| A guide to U.S. Politics |

| Hail to the Chief? |

| Persons of interest |

“”The electoral college is a disaster for a democracy.

|

| —Donald J. Trump, November 6, 2012.[note 1] (winner of the electoral college but not the popular vote in 2016)[1] |

The United States Electoral College consists of 538 people who are selected every 4 years to elect the President of the United States. Unlike most US colleges, it is known neither for academic excellence nor for athletic prowess. They would probably lose a football tournament against the Ivy League and a quiz against Notre Dame.

The 538 comes from the electors who represent the 100 US senators, the 435 US house members, and 3 for the District of Columbia (see the 23rd Amendment).

The basic design of the Electoral College was laid out in Article 2, Section 1 of the United States Constitution.[2] It explicitly gives the right to pick electors (and the right to make the rules for picking them) to the states. State legislatures today choose certain electors based on the statewide popular vote (with the exception of Maine and Nebraska), and those electors pledge to cast their votes based on the people that they are representing. In the past, these electors have been appointed through a number of different methods.[3]

Although electors nowadays pledge their vote to a specific candidate, it is possible for electors to cast their vote for a different candidate than what the state's voters sent them to vote for. These are called faithless electors, and the legality of being a faithless elector differs from state to state - see Wikipedia's article![]() for more. Faithless electors are uncommon and never come around in sufficient numbers to change the outcome of an election.

for more. Faithless electors are uncommon and never come around in sufficient numbers to change the outcome of an election.

How does it work?[edit]

How electors are chosen[edit]

“”Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress: but no Senator or Representative, or Person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector.

|

| —The US Constitution, Article 2, Section 1[2] |

Electors are ultimately chosen by state legislatures. There are very few restrictions on who can be chosen as an elector, though people currently in office cannot serve as electors[2]Sec 1 and people who have served in an insurrection/rebellion against the US also can't be chosen.[4] Aside from these limits, the states are basically free to choose how they want to choose electors. Nowadays, state legislatures choose electors based on the state's popular vote for president (except Maine and Nebraska), normally choosing electors from slates provided by the state's winning party (though the specifics on that vary by state[5]). Historically, there were a number of methods which states used to choose electors, but in the 1820s, using the state-wide popular vote emerged as the dominant way of choosing electors.[3]

What if no majority is reached?[edit]

The Constitution specifically states a candidate for President or Vice President must receive a majority of the electoral votes to win (currently 270 out of 538). If there is a 269-269 tie (or a third or fourth party siphons off enough electoral votes from the main parties), Congress would be in charge of electing the president. Should this happen, the House of Representatives would be responsible for electing the President and the Senate would be in charge of picking the Vice President, from the top three electoral college vote getters. However, not all Congresscritters and Senators can vote, since voting would be on a one state-one vote basis, hence the winner would need to get 26 votes. The constitution is silent on the possibility of a 25-25 tie or a 24-24-2 tie or any other non-majority outcome. That means that each state delegation would have to work this out on their own, and while a simple majority would be enough in a state that has a majority of one party or the other, it could present a problem in states that are evenly split — the Constitution is again silent on this issue.

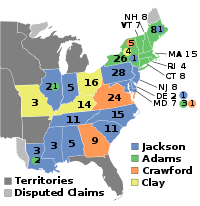

This has happened twice before in American history, in 1800 and in 1824 (luckily these have been the only two times). The 1824 election is particularly notable as it has been labeled the "corrupt![]() bargain." That year, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, and William Harris Crawford all ran. Jackson, Adams, and Crawford were the top three vote getters, Jackson had won a plurality of the electoral and popular votes and hoped that Congress would elect him; however, Adams won. Jackson supporters alleged that Clay instructed those states' votes which he controlled to vote for Adams, in exchange for Adams making him Secretary of State.

bargain." That year, Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, and William Harris Crawford all ran. Jackson, Adams, and Crawford were the top three vote getters, Jackson had won a plurality of the electoral and popular votes and hoped that Congress would elect him; however, Adams won. Jackson supporters alleged that Clay instructed those states' votes which he controlled to vote for Adams, in exchange for Adams making him Secretary of State.

