| Atopic dermatitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Atopic eczema, infantile eczema, prurigo Besnier, allergic eczema, neurodermatitis[1] |

| |

| Atopic dermatitis of the inside crease of the elbow | |

| Specialty | Dermatology, Clinical Immunology and Allergy |

| Symptoms | Itchy, red, swollen, cracked skin[2] |

| Complications | Skin infections, hay fever, asthma[2] |

| Usual onset | Childhood[2][3] |

| Causes | Unknown[2][3] |

| Risk factors | Family history, living in a city, dry climate[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after ruling out other possible causes[2][3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Contact dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis[3] |

| Treatment | Avoiding things that worsen the condition, daily bathing followed by moisturising cream, steroid creams for flares[3] Humidifier |

| Frequency | ~20% at some time[2][4] |

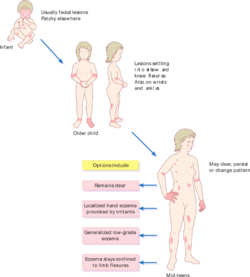

Atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as atopic eczema, is a long-term type of inflammation of the skin (dermatitis).[2] It results in itchy, red, swollen, and cracked skin.[2] Clear fluid may come from the affected areas, which often thickens over time.[2] While the condition may occur at any age, it typically starts in childhood, with changing severity over the years.[2][3] In children under one year of age, much of the body may be affected.[3] As children get older, the areas on the insides of the knees and elbows are most commonly affected.[3] In adults, the hands and feet are most commonly affected.[3] Scratching the affected areas worsens the symptoms, and those affected have an increased risk of skin infections.[2] Many people with atopic dermatitis develop hay fever or asthma.[2]

The cause is unknown but believed to involve genetics, immune system dysfunction, environmental exposures, and difficulties with the permeability of the skin.[2][3] If one identical twin is affected, the other has an 85% chance of having the condition.[5] Those who live in cities and dry climates are more commonly affected.[2] Exposure to certain chemicals or frequent hand washing makes symptoms worse.[2] While emotional stress may make the symptoms worse, it is not a cause.[2] The disorder is not contagious.[2] A diagnosis is typically based on the signs and symptoms.[3] Other diseases that must be excluded before making a diagnosis include contact dermatitis, psoriasis, and seborrheic dermatitis.[3]

Treatment involves avoiding things that make the condition worse, daily bathing with application of a moisturising cream afterwards, applying steroid creams when flares occur, and medications to help with itchiness.[3] Things that commonly make it worse include wool clothing, soaps, perfumes, chlorine, dust, and cigarette smoke.[2] Phototherapy may be useful in some people.[2] Steroid pills or creams based on calcineurin inhibitors may occasionally be used if other measures are not effective.[2][6] Antibiotics (either by mouth or topically) may be needed if a bacterial infection develops.[3] Dietary changes are only needed if food allergies are suspected.[2]

Atopic dermatitis affects about 20% of people at some point in their lives.[2][4] It is more common in younger children.[3] Females are slightly more affected than males.[7] Many people outgrow the condition.[3] Atopic dermatitis is sometimes called eczema, a term that also refers to a larger group of skin conditions.[2] Other names include "infantile eczema", "flexural eczema", "prurigo Besnier", "allergic eczema", and "neurodermatitis".[1]

Signs and symptoms

People with AD often have dry and scaly skin that spans the entire body, except perhaps the diaper area, and intensely itchy red, splotchy, raised lesions to form in the bends of the arms or legs, face, and neck.[8][9][10][11][12]

AD commonly affects the eyelids, where signs such as Dennie-Morgan infraorbital fold, infra-auricular fissure, and periorbital pigmentation can be seen.[13] Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation on the neck gives the classic "dirty neck" appearance. Lichenification, excoriation, and erosion or crusting on the trunk may indicate secondary infection. Flexural distribution with ill-defined edges with or without hyperlinearity on the wrist, finger knuckles, ankle, feet, and hands are also commonly seen.[14]

Causes

The cause of AD is not known, although some evidence indicates genetic, environmental, and immunologic factors.[15]

Climate

Low humidity, and low temperature increase the prevalence and risk of flares in patients with atopic dermatitis.[16]

