Journal of Pharmacology. 441 (3): 137–40. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(02)01532-7. PMID 12063084.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 Mamo D, Graff A, Mizrahi R, Shammi CM, Romeyer F, Kapur S (2007). "Differential effects of aripiprazole on D(2), 5-HT(2), and 5-HT(1A) receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia: a triple tracer PET study". Am J Psychiatry. 164 (9): 1411–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091479. PMID 17728427.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Mailman RB, Murthy V (May 2010). "Third generation antipsychotic drugs: partial agonism or receptor functional selectivity?". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 16 (5): 488–501. doi:10.2174/138161210790361461. PMC 2958217. PMID 19909227.

- ↑ "In This Issue". Am J Psychiatry. 165 (8): A46. August 2008. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.165.8.A46.

- ↑ Zhang JY, Kowal DM, Nawoschik SP, Lou Z, Dunlop J (February 2006). "Distinct functional profiles of aripiprazole and olanzapine at RNA edited human 5-HT2C receptor isoforms". Biochemical Pharmacology. 71 (4): 521–9. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2005.11.007. PMID 16336943.

- ↑ Lawler, C. P.; Prioleau, C.; Lewis, M. M.; Mak, C.; Jiang, D.; Schetz, J. A.; Gonzalez, A. M.; Sibley, D. R.; Mailman, R. B. (June 1999). "Interactions of the novel antipsychotic aripiprazole (OPC-14597) with dopamine and serotonin receptor subtypes". Neuropsychopharmacology. 20 (6): 612–627. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00099-2. ISSN 0893-133X. PMID 10327430.

- ↑ Mauri MC, Paletta S, Maffini M, Colasanti A, Dragogna F, Di Pace C, Altamura AC (2014). "Clinical pharmacology of atypical antipsychotics: an update". Excli J. 13: 1163–91. PMC 4464358. PMID 26417330.

- ↑ Kessler RM (2007). "Aripiprazole: what is the role of dopamine D(2) receptor partial agonism?". Am J Psychiatry. 164 (9): 1310–2. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071043. PMID 17728411.

- ↑ Parent M, Toussaint C, Gilson H (1983). "Long-term treatment of chronic psychotics with bromperidol decanoate: clinical and pharmacokinetic evaluation". Current Therapeutic Research. 34 (1): 1–6.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Jørgensen A, Overø KF (1980). "Clopenthixol and flupenthixol depot preparations in outpatient schizophrenics. III. Serum levels". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 279: 41–54. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1980.tb07082.x. PMID 6931472.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Reynolds JE (1993). "Anxiolytic sedatives, hypnotics and neuroleptics.". Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia (30th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. pp. 364–623.

- ↑ Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW, Davis CM, Richards A, Seidel DR (May 1984). "Future of depot neuroleptic therapy: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic approaches". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 45 (5 Pt 2): 50–9. PMID 6143748.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Curry SH, Whelpton R, de Schepper PJ, Vranckx S, Schiff AA (April 1979). "Kinetics of fluphenazine after fluphenazine dihydrochloride, enanthate and decanoate administration to man". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 7 (4): 325–31. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1979.tb00941.x. PMC 1429660. PMID 444352.

- ↑ Young D, Ereshefsky L, Saklad SR, Jann MW, Garcia N (1984). Explaining the pharmacokinetics of fluphenazine through computer simulations. (Abstract.). 19th Annual Midyear Clinical Meeting of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. Dallas, Texas.

- ↑ Janssen PA, Niemegeers CJ, Schellekens KH, Lenaerts FM, Verbruggen FJ, van Nueten JM, et al. (November 1970). "The pharmacology of fluspirilene (R 6218), a potent, long-acting and injectable neuroleptic drug". Arzneimittel-Forschung. 20 (11): 1689–98. PMID 4992598.

- ↑ Beresford R, Ward A (January 1987). "Haloperidol decanoate. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in psychosis". Drugs. 33 (1): 31–49. doi:10.2165/00003495-198733010-00002. PMID 3545764.

- ↑ Reyntigens AJ, Heykants JJ, Woestenborghs RJ, Gelders YG, Aerts TJ (1982). "Pharmacokinetics of haloperidol decanoate. A 2-year follow-up". International Pharmacopsychiatry. 17 (4): 238–46. doi:10.1159/000468580. PMID 7185768.

- ↑ Larsson M, Axelsson R, Forsman A (1984). "On the pharmacokinetics of perphenazine: a clinical study of perphenazine enanthate and decanoate". Current Therapeutic Research. 36 (6): 1071–88.

- ↑ Akritopoulou-Zanze, Irini (2012). "6. Arylpiperazine-Based 5-HT1A Receptor Partial Agonists and 5-HT2A Antagonists for the Treatment of Autism, Depression, Anxiety, Psychosis, and Schizophrenia". In Dinges, Jürgen; Lamberth, Clemens (eds.). Bioactive heterocyclic compound classes pharmaceuticals. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-66445-0.

