| COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom | |

|---|---|

Cumulative COVID-19 case rates per 100,000 population (whole pandemic) as of 29 January 2022 | |

Cumulative reported COVID-19 death rates[nb 1] per 100,000 population (whole pandemic) as of 30 January 2022 | |

| |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | United Kingdom |

| First outbreak | Wuhan, China |

| Index case | York, North Yorkshire |

| Arrival date | 31 January 2020(3 years, 2 months and 6 days ago)[1] |

| Date | As of 6 January 2022[update] |

| Confirmed cases | |

| Hospitalised cases | |

| Ventilator cases | 911 (active)[3] |

Deaths | |

| Fatality rate | 2.88%

|

| Vaccinations | |

| Government website | |

| UK Government[nb 3] Scottish Government Welsh Government Northern Ireland Department of Health | |

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies |

|---|

|

| (Part of the global COVID-19 pandemic) |

The COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom is a part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). In the United Kingdom, it has resulted in 24,311,933[2] confirmed cases and 211,155[2] deaths.

The number of cases is the second most in Europe and fourth-highest worldwide.[disputed ] The 211,155[2] deaths among people who had recently tested positive is the world's seventh-highest death toll and 28th-highest death rate by population.[disputed ][6][7] This is Europe's second-highest death toll after Russia, and 20th-highest death rate.[disputed ][7]

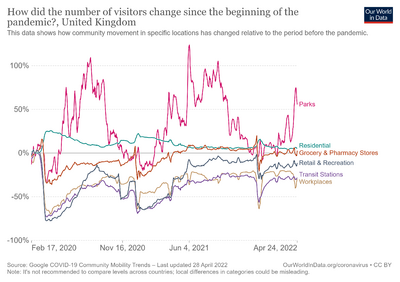

The virus began circulating in the country in early 2020, arriving primarily from travel elsewhere in Europe. Various sectors responded, with more widespread public health measures incrementally introduced from March 2020. The first wave was at the time one of the world's largest outbreaks. By mid-April the peak had been passed and restrictions were gradually eased. A second wave, with a new variant that originated in the UK becoming dominant, began in the autumn and peaked in mid-January 2021, and was deadlier than the first. The UK started a COVID-19 vaccination programme in early December 2020. Generalised restrictions were gradually lifted and were mostly ended by August 2021. A third wave, fuelled by the new Delta variant, began in July 2021, but the rate of deaths and hospitalisations was lower than with the first two waves – this being attributed to the mass vaccination programme. By early December 2021, the Omicron variant had arrived, and caused record infection levels.

The UK government and each of the three devolved governments (in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales) introduced public health and economic measures, including new laws, to mitigate its impact. A national lockdown was introduced on 23 March 2020 and lifted in May, being replaced with specific regional restrictions. Further nationwide lockdowns were introduced in autumn and winter 2020 in response to a surge in cases. Most restrictions were lifted during the Delta-variant-driven third wave in mid-2021. The "winter plan" reintroduced some rules in response to the Omicron variant in December 2021. Economic support was given to struggling businesses including a furlough scheme for employees.

As well as the major strain on the UK's healthcare service, the pandemic has had a severe impact on the UK's economy, caused major disruptions to education and had far-reaching impacts on society and politics.

History[edit | edit source]

Origin[edit | edit source]

On 12 January 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed that a novel coronavirus was the cause of a respiratory illness in a cluster of people in Wuhan City, Hubei, China, which was reported to the WHO on 31 December 2019.[8][9] The case fatality ratio for COVID-19 has been much lower than SARS of 2003,[10][11] but the transmission has been significantly greater, with a significant total death toll.[12][10]

Scientists used statistical analysis of data from genetic sequencing, combined with epidemiological and estimated travel data, to estimate the source locations of the virus in the UK up to the beginning of March 2020, and following the initial importations which were likely from China or elsewhere in Asia. From this analysis they estimated that about 33% were from Spain, 29% from France, 12% from Italy and 26% from elsewhere.[13]