Genetics

Many people with AD have a family history or a personal history of atopy. Atopy is an immediate-onset allergic reaction (type-1 hypersensitivity reaction mediated by IgE) that may manifest as asthma, food allergies, AD, or hay fever.[8][9] Up to 80% of people with atopic dermatitis have elevated total or allergen-specific IgE levels.[17]

About 30% of people with atopic dermatitis have mutations in the gene for the production of filaggrin (FLG), which increase the risk for early onset of atopic dermatitis and developing asthma.[18][19]

Hygiene hypothesis

According to the hygiene hypothesis, early childhood exposure to certain microorganisms (such as gut flora and helminth parasites) protects against allergic diseases by contributing to the development of the immune system.[20] This exposure is limited in a modern "sanitary" environment, and the incorrectly developed immune system is prone to develop allergies to harmless substances.

Some support exists for this hypothesis with respect to AD.[21] Those exposed to dogs while growing up have a lower risk of atopic dermatitis.[22] Also, epidemiological studies support a protective role for helminths against AD.[23] Likewise, children with poor hygiene are at a lower risk for developing AD, as are children who drink unpasteurized milk.[23]

Allergens

In a small percentage of cases, atopic dermatitis is caused by sensitization to foods.[24] Also, exposure to allergens, either from food or the environment, can exacerbate existing atopic dermatitis.[25] Exposure to dust mites, for example, is believed to contribute to one's risk of developing AD.[26] A diet high in fruits seems to have a protective effect against AD, whereas the opposite seems true for fast foods.[23] Atopic dermatitis sometimes appears associated with celiac disease and nonceliac gluten sensitivity, and the improvement with a gluten-free diet (GFD) indicates that gluten is a causative agent in these cases.[27][28]

Role of Staphylococcus aureus

Colonization of the skin by the bacterium S. aureus is extremely prevalent in those with atopic dermatitis.[29] Abnormalities in the skin barrier of persons with AD are exploited by S. aureus to trigger cytokine expression, thus aggravating the condition.[30]

Hard water

Atopic dermatitis in children may be linked to the level of calcium carbonate or "hardness" of household water, when used to drink.[31] So far, these findings have been supported in children from the United Kingdom, Spain, and Japan.[31]

Pathophysiology

Excessive type 2 inflammation underlies the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis.[32][33]

Disruption of the epidermal barrier is thought to play an integral role in the pathogenesis of AD.[17] Disruptions of the epidermal barrier allows allergens to penetrate the epidermis to deeper layers of the skin. This leads to activation of epidermal inflammatory dendritic and innate lymphoid cells which subsequently attracts Th2 CD4+ helper T cells to the skin.[17] This dysregulated Th2 inflammatory response is thought to lead to the eczematous lesions.[17] The Th2 helper T cells become activated, leading to the release of inflammatory cytokines including IL-4, IL-13 and IL-31 which activate downstream Janus kinase (Jak) pathways. The active Jak pathways lead to inflammation and downstream activation of plasma cells and B lymphocytes which release antigen specific IgE contributing to further inflammation.[17] Other CD4+ helper T-cell pathways thought to be involved in atopic dermatitis inflammation include the Th1, Th17, and Th22 pathways.[17] Some specific CD4+ helper T-cell inflammatory pathways are more commonly activated in specific ethnic groups with AD (for example, the Th-2 and Th-17 pathways are commonly activated in Asian people) possibly explaining the differences in phenotypic presentation of atopic dermatitis in specific populations.[17]

Mutations in the filaggrin gene, FLG, also cause impairment in the skin barrier that contributes to the pathogenesis of AD.[17] Filaggrin is produced by epidermal skin cells (keratinocytes) in the horny layer of the epidermis. Filaggrin stimulates skin cells to release moisturizing factors and lipid matrix material, which cause adhesion of adjacent keratinocytes and contributes to the skin barrier.[17] A loss-of-function mutation of filaggrin causes loss of this lipid matrix and external moisturizing factors, subsequently leading to disruption of the skin barrier. The disrupted skin barrier leads to transdermal water loss (leading to the xerosis or dry skin commonly seen in AD) and antigen and allergen penetration of the epidermal layer.[17] Filaggrin mutations are also associated with a decrease in natural antimicrobial peptides found on the skin; subsequently leading to disruption of skin flora and bacterial overgrowth (commonly Staphylococcus aureus overgrowth or colonization).[17]