Should no decision in Congress be reached on both the Presidential and Vice Presidential elections by inauguration day, the Speaker of the House would get sworn in.

What if the results are stupid and dumb?[edit]

If Congress hates the results of the electoral college and wants to reject them, they can get together at least one House member and at least one Senator who object to the votes. Once that happens, the House and Senate separately debate on the electoral votes being contested and separately hold a vote on whether or not to keep those electoral votes.[6] This has happened multiple times since 2000.[7]

But be careful about this, though, because the idea of congress objecting to electoral votes without a good reason to do so has led to people storming the capitol before.

History[edit]

Establishment[edit]

Of all the Founding Fathers, the one most closely linked to this method of election is James Madison. In the Federalist Papers No. 10 Madison spells out the dangers of factions and imparting too much power to a simple majority. In the Federalist Papers No. 39, he further developed the idea in that the federal executive should be elected in a manner that combines the state and federal system. He argued that the Constitution was designed to be a mixture of federal (state-based) and national (population-based) government. The Congress would have two houses, one federal and one national in character, while the President would be elected by a mixture of the two modes, giving some electoral power to the states and some to the people in general.

Moreover, it was argued that the system was set in place because a poor farmer in Georgia would not be able to know enough about presidential candidates from other states to vote for them. Therefore, local people vote for a local representative, who is then entrusted with the vote. The same idea could have been achieved by having Congress select the President, but this would have then made the President beholden to the Congress, violating the separation of powers between Congress and the Presidency.

Early elections[edit]

Electors were given two votes, both for President (unlike today where one vote is designated for President, one for Vice President) - the candidate with the highest vote total would be President, while the second highest would be Vice President. In the 1796 election, this played out with John Adams of the Federalist Party winning the most votes and Thomas Jefferson of the Democratic-Republican Party coming in second. The result was a President and Vice President who hated each other.

In 1800 Thomas Jefferson's party, the Democratic-Republicans, wanted Jefferson to get the most votes and Aaron Burr to get the second most. However, due to some irregularities during the election, Jefferson and Burr tied, throwing the election to the House of Representatives (which determines the winner in the case of a tie on a one state, one vote basis). Adams controlled the votes of enough states to prevent a majority. Thanks to some political wheeling and dealing (and the fact that Adams saw Jefferson as the lesser of two evils) the election went to Jefferson. At the time, this whole process was looked at very poorly as it involved some rather shady political dealings and a lot of drama.

In light of the 1800 election, the Electoral College had a major revision in 1804 with the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment, which was passed. This changed the electoral college so that electors had one vote for President and one vote for Vice President, making them separate elections.

Reconstruction Era[edit]

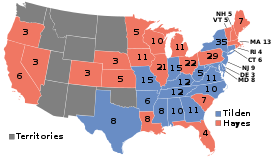

The 1876 Electoral College, where four states had disputed results and the Democrat lost by one electoral vote. The situation there got pretty rough

, to say the least.

, to say the least.

Recent times[edit]

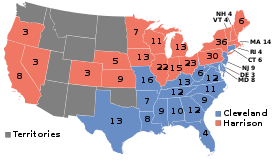

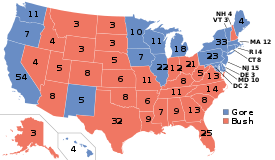

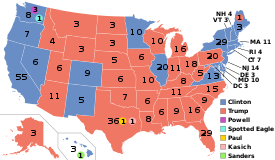

The 2016 Electoral College, another year where the electoral college picked a candidate who lost the popular vote. Also saw the greatest number of faithless electors from living candidates in US history.[9]

Defending the system[edit]

The big cities would control everything![edit]

If you entirely win over every single voter of the top 10 biggest cities (excluding the broader metropolitan area), you’ve only won 8% of the popular vote - far from enough to win an election. Even adding on a 100% win for every single one of the next 90 biggest cities, you’ve still only reached 19% of the whole population - again, nowhere close enough to win an election. This means that if a candidate appealed ONLY to the interests of big cities, they would lose in a landslide every time to a candidate with the popular vote.[11]