First wave[edit | edit source]

Though later reporting indicated that there may have been some cases dating from late 2019,[14][15] COVID-19 was confirmed to be spreading in the UK by the end of January 2020[16] with the first confirmed deaths in March.[17] Subsequent epidemiological analysis showed that over 1000 lineages of SARS-CoV-2 entered the UK in early 2020 from international travellers, mostly from outbreaks elsewhere in Europe, leading to numerous clusters that overwhelmed contact tracing efforts.[13] Limited testing and surveillance meant during the early weeks of the pandemic, case numbers were underestimated, obscuring the extent of the outbreak.[18][19]

A legally-enforced Stay at Home Order, or lockdown, was introduced on 23 March,[20] banning all non-essential travel and contact with other people, and shut schools, businesses, venues and gathering places. People were told to keep apart in public. Those with symptoms, and their households, were told to self-isolate, while those considered at highest risk were told to shield. The health services worked to raise hospital capacity and established temporary critical care hospitals, but initially faced some shortages of personal protective equipment. By mid-April it was reported that restrictions had "flattened the curve" of the epidemic and the UK had passed its peak[21] after 26,000 deaths.[22] The UK's overall death toll and by population surpassed that of Italy on 3 May, making the UK the worst affected country in Europe at the time.[23] Restrictions were steadily eased across the UK in late spring and early summer that year.[24][25][26][27][28][29] The UK's epidemic in early 2020 was at the time one of the largest worldwide.[13]

Second wave[edit | edit source]

By the autumn, COVID-19 cases were again rising.[30] This led to the introduction of social distancing measures and some localised restrictions.[31][32][33][34][35][36] Larger lockdowns took place in all of Wales, England and Northern Ireland later that season.[37][38][39] In both England and Scotland, tiered restrictions were introduced in October,[40] and England went into a month-long lockdown during November followed by new tiered restrictions in December.[41] Multi-week 'circuit-breaker' lockdowns were imposed in Wales[42] and Northern Ireland.[43] A new variant of the virus is thought to have originated in Kent around September 2020.[44][45] Once restrictions were lifted, the novel variant rapidly spread across the UK.[46] Its increased transmissibility contributed to a continued increase in daily infections that surpassed previous records.[47] The healthcare system had come under severe strain by late December.[48] Following a partial easing of restrictions for Christmas,[49] all of the UK went into a third lockdown.[50] The second wave peaked in mid-January with over 1,000 daily deaths, before declining into the summer.[51]

The first COVID-19 vaccine was approved and began being deployed across the UK in early December;[52][53] with a staggered rollout prioritising the most vulnerable and then moving to progressively younger age groups.[54] The UK was the first country to do so, and in early 2021 its vaccination program was one of the fastest in the world.[53] By August 2021, more than 75% of adults in the UK were fully vaccinated against COVID-19.[55] Quarantine rules for all incoming travellers were introduced for the first time in late January.[56] Restrictions began to ease from late February onwards and almost all had ended in Great Britain by August.[57][58][59][60]

Third wave[edit | edit source]

A third wave of daily infections began in July 2021 due to the arrival and rapid spread of the highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant.[61] However, mass vaccination continued to keep deaths and hospitalisations at much lower levels than in previous waves.[62][63] Infection rates remained high and hospitalisations and deaths rose into the autumn.[64][65] In December, the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant was confirmed to have arrived and begun spreading widely in the community, particularly in London,[66][67] driving a further increase in cases[68] that surpassed previous records, although the true number of infections was thought to be higher.[69][70] It became mandatory for people to show proof of full vaccination or proof that they are not infected to enter certain indoor hospitality and entertainment venues.[71] On 9 January 2022, the UK became the seventh country worldwide to pass 150,000 reported[nb 1] COVID-19 deaths.[72]

All remaining legally enforced COVID-19 related restrictions concluded in Northern Ireland and England during February,[73][74][75] with that step being taken in Scotland (partially extended into April)[76] and Wales by the end of March.[77][78] Cases rose following the relaxation of restrictions.[79][80]