Atopic dermatitis is also associated with the release of pruritogens (molecules that stimulate pruritus or itching) in the skin.[17] Keratinocytes, mast cells, eosinophils and T-cells release pruritogens in the skin; leading to activation of Aδ fibers and Group C nerve fibers in the epidermis and dermis contributing to sensations of pruritus and pain.[17] The pruritogens include the Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-13, IL-31, histamine, and various neuropeptides.[17] Mechanical stimulation from scratching lesions can also lead to the release of pruritogens contributing to the itch scratch cycle whereby there is increased pruritus or itch after scratching a lesion.[17] Chronic scratching of lesions can cause thickening or lichenification of the skin or prurigo nodularis (generalized nodules that are severely itchy).[17]

Diagnosis

AD is typically diagnosed clinically, meaning it is based on signs and symptoms alone, without special testing.[34] Several different criteria developed for research have also been validated to aid in diagnosis.[35] Of these, the UK Diagnostic Criteria, based on the work of Hanifin and Rajka, has been the most widely validated.[35][36]

| People must have itchy skin, or evidence of rubbing or scratching, plus three or more of: |

|---|

| Skin creases are involved - flexural dermatitis of fronts of ankles, antecubital fossae, popliteal fossae, skin around eyes, or neck, (or cheeks for children under 10) |

| History of asthma or allergic rhinitis (or family history of these conditions if patient is a child ≤4 years old) |

| Symptoms began before age 2 (can only be applied to patients ≥4 years old) |

| History of dry skin (within the past year) |

| Dermatitis is visible on flexural surfaces (patients ≥age 4) or on the cheeks, forehead, and extensor surfaces (patients<age 4) |

Treatments

No cure for AD is known, although treatments may reduce the severity and frequency of flares.[8]

Humidity

A humidifier can be used to prevent low indoor humidity during winter (especially with indoor heating), and dry season. And a dehumidifier can be used during seasons with excessive humidity.

Applying moisturisers may prevent the skin from drying out and decrease the need for other medications.[37] Affected persons often report that improvement of skin hydration parallels with improvement in AD symptoms.[8]

Lifestyle

Health professionals often recommend that persons with AD bathe regularly in lukewarm baths, especially in salt water, to moisten their skin.[9][38] Avoiding woolen clothing is usually good for those with AD. Likewise silk, silver-coated clothing may help.[38] Dilute bleach baths have also been reported effective at managing AD.[38]

Diet

The role of vitamin D on atopic dermatitis is not clear, but some evidence shows that vitamin D supplementation may improve its symptoms.[39][40]

Studies have investigated the role of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (LCPUFA) supplementation and LCPUFA status in the prevention and treatment of AD, but the results are controversial. Whether the nutritional intake of n-3 fatty acids has a clear preventive or therapeutic role, or if n-6 fatty acids consumption promotes atopic diseases is unclear.[41]

Several probiotics seem to have a positive effect, with a roughly 20% reduction in the rate of AD.[42][43] The best evidence is for multiple strains of bacteria.[44]

In people with celiac disease or nonceliac gluten sensitivity, a gluten-free diet improves their symptoms and prevents the occurrence of new outbreaks.[27][28]

Medication

Topical corticosteroids, such as hydrocortisone, have proven effective in managing AD.[8][9] If topical corticosteroids and moisturisers fail, short-term treatment with topical calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus or pimecrolimus may be tried, although their use is controversial, as some studies indicate that they increase the risk of developing skin cancer or lymphoma.[8][45] A 2007 meta-analysis showed that topical pimecrolimus is not as effective as corticosteroids and tacrolimus.[46] A 2015 meta-analysis, though, indicated that topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus are more effective than low-dose topical corticosteroids, and found no evidence for increased risk of malignancy or skin atrophy.[47] In 2016, crisaborole, an inhibitor of PDE-4, was approved as a topical treatment for mild-to-moderate eczema.[48][49]