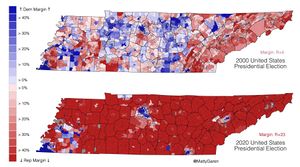

What's more, the Electoral College doesn't stop big cities within states from overpowering rural areas in those states. NYC's large population outweighs the New York upstate (delivering the state's electoral vote to democrats each year), Las Vegas in Nevada outweighs the rural parts of the rest of the state (which is largely desolate anyway), and Atlanta outweighs much of rural Georgia. However, the reverse holds true much of the time, too - in Tennessee, the cities are outweighed by the countryside, as is the case in Missouri, Kansas, and Indiana. In a country with a stark urban-rural divide, this is usually how elections end up - the dominating party (either the urban party or the rural party) is the one that outweighs the other. The most dominating party on the political scene wins the election, shocking! When Electoral College defenders say that the cities would control everything, they ignore that the rural areas will also sometimes dominate in elections (and that if A dominating over B is a problem, the reverse just might happen to also be a problem!). However, the Electoral College stops neither the urban nor the rural from controlling everything - presidential elections still remain winner-take-all so that if an urban area even slightly outweighs a rural area, the urban area's party will get all of that state's electoral votes.

It's also worth noting that the Founding Fathers didn't have this problem in mind at all when they designed the Electoral College, especially considering that 95% of America's population was in rural areas at the time![]() (as opposed to 20% of the US population today). The extent to which cities have grown probably would have been unimaginable to the Founding Fathers at that time, not to mention that the urban-rural divide we see in politics today probably wasn't something they had on their minds... considering that such a divide didn't exist back then. The Founding Fathers did however have more concern with big states overpowering smaller states (see below), which played into a lot of their debate about federalism and centralized government.

(as opposed to 20% of the US population today). The extent to which cities have grown probably would have been unimaginable to the Founding Fathers at that time, not to mention that the urban-rural divide we see in politics today probably wasn't something they had on their minds... considering that such a divide didn't exist back then. The Founding Fathers did however have more concern with big states overpowering smaller states (see below), which played into a lot of their debate about federalism and centralized government.

The big states would control everything![edit]

This is basically just a revision of the last point to focus on big states rather than big cities.

- Smaller states are already ignored with the EC, with the focus instead being on swing states.[12] This isn’t surprising, either - in a system where some states are safely in the hands of a campaign while other states are up for grabs, campaigns gain more electoral votes by focusing on states which are easier to grab for themselves rather than trying to snatch a safe state from the hands of the opposing campaign. This bears out in the data, too - in 2004, the last 5 weeks of campaigning was spent in a select few swing states.[13] Similar results came out of 2008, 2012,[14] 2016,[15] (some analysis of the 2016 data here[16]), and 2020.[17]

- This is essentially advocating for affirmative action for smaller states, which should be especially concerning to people who usually put out anti-affirmative action arguments: conservatives.

- If you don’t want some people in California deciding life for Wyomingans that’s fine, that’s a reasonable position to have - but the EC doesn’t really fix this so much as it pushes the situation closer to being flipped - Wyoming’s chosen candidate deciding life for Californians. A better way to stop this cross-regional influence would be to localize most power, so that the local governments and state government of Wyoming has more say over its own policy than the federal government does.

People who argue this also tend to conveniently ignore that under the Electoral College, you still only need to win 11 or 12 of the most populous states to win an election.

Democracy is bad[edit]

Some people will say that "pure democracy" (in this case, everyone's vote for president weighing the same) always leads to failure and collapse. Nevermind that the overwhelming majority of countries in the world elect their head of state via a system which directly uses the national popular vote,[18] rather than via an electoral college or equivalent.

- The EC is still based on a democratic vote, the only real difference being that the EC skews the democratic vote based on what state you live in. By this point, it’s more likely that you have a problem with democratic voting than you do with specific implementations of it.

- There are literally thousands of examples of democracy being successful within the US, primarily in the form of mayors, governors, and so on. If you extend that back historically, you’ll get hundreds of thousands of examples to choose from - and that’s just within the US. These local or state governments haven’t collapsed or been hindered by a popular vote being used there, as far as we can tell.