Impacts[edit | edit source]

There has been some disparity between the outbreak's severity in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland – health-care in the UK is devolved, each constituent country having its own publicly-funded healthcare system run by devolved governments.[81][82][83]

Health and life expectancy[edit | edit source]

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the largest fall in life expectancy in England since records began in 1981.[84][85] On average, British COVID-19 victims lost around a decade of life; the last time deaths rose so sharply in the UK was during World War II.[86] In 2020, the disease was the leading cause of death among men, and second leading cause among women.[84]

Research suggests over 1 million people in the UK have had Long COVID, with the majority reporting substantial impacts on day-to-day life.[87][88] Professor Danny Altmann of Imperial College London said, “It’s kind of an anathema to me that we’ve kind of thrown in the towel on control of Omicron wave infections and have said ‘it’s endemic, and we don’t care any more, because it’s very benign’,” he said. “It just isn’t. And there are new people joining the long Covid support groups all the time with their disabilities. It’s really not OK, and it’s heartbreaking.”[89]

The pandemic's major impact on the country's healthcare system, leading to long waiting lists for medical procedures and ambulances, also led to an indirect increase in deaths from other conditions.[90] It also had a major mental health impact.[91]

In August 2021, a report from Age UK found that 27% of people over 60 could not walk as far and 25% were living in more physical pain earlier this year compared to the start of the pandemic. 54% of older people felt less confident attending a hospital appointment, and 37% of older people felt less confident going to a GP surgery.[92]

Education[edit | edit source]

Research by The Sunday Times reported that in 2021, the proportion of private school pupils receiving A*, a mark for exceptional achievement, was 39.5 per cent, rising from 16.1 per cent in 2019.[93] The highest record in terms of increase came from the North London Collegiate School, where senior fees could surpass £21,000 a year and the proportion of A* grades rose from 33.8 per cent in 2019 to 90.2 per cent in the summer of 2021. At 25 schools, the number of A* grades trebled or even quadrupled. These and other findings lead MPs to call for an inquiry into the "manipulation" of the exam system during the COVD-19 crisis.

Economy[edit | edit source]

The pandemic was widely disruptive to the economy of the United Kingdom, with most sectors and workforces adversely affected. Some temporary shutdowns became permanent; some people who were furloughed were later made redundant.[94][95] The economic disruption has had a significant impact on people's mental health—with particular damage to the mental health of foreign-born men whose work hours have been reduced/eliminated.[96]

Society[edit | edit source]

The pandemic has had far-reaching consequences in the country that go beyond the spread of the disease itself and efforts to quarantine it, including political, cultural, and social implications.

Spread to other countries and territories[edit | edit source]

Sophie Grégoire Trudeau, the wife of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, tested positive for COVID-19 upon her return from WE Day events in the UK; on 12 March 2020 the Trudeau family entered two weeks of self-isolation.[97] The first patient in Mauritius was a 59-year-old man who returned from the United Kingdom on 7 March 2020. When he arrived in Mauritius, the Mauritian had no symptoms.[98] Other cases of the novel coronavirus resulting from travel to the UK were subsequently reported in India[99][100] and Nigeria.[101]

On 16 June 2020, it was widely reported in British media that New Zealand's first COVID-19 cases in 24 days were diagnosed in two British women, both of whom had travelled from the UK and were given special permission to visit a dying parent. The women had entered the country on 7 June, after first flying into Doha and Brisbane.[102]

A 2021 study suggested that the SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant which was first detected in Kent is thought to have began its spread to many countries internationally from flights originating in London in late 2020.[103]

Statistics[edit | edit source]

As of 20 December 2021, there had been 11.4 million confirmed cases – the most in Europe and fourth-highest worldwide. By that date there had been 211,155[2] deaths among people who had recently tested positive – the world's seventh-highest death toll and 28th-highest death rate by population.[104] This is Europe's second-highest death toll after Russia, and the 20th-highest death rate worldwide.[104] Since early 2021 the UK has had one of the world's highest testing rates.[105][106]