Other medications used for AD include systemic immunosuppressants such as ciclosporin, methotrexate, interferon gamma-1b, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine.[8][50] Antidepressants and naltrexone may be used to control pruritus (itchiness).[51] Leukotriene inhibitors such as monteleukast are of unclear benefit as of 2018.[52]

In 2017, the monoclonal antibody(mAb) dupilumab under the trade name Dupixent was approved to treat moderate-to-severe eczema.[53] In 2021, an additional monoclonal antibody, tralokinumab, was approved in the EU & UK with the trade name Adtralza then later in the US as Adbry for similarly severe cases.[54][55] Another monoclonal antibody treatment, lebrikizumab, is in phase 3 trials in the US; the drug has been granted Fast Track Designation by the FDA, and Eli Lilly and Company is expected to apply for FDA approval of the drug in the second half of 2022.[56]

Some JAK inhibitors such as abrocitinib, trade name Cibinquo,[57] and upadacitinib, trade name Rinvoq,[58] have been approved in the US for the treatment of moderate-to-severe eczema as of January 2022.

Tentative, low-quality evidence indicates that allergy immunotherapy is effective in AD.[59] This treatment consists of a series of injections or drops under the tongue of a solution containing the allergen.[59]

Antibiotics, either by mouth or applied topically, are commonly used to target overgrowth of S. aureus in the skin of people with AD, but a 2019 meta-analysis found no clear evidence of benefit.[60]

Light

A more novel form of treatment involves exposure to broad- or narrow-band ultraviolet (UV) light. UV radiation exposure has been found to have a localized immunomodulatory effect on affected tissues and may be used to decrease the severity and frequency of flares.[61][62] In particular, the usage of UVA1 is more effective in treating acute flares, whereas narrow-band UVB is more effective in long-term management scenarios.[63] However, UV radiation has also been implicated in various types of skin cancer, and thus UV treatment is not without risk.[64] UV phototherapy is not indicated in young adults and children due to this risk of skin cancer with prolonged use or exposure.[17]

Alternative medicine

While several Chinese herbal medicines are intended for treating atopic eczema, no conclusive evidence shows that these treatments, taken by mouth or applied topically, reduce the severity of eczema in children or adults.[65]

Epidemiology

Since the beginning of the 20th century, many inflammatory skin disorders have become more common; AD is a classic example of such a disease. It now affects 15–30% of children and 2–10% of adults in developed countries, and in the United States has nearly tripled in the past 30–40 years.[9][66] Over 15 million American adults and children have AD.[67]

Research

Evidence suggests that IL-4 is central in the pathogenesis of AD.[68] Therefore, a rationale exists for targeting IL-4 with IL-4 inhibitors.[69] People with atopic dermatitis are more likely to have Staphylococcus aureus living on them.[70] The role this plays in pathogenesis is yet to be determined.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology (Cambridge University Press) 25 (7): 522–529. October 2000. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00698.x. ISBN 9780521570756. PMID 11122223. https://books.google.com/books?id=q8OZ4O_gjQUC&pg=PA10.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 "Handout on Health: Atopic Dermatitis (A type of eczema)". May 2013. http://www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Atopic_Dermatitis/default.asp.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 "Atopic dermatitis: skin-directed management". Pediatrics 134 (6): e1735–44. December 2014. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2812. PMID 25422009.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Atopic dermatitis: natural history, diagnosis, and treatment". ISRN Allergy 2014: 354250. 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/354250. PMID 25006501.

- ↑ Evidence-Based Dermatology. John Wiley & Sons. 2009. pp. 128. ISBN 9781444300178. https://books.google.com/books?id=SbsQij5xkfYC&pg=PA128.

- ↑ "Topical calcineurin inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: review and treatment recommendations". Paediatric Drugs 15 (4): 303–10. August 2013. doi:10.1007/s40272-013-0013-9. PMID 23549982.

- ↑ "Atopic Dermatitis" (in en). September 2019. https://www.niams.nih.gov/health-topics/atopic-dermatitis.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 "Atopic dermatitis: an overview". American Family Physician 86 (1): 35–42. July 2012. PMID 22962911. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/0701/p35.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 "Atopic Dermatitis". Medscape Reference. WebMD. 21 January 2014. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1049085-overview#showall.