- A bare majority still usually has an advantage in EC - usually the person with the most votes also wins the EC. If your intention is to prevent the mob of the majority from tyrannizing the minority, the EC is a horrible solution.

Two wolves and a lamb/majority tyranny[edit]

This is sort of a variation of the "democracy is bad" argument, except focusing on a specific anti-democracy argument. Put simply, they argue that a majority of the population can use democracy to gain power and oppress minority groups, smaller political movements, and so on. This is either argued in the context of the Electoral College thwarting the pro-slavery Democrats (1876 and 1888 elections) or in the context of non-plurality winners in general (2000 and 2016).

When it comes to minority suppression (1876 and 1888):

- The Electoral College wasn’t implemented with the foresight of knowing where minorities would be located nowadays; its method of designating power does not keep racial, ethnic, class, etc. minorities in mind whatsoever. It’s simply blind to those aspects of the population’s makeup. Even if it was originally designed to protect a certain minority group, there’s no good reason for the designers to assume that it would still protect that certain minority group today. They can’t just predict the demographic makeup and geographic distribution of the American population 350 years into the future.

- The Electoral College also doesn’t have any mechanism built into it which is able to specifically target candidates with bad or oppressive policies - all it really does is weigh your vote differently based on what state you live in. If a majority of electoral votes are cast in favor of someone with really bad and oppressive policies, that’s that.

- It's hard to even say that the Founding Fathers had this in mind in the first place, given that many of them didn't care for the rights of black people and even went so far as to exploit them for political power. Why would they design a system which benefits those exact people?

- Let's not also forget that southern democrats aggressively defended the Electoral College in the 60s and 70s as they viewed it as a tool to advance their own segregationist agenda.[19]

When it comes to political suppression (2000 and 2016):

- Knowing how the EC can allow the candidate with the most votes to lose, this metaphor applied to the EC could very well be ‘one wolf and two lambs deciding what to eat for dinner’ with the wolf, not the lambs, having the final say. The minority - in this case, the wolf - would have more of a say than the lambs. Even if you fully accept that there’s a problem with tyranny of the majority, you still have to admit that the electoral college sometimes replaces tyranny by majority with tyranny by minority (and that ‘sometimes’ is getting more likely to happen given because close elections have been more common as of late[20]). As it turns out, the criticisms made of “tyranny of the majority” can usually be more strongly pushed against “tyranny of the minority”.

It's a republic, not a democracy[edit]

This is largely just a semantical difference and it doesn't offer much substance to the discussion. Usually people who argue this think that democracies lead to mob rule or that it would lead to everyone having to vote on every single policy individually. Good thing the national popular vote system doesn't advocate for either of those!

Swing states change[edit]

The fact that swing states change shouldn't be used to dismiss the broader populace in favor of those who happen to live in swing states in a particular year. That's pretty simple and easy to understand.

Voter fraud is mitigated[edit]

Under the EC, it usually takes fewer votes to flip a few strategic states than it takes to flip the popular vote - the outcome of a state election hinging on 10,000 votes is around 4% vs 0.1% in a national popular election[21] - and keep in mind that 4% applies to each state individually, rather than the national election as a whole. In this way, the EC makes voter fraud more dangerous than the NPV.

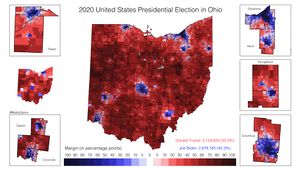

In recent times, the margins needed to flip individual states (and thus the election) have been pretty close. Every single time, it comes in contrast with the much larger margin that would be needed to flip the national popular vote.

- In 2000, it would have taken 537 votes in Florida to flip the whole election’s result, as opposed to several hundred thousand votes which would have been needed to flip the national popular vote.

- In 2004, you would have had to flip a little more than 50,000 votes in the single state of Ohio to change the result of the entire 2004 election in favor of John Kerry, who lost the popular vote by over 3 million votes. Note that in this particular instance, the EC would have benefitted a Democrat, not a Republican.

- In 2016, it would have taken less than 100,000 votes distributed across PA, WI, and MI to change the election outcome, rather than nearly 3 million votes to change the popular vote count.