- ↑ Dörwald, Florencioa Zaragoza, ed. (2012). "46. Arylalkylamines". Lead optimization for medicinal chemists: pharmacokinetic properties of functional groups and organic compounds. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-64564-0.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Grady, MA; Gasperoni, TL; Kirkpatrick, P (June 2003). "Aripiprazole". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 2 (6): 427–8. doi:10.1038/nrd1114. PMID 12790153.

- ↑ Kikuchi, T; Tottori, K; Uwahodo, Y; Hirose, T; Miwa, T; Oshiro, Y; Morita, S (July 1995). "7-(4-[4-(2,3-Dichlorophenyl)-1-piperazinyl]butyloxy)-3,4-dihydro-2(1H)-quinolinone (OPC-14597), a new putative antipsychotic drug with both presynaptic dopamine autoreceptor agonistic activity and postsynaptic D2 receptor antagonistic activity". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 274 (1): 329–36. PMID 7616416.

- ↑ "B-MS reveals Ph III aripiprazole data - Pharmaceutical industry news". The Pharma Letter. 17 May 2000. Archived from the original on 27 January 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ↑ Hitti, Miranda (20 November 2007). "FDA OKs Abilify for Depression". WebMD. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ↑ Keating, Gina (23 November 2009). "FDA OKs Abilify for child autism irritability". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 "Patent and Exclusivity Search Results". Electronic Orange Book. US Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 4 May 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2008.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Mitchell, Max (December 8, 2016). "Bristol-Myers Squibb Agrees to $19.5M Settlement Over Abilify Marketing". The Legal Intelligencer. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ↑ "ABILIFY Label, Section 2.3 pp. 7–8" (PDF). United States Food and Drug Administration. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-10-24. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ Staton, Tracy. "Pharma's Top 11 Marketing Settlements: Bristol-Myers Squibb - Abilify". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ↑ "Press Release: Lundbeck and Otsuka Pharmaceutical sign historic agreement to deliver innovative medicines targeting psychiatric disorders worldwide (OMX:LUN)". Lundbeck. November 11, 2011. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ↑ Megan Brooks (2014-01-30). "Top 100 Selling Drugs of 2013". Medscape. Archived from the original on 2015-10-31. Retrieved 2015-10-15.

- ↑ "BMS cuts salesforce on revised Abilify deal". PM Live. 7 November 2012. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ↑ Sagonowsky, Eric (December 1, 2016). "Lundbeck, Otsuka seek Abilify Maintena nod in bipolar disorder". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ↑ "Abilify Maintena 300mg & 400mg powder and solvent for prolonged-release suspension for injection and suspension for injection in pre filled syringe - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". UK Electronic Medicines Compendium. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ↑ "Barr Confirms Filing an Application with a Paragraph IV Certification for ABILIFY(R) Tablets" (Press release). Barr Pharmaceuticals, Inc. 2007-03-20. Archived from the original on 2018-09-16. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ↑ Susan Decker; Tom Randall (2010-11-15). "Bristol-Myers Partner Otsuka Wins Abilify Ruling - Bloomberg Business". Bloomberg L.P. Archived from the original on 2016-07-22. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ B1 EP application 0367141 B1, "Carbostyril derivatives", published 1996-10-01, assigned to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

- ↑ "Patent decision". UK Intellectual Property Office. 2006-09-19. Archived from the original on 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ↑ Michaelson, Jay (2014-11-09). "Mother's Little Anti-Psychotic Is Worth $6.9 Billion A Year". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 2017-03-18. Retrieved 2020-08-03.

- ↑ "FDA approves first generic Abilify to treat mental illnesses". Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ "Teva Launches Generic Abilify Tablets in the United States".}

- ↑ Citrome L (2015). "Aripiprazole Long-Acting Injectable Formulations for Schizophrenia: Aripiprazole Monohydrate and Aripiprazole Lauroxil". Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 9 (2): 169–86. doi:10.1586/17512433.2016.1121809. PMID 26573020.

- ↑ "Aristada (aripiprazole lauroxil) FDA Approval History". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2018.

- ↑ Staton, Tracy (December 14, 2016). "Bristol-Myers to pay $19.5 million in Abilify off-label marketing settlement". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the. "Press Announcements - FDA approves pill with sensor that digitally tracks if patients have ingested their medication". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-11-26. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ↑ Belluck, Pam (2017-11-13). "First Digital Pill Approved to Worries About Biomedical 'Big Brother'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2017-11-28. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ↑ Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (BNF) 79. Pharmaceutical Pr; 2020.

- ↑ "Australian Medicines Handbook 2013 [Internet]". Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DRUGDEX® System (Internet) [cited 2013 Jun 25]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- ↑ Kaplan J, Shah P, Faley B, Siegel ME (December 2015). "Case Reports of Aripiprazole Causing False-Positive Urine Amphetamine Drug Screens in Children". Pediatrics. 136 (6): e1625–8. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3333. PMID 26527556.

Further reading[edit | edit source]

- Dean L (2016). "Aripiprazole Therapy and CYP2D6 Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520375. Bookshelf ID: NBK385288.

External links[edit | edit source]

| External sites: | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers: |

|

- "Mechanism of Action of Aripiprazole". Psychopharmacology Institute.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)