- ↑ Lang, F, ed (2009). "Atopic Dermatitis". Encyclopedia of molecular mechanisms of diseases. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-67136-7.

- ↑ "Guidance on the diagnosis and clinical management of atopic eczema". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology 37 (Suppl 1): 7–12. May 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04336.x. PMID 22486763.

- ↑ "Assessment of clinical signs of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and recommendation". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 132 (6): 1337–47. December 2013. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.008. PMID 24035157.

- ↑ "The infra-auricular fissure: a bedside marker of disease severity in patients with atopic dermatitis". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 66 (6): 1009–10. June 2012. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.10.031. PMID 22583715. http://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(11)01188-1/abstract. Retrieved 2016-03-20.

- ↑ (in en) Problem-Based Medical Case Management. Hong Kong University Press. 2006-01-01. ISBN 9789622097759. https://books.google.com/books?id=sL0Cd-AnuNMC.

- ↑ "Atopic Dermatitis: Update for Pediatricians". Pediatric Annals 45 (8): e280–6. August 2016. doi:10.3928/19382359-20160720-05. PMID 27517355.

- ↑ "The effect of environmental humidity and temperature on skin barrier function and dermatitis". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 30 (2): 223–249. February 2016. doi:10.1111/jdv.13301. PMID 26449379.

- ↑ 17.00 17.01 17.02 17.03 17.04 17.05 17.06 17.07 17.08 17.09 17.10 17.11 17.12 17.13 17.14 17.15 17.16 "Atopic Dermatitis". The New England Journal of Medicine 384 (12): 1136–1143. March 2021. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2023911. PMID 33761208.

- ↑ "The Pathogenetic Effect of Natural and Bacterial Toxins on Atopic Dermatitis". Toxins 9 (1): 3. December 2016. doi:10.3390/toxins9010003. PMID 28025545.

- ↑ "Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases". The New England Journal of Medicine 365 (14): 1315–27. October 2011. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1011040. PMID 21991953.

- ↑ "News Feature: Cleaning up the hygiene hypothesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (7): 1433–1436. 2017. doi:10.1073/pnas.1700688114. PMID 28196925. Bibcode: 2017PNAS..114.1433S.

- ↑ "Atopic dermatitis". The New England Journal of Medicine 358 (14): 1483–94. April 2008. doi:10.1056/NEJMra074081. PMID 18385500.

- ↑ "Pet exposure and risk of atopic dermatitis at the pediatric age: a meta-analysis of birth cohort studies". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 132 (3): 616–622.e7. September 2013. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.04.009. PMID 23711545.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 "New insights into the epidemiology of childhood atopic dermatitis". Allergy 69 (1): 3–16. January 2014. doi:10.1111/all.12270. PMID 24417229.

- ↑ "Prevention of food and airway allergy: consensus of the Italian Society of Preventive and Social Paediatrics, the Italian Society of Paediatric Allergy and Immunology, and Italian Society of Pediatrics". The World Allergy Organization Journal 9: 28. 2016. doi:10.1186/s40413-016-0111-6. PMID 27583103.

- ↑ "How epidemiology has challenged 3 prevailing concepts about atopic dermatitis". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 118 (1): 209–13. July 2006. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.043. PMID 16815157. http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/861/2/revised_final_rostrum.pdf.

- ↑ "Dissecting the causes of atopic dermatitis in children: less foods, more mites". Allergology International 61 (2): 231–43. June 2012. doi:10.2332/allergolint.11-RA-0371. PMID 22361514.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Nonceliac gluten sensitivity". Gastroenterology 148 (6): 1195–204. May 2015. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.049. PMID 25583468. "Many patients with celiac disease also have atopic disorders. About 30% of patients' allergies with gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and mucosal lesions, but negative results from serologic (TG2 antibodies) or genetic tests (DQ2 or DQ8 genotype) for celiac disease, had reduced GI and atopic symptoms when they were placed on GFDs. These findings indicated that their symptoms were related to gluten ingestion.".