Mathematical modelling and government response[edit | edit source]

Reports from the Medical Research Council's Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis at Imperial College, London have been providing mathematically calculated estimates of cases and case fatality rates.[107][108] In February 2020, the team at Imperial College, led by epidemiologist Neil Ferguson, estimated about two-thirds of cases in travellers from China were not detected and that some of these may have begun "chains of transmission within the countries they entered".[109][110][111] They forecast that the new type of coronavirus could infect up to 60% of the UK's population, in the worst-case scenario.[112]

In a paper on 16 March, the Imperial College team provided detailed forecasts of the potential impacts of the epidemic in the UK and US.[113][114] It detailed the potential outcomes of an array of 'non-pharmaceutical interventions'. Two potential overall strategies outlined were: mitigation, in which the aim is to reduce the health impact of the epidemic but not to stop transmission completely; and suppression, where the aim is to reduce transmission rates to a point where case numbers fall. Until this point, government actions had been based on a strategy of mitigation, but the modelling predicted that while this would reduce deaths by approximately 2/3, it would still lead to approximately 250,000 deaths from the disease and the health systems becoming overwhelmed.[113] On 16 March, the Prime Minister announced changes to government advice, extending self-isolation to whole households, advising social distancing particularly for vulnerable groups, and indicating that further measures were likely to be required in the future.[115][114] A paper on 30 March by the Imperial College group estimated that the lockdown would reduce the number of dead from 510,000 to less than 20,000. This paper and others relied on data from European countries including the UK to estimate that the combined non-pharmaceutical interventions reduced the reproduction number of the virus by 67-87%, enough to stop infections from growing.[116][117] However, followup work concluded that the effectiveness of interventions was lower in later waves of infections.[118]

In April 2020, biostatistician Professor Sheila Bird said the delay in the reporting of deaths from the virus meant there was a risk of underestimating the steepness of the rising epidemic trend.[119]

In December 2021 scientists from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine predicted that Omicron could cause from 25,000 to 75,000 deaths in England over the five months to April 2022 unless there were more stringent restrictions, and would probably become the dominant variant by the end of 2021.[120]

See also[edit | edit source]

- COVID-19 pandemic in England

- COVID-19 pandemic in Northern Ireland

- COVID-19 pandemic in Scotland

- COVID-19 pandemic in Wales

- COVID-19 pandemic in the British Overseas Territories

- COVID-19 pandemic in Guernsey

- COVID-19 pandemic in Jersey

- COVID-19 pandemic in the Isle of Man

- COVID-19 pandemic impact on retail (United Kingdom)

- Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on education in the United Kingdom

- COVID-19 vaccination programme in the United Kingdom

- British government response to the COVID-19 pandemic

- COVID-19 pandemic in Europe

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Deaths within 28 days of a positive test by date reported. Does not include the death of one British citizen on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship (see COVID-19 pandemic on cruise ships), or the 84 recorded deaths in the British Overseas Territories and Crown dependencies.

- ↑ Deaths with COVID-19 on the death certificate by date of death.

- ↑ Daily updates occur around 4 pm UTC.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Lillie, Patrick J.; Samson, Anda; Li, Ang; Adams, Kate; Capstick, Richard; Barlow, Gavin D.; Easom, Nicholas; Hamilton, Eve; Moss, Peter J.; Evans, Adam; Ivan, Monica (28 February 2020). "Novel coronavirus disease (Covid-19): The first two patients in the UK with person to person transmission". Journal of Infection. 80 (5): 600–601. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.020. ISSN 0163-4453. PMC 7127394. PMID 32119884. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Ritchie, Hannah; Mathieu, Edouard; Rodés-Guirao, Lucas; Appel, Cameron; Giattino, Charlie; Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban; Hasell, Joe; Macdonald, Bobbie; Beltekian, Diana; Dattani, Saloni; Roser, Max (2020–2022). "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK". GOV.UK. Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ↑ Office for National Statistics (8 April 2021). "Deaths registered weekly in England and Wales, provisional". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ↑ "SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England Technical Briefing 18" (PDF). Public Health England. 9 July 2021. p. 11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