- In 2020, despite Joe Biden's massive 7 million vote lead, it would have only taken only around 40,000 votes in Georgia, Arizona, and Wisconsin to tie the results of the Electoral College, which would almost certainly have resulted in a Trump victory given the way that ties are resolved in the EC.[note 2]

This also assumes that voter fraud is a big issue in the first place, which it isn’t really at this point.[22] There are other election problems which are worth keeping in mind though, such as flawed voter rolls, the difficulty which can come about for detecting fraud, and so on.

By using this argument, you also kind of accidentally admit that your vote only really matters if it’s cast in a swing state. Your argument would assume that fraud doesn't matter if it's cast in a safe state but that it would matter in a swing state.

The Founding Fathers[edit]

A lot of people appeal to the Founding Fathers as the ultimate guide for our country simply because the founding fathers proposed it, despite the fact that the Founding Fathers disagreed on a lot amongst themselves (not to mention there's even nuance on the specific beliefs which each Founding Father had) and despite the fact that most of their beliefs would not map out onto the contemporary political landscape.[23] Many of the Founding Fathers would scoff at the rights and opportunities which women and black people have today in America, but that doesn't make them automatically right and modern society automatically wrong. Sure, the founding fathers set up a decent system to start with, but their word is by no means the final say on the subject (again, it wasn't and still isn't a static system).

Again, keep in mind that treating the founding fathers as some sort of monolith in their beliefs is dumb, especially considering that there’s nuance even to the beliefs of individual founders. This is true for issues like slavery for instance, where many of them (not all) owned slaves and took few meaningful steps to end the practice, yet most of these people (not all) still opposed the practice. You can’t just take this info as an indication that the founding fathers as a whole liked or disliked slavery - there’s too much nuance for that. For stuff regarding the founding fathers as a whole group, there’s way more nuance than people like to admit, especially when they want to use it for a talking point about how “this important group supported [thing I like].”

The EC, as well as America’s voting system in general, has not been a static system - even when the Founding Fathers were still alive and still had considerable influence (this means that the Founding Fathers themselves recognized that the original system wasn’t perfect and that changes would sometimes be needed!). To name a few examples of changes that happened:

- For over half a century in the US, many states simply did not hold a vote for the general populace and instead just had their electors cast electoral votes. In the 1788-9 presidential election only Pennsylvania and Maryland had a vote,[24] most states didn’t have a vote until 1824,[25] and a couple states like South Carolina went on without a vote for even longer.[26] Modern proponents of the EC don’t advocate for getting rid of statewide-votes, even though the country started out with very few state-wide votes.

- In 1870, the original Three-Fifths Compromise was abandoned in favor of granting black people full suffrage via the 15th Amendment. Modern proponents of the EC don’t advocate for going back to the original system in this regard, even though it was a system reached by the founding fathers themselves.

- After the 1800 election (just 4 elections into the country’s history), the 12th Amendment was passed which directly altered the way that electors were able to cast their votes. This forced electors to cast one vote for president and one for vice president, rather than be able to cast both votes for just president or just vice president. More context about the 12th amendment is provided here.[27]

"Wrong winner" results aren't common[edit]

This doesn't justify keeping the system which lets these results happen. If anything, saying that "it's good this doesn't happen often" is an acknowledgement that these wrong winner results are a bad thing in the first place.

The process by which a president is chosen is very important, and even one election in which the popular vote and EC diverge will still matter a lot for the country’s future. For example, Donald Trump’s court appointees will likely reshape federal courts for decades,[28] despite him only being a one-term president. You could also argue that wrong winner elections aren’t as rare as you might think and will likely be more common as elections since the 1980s have been pretty close races.[20]

The electoral college has a rate of electing popular vote losers around 5-10% of the time. If a sport was given a rule that 5-10% of the time, the loser would win, people would think that's dumb, and the office of the Presidency is far more important than the typical sports game is.