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: literature review". Journal of the American College of Nutrition 33 (1): 39–54. 2014. doi:10.1080/07315724.2014.869996. PMID 24533607. https://iris.unipa.it/bitstream/10447/90208/1/Journal of the Americal College of Nutrition 2014 33 39-54.pdf.

- ↑ "Skin colonization of Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis patients seen at the National Skin Centre, Singapore". International Journal of Dermatology 36 (9): 653–7. September 1997. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00290.x. PMID 9352404.

- ↑ "Staphylococcus aureus Exploits Epidermal Barrier Defects in Atopic Dermatitis to Trigger Cytokine Expression". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 136 (11): 2192–2200. November 2016. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.05.127. PMID 27381887.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Potential health impacts of hard water". International Journal of Preventive Medicine 4 (8): 866–75. August 2013. PMID 24049611.

- ↑ "Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 15 (1): 35–50. January 2016. doi:10.1038/nrd4624. PMID 26471366.

- ↑ "Type 2 immunity in the skin and lungs". Allergy 75 (7): 1582–1605. July 2020. doi:10.1111/all.14318. PMID 32319104.

- ↑ "Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 70 (2): 338–51. February 2014. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010. PMID 24290431.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis: a systematic review". The British Journal of Dermatology 158 (4): 754–65. April 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08412.x. PMID 18241277.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "The U.K. Working Party's Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. III. Independent hospital validation". The British Journal of Dermatology 131 (3): 406–16. September 1994. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08532.x. PMID 7918017.

- ↑ "Moisturizers for patients with atopic dermatitis" (PDF). Asian Pacific Journal of Allergy and Immunology 31 (2): 91–8. June 2013. PMID 23859407. http://apjai.digitaljournals.org/index.php/apjai/article/viewFile/1355/1135. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 "Non-pharmacologic therapies for atopic dermatitis". Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 13 (5): 528–38. October 2013. doi:10.1007/s11882-013-0371-y. PMID 23881511.

- ↑ "The role of vitamin D in atopic dermatitis". Dermatitis 26 (4): 155–61. 2015. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000128. PMID 26172483.

- ↑ "Vitamin D and atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Nutrition 32 (9): 913–20. September 2016. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2016.01.023. PMID 27061361. http://kumel.medlib.dsmc.or.kr/handle/2015.oak/32833.

- ↑ Lohner S, Decsi T. Role of Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in the Prevention and Treatment of Atopic Diseases. In: Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Sources, Antioxidant Properties and Health Benefits (edited by: Angel Catalá). NOVA Publishers. 2013. Chapter 11, pp. 1-24. (ISBN:978-1-62948-151-7)

- ↑ "Probiotics for treating eczema". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018 (11): CD006135. November 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006135.pub3. PMID 30480774.

- ↑ "Probiotics supplementation during pregnancy or infancy for the prevention of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis". Epidemiology 23 (3): 402–14. May 2012. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824d5da2. PMID 22441545.

- ↑ "Synbiotics for Prevention and Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials". JAMA Pediatrics 170 (3): 236–42. March 2016. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3943. PMID 26810481.

- ↑ "Public Health Advisory: Elidel (pimecrolimus) Cream and Protopic (tacrolimus) Ointment". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 10 May 2005. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm051760.htm.

- ↑ "Topical pimecrolimus for eczema". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD005500. October 2007. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005500.pub2. PMID 17943859. http://www.cochrane.org/CD005500/SKIN_topical-pimecrolimus-for-eczema.

- ↑ "Topical tacrolimus for atopic dermatitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD009864. July 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009864.pub2. PMID 26132597. PMC 6461158. http://www.cochrane.org/CD009864/SKIN_topical-tacrolimus-atopic-dermatitis.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Eucrisa for Eczema". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 14 December 2016. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm533371.htm.

- ↑ "Eucrisa (crisaborole) Ointment, 2%, for Topical Use. Full Prescribing Information". Anacor Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Palo Alto, CA 94303 USA. http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=5331.

- ↑ "The effects of treatment on itch in atopic dermatitis". Dermatologic Therapy 26 (2): 110–9. March–April 2013. doi:10.1111/dth.12032. PMID 23551368.