Case fatality is not comparable across variants as they have peaked at different points in the pandemic, and so vary in background hospital pressure, vaccination availability and rates and case profiles, treatment options, and impact of reporting delay, among other factors

This article incorporates text published under the British Open Government Licence v3.0:

This article incorporates text published under the British Open Government Licence v3.0:

- ↑ "Coronavirus (Covid-19) in the United Kingdom-Deaths in the United Kingdom". UK Government. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Mortality Analyses". Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ↑ Elsevier. "Novel Coronavirus Information Center". Elsevier Connect. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ Reynolds, Matt (4 March 2020). "What is coronavirus and how close is it to becoming a pandemic?". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Archived from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Crunching the numbers for coronavirus". Imperial News. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ "High consequence infectious diseases (HCID); Guidance and information about high consequence infectious diseases and their management in England". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020.

- ↑ "World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists – Coronavirus". wfsahq.org. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 du Plessis, Louis; McCrone, John T.; Zarebski, Alexander E.; Hill, Verity; Ruis, Christopher; Gutierrez, Bernardo; Raghwani, Jayna; Ashworth, Jordan; Colquhoun, Rachel; Connor, Thomas R.; Faria, Nuno R. (12 February 2021). "Establishment and lineage dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the UK". Science. 371 (6530): 708–712. Bibcode:2021Sci...371..708D. doi:10.1126/science.abf2946. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 7877493. PMID 33419936.

- ↑ "Covid started a year ago – but did this bricklayer bring it to UK sooner?". Metro. 17 November 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus doctor's diary: the strange case of the choir that coughed in January". BBC News. 10 May 2020. Archived from the original on 7 March 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ Ball, Tom; Wace, Charlotte (31 January 2020). "Hunt for contacts of coronavirus-stricken pair in York". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Man in 80s is second person to die of virus in UK". BBC News. 7 March 2020. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ↑ Pollock, Allyson M.; Roderick, Peter; Cheng, K. K.; Pankhania, Bharat (30 March 2020). "Covid-19: why is the UK government ignoring WHO's advice?". BMJ. 368: m1284. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1284. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32229543. S2CID 214702525. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ "Into the fog: How Britain lost track of the coronavirus". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ↑ "Boris Johnson orders three-week lockdown of UK to tackle coronavirus spread". ITV News. 23 March 2020. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- ↑ "UK's social distancing has flattened COVID-19 curve: science official". Reuters. 15 April 2020. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ "UK coronavirus deaths pass 26,000". BBC News. 29 April 2020. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- ↑ Mahase, Elisabeth (6 May 2020). "Covid-19: UK death toll overtakes Italy's to become worst in Europe". BMJ. 369: m1850. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1850. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32376760. S2CID 218533792. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ "PM address to the nation on coronavirus: 10 May 2020". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Scottish lockdown easing to begin on Friday". BBC News. 28 May 2020. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- ↑ "Non-essentials shops in NI can reopen from Friday". ITV News. 8 June 2020. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ↑ "As it happened: Thousands flock to reopened shops in England". BBC News. 15 June 2020. Archived from the original on 5 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ↑ "Shops reopen with strict social distancing measures". BBC News. 22 June 2020. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ↑ "Queues form as doors open for retail return". BBC News. 29 June 2020. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ↑ "Covid updates: UK records highest daily Covid deaths since 1 July". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ "Children will stay part of rule of six, says Gove". BBC News. 12 September 2020. Archived from the original on 13 September 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ↑ "Covid: New restrictions in North West, Midlands, and West Yorkshire". BBC News. 18 September 2020. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ↑ "Pubs in England to close at 10pm amid Covid spread". BBC News. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ↑ "Pubs in Wales to close at 22:00 from Thursday". BBC News. 22 September 2020. Archived from the original on 24 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ↑ "Alcohol-only pubs reopen in Northern Ireland". BBC News. 23 September 2020. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ↑ Covid: Ban on meeting in houses extended across Scotland Archived 23 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine 22 September 2020 BBC. Retrieved 23 September 2020