It balances the field for Republicans[edit]

This argument of "balancing it out for the Republicans" is extremely dumb when you look back at history. There have been a number of times in the past where we see one party dominate; Republicans dominated during and after Reconstruction, Democrats dominated during the Great Depression, and Democratic-Republicans dominated during the country's early years. These all took place while the EC was being used, too. Was it wrong for the electoral college to let these groups dominate for long periods of time? If not, what's the problem with letting a certain party dominate under a popular vote system?

Also, Republicans could definitely win the popular vote more often if they campaigned with it in mind. Right now, both parties orient their campaigns around winning certain swing states, not around winning the popular vote - and that's because of how the electoral system currently works. If we use the results of swing state approaches to make conclusions about a popular vote approach, we'll be misled because we're comparing apples to oranges.

On top of all of this, the "balance it out for Republicans" argument is fundamentally flawed because it assumes the electoral college consistently benefits Republicans in the way people thinks it does, which probably isn't true. The benefit provided by the EC jumps from party to party each year and isn't really predictable - it just so happens that this advantage brought Republicans just over the edge twice since 2000.[29]

Rejecting the system[edit]

Keep in mind that the following critiques are of the current Electoral College system, how states currently allocate votes, and how that impacts elections right now. A decent national popular vote system can still be implemented within the Electoral College framework, by having all electoral votes go to the popular vote winner or by having electoral votes cast proportionally relative to the popular vote within each state.

Arbitrariness[edit]

The Electoral College has the effect of making the intricacies of state borders matter an awful lot. For example, moving Escambia county (home of the city of Pensacola) from Florida to Alabama would have netted the whole state for Al Gore in 2000 - and the whole election along with it. Similarly, it would have only taken the moving of 3 counties to net Hillary Clinton the 2016 election.[30] In both of these cases, we see counties moved within their own regions to states which are otherwise similar in culture, industry, and so on - meaning that the changes in the electoral count can't be attributed to regional differences but rather to lines which are basically arbitrary. This sort of stuff is especially troubling for close elections, where small border changes can make it or break it for certain candidates in a state. Tools exist that allow people (including you!) to experiment with changes to state borders and how they would have impacted the results of Presidential Elections. The fact that minor changes can have such a big impact on election results shows just how shaky the results of each election are, and how different they could have ended up being. Justifications of the results of a system that produces results this fragile and arbitrary tend to be post-hoc justifications, especially considering that nobody really asked for state lines to have that arbitrary an impact on the election results.

Here are some examples where this arbitrariness can let you move just a few counties and flip the outcome of an election, regardless of who the nationwide popular vote favored. Again, feel free to use this to check for yourself and try out other pathways.

- in 2000, moving Escambia county from FL to AL would have changed the election to favor Al Gore.

- in 2004, moving Monroe and Washtenaw from MI to OH and moving Beaver and Alleghany from PA to OH would have changed the election in favor of John Kerry.

- in 2016, moving Lake from IL to WI, Lucas from OH to MI, and Camden from NJ to PA would have changed the election to favor Hillary Clinton.

- in 2020, moving Philadelphia from PA to NJ, Apache from AZ to NM, and Chatham from GA to SC would have changed the election to favor Donald Trump.

When moving just a few counties to other states within their region will flip-flop the results of an entire election, it's clear that the system we're dealing with is pretty fragile and that we've had a lot of near-misses just in the recent past alone. It shows that under the Electoral College, what matters is not the larger box which is the United States as a whole, but rather the smaller boxes which are the states themselves, and where a box's boundaries are drawn can change things for basically everyone without any good reason.

People want it gone[edit]

Over the past several decades, a decisive majority of Americans have consistently said they would approve of a national popular vote system over the Electoral College.[31] This consensus held firm even after the 2000 election, too. There was close to bipartisan consensus on this in the Obama years, with majorities of Republicans and Democrats in agreement on this.[32] However, a majority of Republicans switched to supporting the Electoral College after the 2016 election.[33][34] We've yet to figure out why that happened!