- ↑ "Neuroimmunological mechanism of pruritus in atopic dermatitis focused on the role of serotonin". Biomolecules & Therapeutics 20 (6): 506–12. November 2012. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2012.20.6.506. PMID 24009842.

- ↑ "Leukotriene receptor antagonists for eczema". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018 (10): CD011224. October 2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011224.pub2. PMID 30343498.

- ↑ "FDA approves new eczema drug Dupixent". US Food & Drug Administration. 28 March 2017. https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm549078.htm.

- ↑ "Adtralza EPAR". 20 April 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/adtralza. Text was copied from this source which is © European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ↑ "Drug Approval Package: ADBRY". US Food & Drug Administration. December 27, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2022/761180Orig1s000TOC.cfm. Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Eli Lilly's Phase III Atopic Dermatitis Drug Touts Significant Skin Clearance" (in en-US). https://www.biospace.com/article/eli-lilly-s-atopic-dermatitis-drug-achieves-skin-clearance-target/.

- ↑ "U.S. FDA Approves Pfizer's Cibinqo (abrocitinib) for Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis". Pfizer Inc. (Press release). 14 January 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ↑ "U.S. FDA Approves RINVOQ® (upadacitinib) to Treat Adults and Children 12 Years and Older with Refractory, Moderate to Severe Atopic Dermatitis". AbbeVie (Press release). Retrieved March 6, 2022.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 "Specific allergen immunotherapy for the treatment of atopic eczema". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (2): CD008774. February 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008774.pub2. PMID 26871981. PMC 8761476. http://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/bitstream/10044/1/31818/2/CD008774.pdf.

- ↑ "Interventions to reduce Staphylococcus aureus in the management of eczema". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2019 (10). October 2019. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003871.pub3. PMID 31684694.

- ↑ "Reversal of atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy and biomarkers for therapeutic response". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 128 (3): 583–93.e1–4. September 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.042. PMID 21762976.

- ↑ "The effect of ultraviolet (UV) A1, UVB and solar-simulated radiation on p53 activation and p21". The British Journal of Dermatology 152 (5): 1001–8. May 2005. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06557.x. PMID 15888160.

- ↑ "Phototherapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: a systematic review". Photodermatology, Photoimmunology & Photomedicine 23 (4): 106–12. August 2007. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0781.2007.00291.x. PMID 17598862.

- ↑ "Differential role of basal keratinocytes in UV-induced immunosuppression and skin cancer". Molecular and Cellular Biology 26 (22): 8515–26. November 2006. doi:10.1128/MCB.00807-06. PMID 16966369.

- ↑ "Chinese herbal medicine for atopic eczema". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9): CD008642. September 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008642.pub2. PMID 24018636.

- ↑ "Much atopy about the skin: genome-wide molecular analysis of atopic dermatitis". International Archives of Allergy and Immunology 137 (4): 319–25. August 2005. doi:10.1159/000086464. PMID 15970641.

- ↑ "Atopic Dermatitis". www.uchospitals.edu. 1 January 2015. http://www.uchospitals.edu/online-library/content=P01675.

- ↑ "IL-4 up-regulates epidermal chemotactic, angiogenic, and pro-inflammatory genes and down-regulates antimicrobial genes in vivo and in vitro: relevant in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis". Cytokine 61 (2): 419–25. February 2013. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2012.10.031. PMID 23207180. https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/IL-4_up-regulates_epidermal_chemotactic_angiogenic_and_pro-inflammatory_genes_and_down-regulates_antimicrobial_genes_in_vivo_and_in_vitro_relevant_in_the_pathogenesis_of_atopic_dermatitis/10762856.

- ↑ "Therapeutic strategies in extrinsic atopic dermatitis: focus on inhibition of IL-4 as a new pharmacological approach". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 19 (1): 87–96. January 2015. doi:10.1517/14728222.2014.965682. PMID 25283256.

- ↑ "Prevalence and odds of Staphylococcus aureus carriage in atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". The British Journal of Dermatology 175 (4): 687–95. October 2016. doi:10.1111/bjd.14566. PMID 26994362.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- "Atopic Dermatitis". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/atopic-dermatitis.

|