- ↑ "Schools to close and tight new hospitality rules in Northern Ireland". BBC News. 14 October 2020. Archived from the original on 13 October 2020. Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- ↑ "Covid: Wales to go into 'firebreak' lockdown from Friday". BBC News. 19 October 2020. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

- ↑ Covid-19: PM announces four-week England lockdown Archived 31 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine 1 November 2020 BBC. Retrieved 5 November 2020

- ↑ "Covid-19: Nicola Sturgeon unveils Scotland's restriction levels". BBC News. 29 October 2020. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "England's Covid tier system explained... with cake". BBC News. 17 November 2020. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ Morris, Steven (19 October 2020). "What are the rules of Wales's circuit breaker coronavirus lockdown?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "NI enters two-week circuit breaker lockdown". ITV News. 27 November 2020. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "Covid-19: New coronavirus variant is identified in UK". BMJ. 16 December 2020. doi:10.1136/bmj.m4857. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ↑ New and Emerging Respiratory Virus Threats Advisory Group (18 December 2020). "NERVTAG meeting on SARS-CoV-2 variant under investigation: VUI-202012/01". Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ↑ Kraemer, Moritz U. G.; Hill, Verity; Ruis, Christopher; Dellicour, Simon; Bajaj, Sumali; McCrone, John T.; Baele, Guy; Parag, Kris V.; Battle, Anya Lindström; Gutierrez, Bernardo; Jackson, Ben (20 August 2021). "Spatiotemporal invasion dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 emergence". Science. 373 (6557): 889–895. Bibcode:2021Sci...373..889K. doi:10.1126/science.abj0113. PMID 34301854. S2CID 236209853. Archived from the original on 5 October 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ↑ "Covid-19: UK reports a record 55,892 daily cases". BBC News. 31 December 2020. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ↑ "Overwhelmed NHS hospitals diverting patients experts warn of third wave Archived 27 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine". The Week UK. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

"Covid: 'Nail-biting' weeks ahead for NHS, hospitals in England warn Archived 1 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. 1 January 2021. from the original on 1 January 2021 Retrieved 1 January 2021.

Campbell, Denis (27 December 2020). "Hospitals in England told to free up all possible beds for surging Covid cases Archived 31 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077 Archived 16 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

"Pressure on hospitals 'at a really dangerous point' Archived 24 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. 18 December 2020. Archived from the original on 18 December 2020 Retrieved 1 January 2021.

"Covid rule-breakers 'have blood on their hands Archived 4 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine'". BBC News. 31 December 2020. Archived from the original on 31 December 2020 Retrieved 1 January 2021. - ↑ "Covid-19: Christmas rules tightened for England, Scotland and Wales". BBC News. 20 December 2020. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: NI facing six-week lockdown from 26 December Archived 8 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 17 December 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

"Covid: Wales locks down as Christmas plans cut Archived 5 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. 19 December 2020. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

"Covid: New lockdown for England amid 'hardest weeks Archived 4 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine'". BBC News. 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 5 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

"Covid in Scotland: Scots ordered to stay at home in new lockdown Archived 4 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine". BBC News. 4 January 2021. Archived from the original on 4 January 2021. Retrieved 4 January 2021. - ↑ "COVID-19: Deaths in England and Wales down 99% from second wave peak". Sky News. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ "Covid: First batch of vaccines arrives in the UK". BBC News. 3 December 2020. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Covid-19 vaccine: First person receives Pfizer jab in UK". BBC News. 8 December 2020. Archived from the original on 8 December 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

- ↑ "Covid: Vaccine given to 15 million in UK as PM hails 'extraordinary feat'". BBC News. 14 February 2021. Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ↑ "Covid-19: More than 75% of UK adults now double-jabbed". BBC News. 10 August 2021. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Priti Patel says UK should have closed borders in March 2020" Archived 6 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News, 20 January 2021.