This historical bipartisanship against the Electoral College actually culminated in the 60s and 70s in a proposed Constitutional Amendment to abolish it, something which Richard Nixon (a Republican) supported. The measure passed the House 338-70, but was killed in the Senate via filibuster - and the main opposition to the Amendment actually came from southern segregationists like Strom Thurmond who believed that a national popular vote system would compromise the South's ability to push segregationist policy on the national stage.[19]

Compromises election integrity[edit]

Because having 51 elections (50 states + DC) rather than one nationwide election increases the chance of a disputed election occurring,[21] this means that disputed elections are more common and this in turn leads to more legal challenges, public anxiety, and public distrust of the election results. On top of this, close elections are more likely to see the outcome influenced by fraud - 0.1% of the vote count being fraudulent matters a lot more when an election is decided by a 0.2pt margin than by a 20pt margin. With swing states getting most of the focus in elections and having the most decisive say, their close results can be easily stained by allegations of fraud. This was effectively weaponized in 2020 by publicizing fraud allegations in swing states, to the point at which half of Republicans believed that Biden won due to fraud.[35]

Only swing states matter[edit]

.png)

“”It doesn’t matter whether Clinton wins New York [which is worth 29 electoral votes] by a 30 percent margin or a 10 percent margin, since she’ll get the same amount of electoral votes either way. But the difference between winning Florida by 0.1 percent and losing it by 0.1 percent is crucial, since 29 electoral votes could flip.

|

| —guy at Vox who wrote a decent op-ed[36] |

When certain states will reap more reward for what you sow in them, it makes more sense to focus a campaign in those certain states - that is, states that can be won with less effort. When comparing a state like Wyoming (3 electoral votes, safely votes Republican every cycle) with a state like Florida (29 electoral votes, could swing to either party), it's clear that a win for either party in closely divided Florida would give them more of a reward than a win in safely Republican Wyoming. Apply this onto a broader electoral map and you end up with campaigns which focus almost exclusively on swing states, with most of the population being completely ignored.

The correlation between expected swing states and voter turnout is rather strong, suggesting that voters who are not in swing states are still discouraged from voting as they feel that their vote counts less.[37] This depression can be explained by other things which are also related to the electoral college, e.g. where campaigns choose to focus on getting the vote out. This means that whether or not you're in a swing state can have quite an impact on if you even decide to go out and vote in the first place.

Small states overrepresented[edit]

Another problem is the severe imbalance between the less populated states and the densely populated states. Because 2 Electors are added for each state to represent the senators of that state, and because there are 2 senators per state regardless of the state (whereas the number of house members a state gets is determined by its population), those extra two senators can dramatically shift the voting power of a state. With smaller states (like Wyoming, Vermont, and so on) the 2 Senators can double or triple the voting power of those states, while states like California and Texas get a much smaller relative bump in voting power. This results in stuff like the vote of a Wyoming voter being valued 3.8 times more than that of a California voter.[38]

Small state bias could easily be overrated, though, as its power is only enough to flip the electoral vote in extremely close elections (like 2000, for example - where the electoral vote was 271-266).[39]

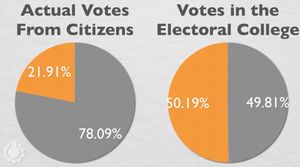

"Wrong winners" results[edit]

One of the most common critiques by far is that the system can produce an election winner who didn't win the popular vote. These results are basically the result of multiple above criticisms - the arbitrary impact of state borders, the possible overrepresentation of small states, the wildly disproportionate focus on swing states, and so on. It undermines the idea that each person has one vote (as small state or swing state votes are functionally more important than other votes under the Electoral College), and essentially decides that people don't have the say in the election which they think that they do.

Does it have to be this way?[edit]

Only Nebraska and Maine have legal provisions allowing for the electors to be determined by something other than statewide winner takes all (which happened in Nebraska in 2008, when Barack Obama actually won one of the state's electoral votes by winning one of the Congressional districts), (and in Maine in 2016 when Donald Trump actually won one of the state's electoral votes by winning one of the Congressional districts). Other states could also follow this model, which could make the Electoral College somewhat more democratic, especially in swing states, but it's difficult to conceive of a world in which state politicians would willingly give the opposing party an advantage in the national election. And the model as adopted by Nebraska and Maine is not exactly the be all end all either, as the allocation is not by statewide popular vote, but based on pluralities in Congressional Districts. Those in turn are not perfect indicators of the actual will of the people either.