- ↑ "What's the roadmap for lifting lockdown? - BBC News". 23 February 2021. Archived from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ↑ "19 July: England Covid restrictions ease as PM urges caution". BBC News. 19 July 2021. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ↑ "Covid: Pubs busy as most rules end in Wales". BBC News. 7 August 2021. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ↑ "Covid in Scotland: 'Right moment' to lift restrictions, says Sturgeon". BBC News. 9 August 2021. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ↑ Callaway, Ewen (22 June 2021). "Delta coronavirus variant: scientists brace for impact". Nature. 595 (7865): 17–18. Bibcode:2021Natur.595...17C. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-01696-3. PMID 34158664. S2CID 235609029. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) latest insights - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ↑ "'We are a petri dish': world watches UK's race between vaccine and virus". The Guardian. 2 July 2021. Archived from the original on 8 July 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ↑ "Why Britons are tolerating sky-high Covid rates – and why this may not last". The Guardian. 15 October 2021. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "UK records highest Covid deaths since March". The Guardian. 19 October 2021. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ Iacobucci, Gareth (21 December 2021). "Covid-19: Government ignores scientists' advice to tighten restrictions to combat omicron". BMJ. 375: n3131. doi:10.1136/bmj.n3131. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 34933906. S2CID 245355478. Archived from the original on 4 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ "Covid: Omicron spreading in the community, Javid confirms". BBC News. 6 December 2021. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ↑ "Covid: Two jabs 'not enough to stop Omicron infection' and highest UK cases since January". BBC News. 10 December 2021. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 10 December 2021.

- ↑ "Covid: UK reports highest daily cases since the pandemic began". BBC News. 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ↑ "Covid-19: A record day for cases - what does it tell us?". BBC News. 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ↑ "Covid passports: Where will I need a vaccine pass and how do I get one?". BBC News. BBC. BBC. 8 December 2021. Archived from the original on 10 December 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ↑ "UK first country in Europe to pass 150,000 Covid deaths, figures show". The Guardian. 8 January 2022. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ↑ Limb, Matthew (28 February 2022). "Covid-19: Is the government dismantling pandemic systems too hastily?". BMJ. 376: o515. doi:10.1136/bmj.o515. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 35228255. S2CID 247146564. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ "Covid-19: Remaining restrictions in NI are lifted". BBC News. 15 February 2022. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- ↑ "Covid: England ending isolation laws and mass free testing". BBC News. 21 February 2022. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ↑ "Covid in Scotland: Mask rules will stay in force until April". BBC News. 15 March 2022. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ↑ "Covid in Scotland: All legal restrictions to end on 21 March". BBC News. 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ↑ "Covid in Wales: Mass testing pandemic rules to be axed". BBC News. 4 March 2022. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ↑ "Covid infections rising again across UK - ONS". BBC News. 11 March 2022. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ Russell, Peter (10 March 2022). "New COVID Infections Up By 46% Across the UK". Medscape. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

for the UK over the last 7 days, the number of new infections was up 46.4%, deaths were up 19.5%, and patients admitted to hospital was up 12.2% ... 1 in 30 People Infected ... Zoe R is 1.1

- ↑ "NHS now four different systems". BBC News. 2 January 2008. Archived from the original on 3 April 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ "'Huge contrasts' in devolved NHS". BBC News. 28 August 2008. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ↑ Greer, Scott L. (10 June 2016). "Devolution and health in the UK: policy and its lessons since 1998". British Medical Bulletin. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

Since devolution in 1998, the UK has had four increasingly distinct health systems, in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Iacobucci, Gareth (27 September 2021). "Covid-19: England sees biggest fall in life expectancy since records began in wake of pandemic". BMJ. 374: n2291. doi:10.1136/bmj.n2291. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 34580075. S2CID 237637504. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "Covid-19: Life expectancy is down but what does this mean?". BBC News. 23 September 2021. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "Covid-19: Behind the death toll". Full Fact. 26 March 2021. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "Long Covid: More than two million in England may have suffered, study suggests". BBC News. 24 June 2021. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ Long Covid could create a generation affected by disability, expert warns Archived 13 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian

- ↑ "Unexplained surge in non-Covid deaths triggers calls for probe". The Week UK. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ↑ Scott, Ellen (23 March 2021). "The mental health impact of Covid will be felt long after lockdown lifts". Metro. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 20 October 2021.