A more realistic possibility is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact![]() , which cleverly games the system such that the "safe states" gang up on the swing states and give 100% of their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote, making the electoral college obsolete without actually getting rid of it. So far, it's been signed by about half of the states required for it take effect. Unfortunately, red states have thus far not signed on in any appreciable number, nor have (for obvious reasons) swing states.

, which cleverly games the system such that the "safe states" gang up on the swing states and give 100% of their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote, making the electoral college obsolete without actually getting rid of it. So far, it's been signed by about half of the states required for it take effect. Unfortunately, red states have thus far not signed on in any appreciable number, nor have (for obvious reasons) swing states.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- https://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/the-electoral-college.aspx for people who still don't understand the process

- https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/answering-myths National Popular Vote's page responding to common claims about the Electoral College

- "Let The People Pick the President", book by Jesse Wegman

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Twitter: @realDonaldTrump, 8:45 PM ===6 Nov 2012

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/article-2/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 https://www.fairvote.org/how-the-electoral-college-became-winner-take-all

- ↑ https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-14/ section 3

- ↑ https://electoralvotemap.com/how-are-electors-chosen/

- ↑ "How Can the Results of a Presidential Election Be Contested? pdf

- ↑ "Democrats Have Been Shameless About Your Presidential Vote Too" NYTimes Op-ed

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on 1824 United States presidential election.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Faithless electors in the 2016 United States presidential election.

- ↑ The growing Democratic domination of nation’s largest counties from Pew Research

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 CGP Grey's video The Trouble with the Electoral College

- ↑ https://www.fairvote.org/yet-again-just-three-states-draw-the-majority-of-campaign-attention-presidential-tracker-update-october-17-201

- ↑ http://archive.fairvote.org/media/research/who_picks_president.pdf

- ↑ https://www.fairvote.org/fairvote-maps-the-2012-presidential-campaign

- ↑ https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/14Lxw0vc4YBUwQ8cZouyewZvOGg6PyzS2mArWNe3iJcY/edit#gid=0

- ↑ https://theweek.com/articles/840362/electoral-college-doesnt-benefit-small-states-what-does-even-dumber

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/10/17/us/politics/trump-biden-campaign-ad-spending.html

- ↑ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/File:Electoral_systems_for_heads_of_state_map.svg

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 [https://www.history.com/news/electoral-college-nearly-abolished-thurmond How the Electoral College Was Nearly Abolished in 1970 ] from History.com

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/section_9.3

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Bloomberg article about it and the study itself

- ↑ Brennan Center's compilation of resources about that

- ↑ The Founding Fathers Fallacy

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/File:PresidentialCounty1788Colorbrewer.gif

- ↑ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/File:PresidentialCounty1824Colorbrewer.png

- ↑ https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/File:PresidentialCounty1848Colorbrewer.gif

- ↑ https://uselectionatlas.org/INFORMATION/INFORMATION/electcollege_history.php

- ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/mar/10/trump-legacy-conservative-judges-district-courts

- ↑ https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/will-the-electoral-college-doom-the-democrats-again/

- ↑ https://khayeswilson.medium.com/the-best-maps-from-redraw-the-states-538861cc44ed

- ↑ https://news.gallup.com/poll/2323/Americans-Historically-Favored-Changing-Way-Presidents-Elected.aspx

- ↑ https://www.nationalpopularvote.com/polls

- ↑ https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/03/13/a-majority-of-americans-continue-to-favor-replacing-electoral-college-with-a-nationwide-popular-vote/

- ↑ https://news.gallup.com/poll/198917/americans-support-electoral-college-rises-sharply.aspx

- ↑ https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-poll-idUSKBN27Y1AJ

- ↑ https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2016/11/7/12315574/electoral-college-explained-presidential-elections-2016

- ↑ https://www.npr.org/2016/11/26/503170280/charts-is-the-electoral-college-dragging-down-voter-turnout-in-your-state

- ↑ http://www.bartcop.com/elec-unfair.htm

- ↑ https://nytimes.com/2019/03/22/upshot/electoral-college-votes-states.html