- ↑ "'Big implications' for social care as study reveals impact of pandemic on older people's mobility". Home Care Insight. 3 August 2021. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ↑ Rodrigues, Nick; Griffiths, Sian; McCall, Alastair (5 February 2022). "Private schools 'gamed' Covid rules to give their pupils more top A-levels". The Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ "Coronavirus and the impact on output in the UK economy – Office for National Statistics". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ↑ Walker, Andrew (10 June 2020). "UK economy virus hit among worst of leading nations". BBC News. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ↑ Shen, Jing; Bartram, David (2020). "Fare Differently, Feel Differently: Mental Well-Being of UK-Born and Foreign-Born Working Men during the COVID-19 Pandemic". European Societies. 23: S370–S383. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1826557. S2CID 225166709.

- ↑ Tasker, John Paul (12 March 2020). "Sophie Grégoire Trudeau's coronavirus infection comes after attending U.K. event". CBC News. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ Momplé, Stéphanie (19 March 2020). "Covid-19 : trois Mauriciens testés positifs ; "zot pe gayn tou tretman ki bizin", rassure le PM". Le Défi Media Group. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ "Kolkata on Covid-19 map, teen back from UK tests positive". The Times of India. Television News Network. 18 March 2020. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ "COVID-19 LIVE: Two new cases confirmed in Telangana, India tally crosses 250". The New Indian Express. Express Publications. 19 March 2020. Archived from the original on 19 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus – Virus: Nigeria don confam new Covid-19 outbreak – See wetin we know so far". BBC News (in Naijá). 17 March 2020. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ "New Zealand's first Covid cases in 24 days came from UK". BBC News. 16 June 2020. Archived from the original on 17 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ↑ O'Toole, Áine; Hill, Verity; Pybus, Oliver G.; Watts, Alexander; Bogoch, Issac I.; Khan, Kamran; Messina, Jane P.; Tegally, Houriiyah; Lessells, Richard R.; Giandhari, Jennifer; Pillay, Sureshnee (17 September 2021). "Tracking the international spread of SARS-CoV-2 lineages B.1.1.7 and B.1.351/501Y-V2 with grinch". Wellcome Open Research. 6: 121. doi:10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16661.2. ISSN 2398-502X. PMC 8176267. PMID 34095513.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 "Coronavirus (Covid-19) in the United Kingdom: Deaths in the United Kingdom". Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021.

- ↑ "Daily COVID-19 tests per thousand people". Our World in Data. 1 January – 16 December 2021. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ↑ "Total COVID-19 tests per 1,000 people". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022. Frequently updated

- ↑ Mahase, Elisabeth (10 February 2020). "Coronavirus: NHS staff get power to keep patients in isolation as UK declares "serious threat"". British Medical Journal. 368: m550. doi:10.1136/bmj.m550. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 32041792. S2CID 211077551. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ↑ Imai, Natsuko; Dorigatti, Ilaria; Cori, Anne; Donnelly, Christl; Riley, Steven; Ferguson, Neil M. (22 January 2020). "Report 2 - Estimating the potential total number of novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) cases in Wuhan City, China". Imperial College London - MRC Centre for Global Infectious Disease Analysis. Archived from the original on 25 January 2020.

- ↑ van Elsland, Sabine L.; Wighton, Kate (22 February 2020). "Two thirds of COVID-19 cases exported from mainland China may be undetected". Imperial College London - News. Archived from the original on 6 March 2020.

- ↑ MacKenzie, Debora (24 February 2020). "Covid-19: Our chance to contain the coronavirus may already be over". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020.

- ↑ "COVID-19 strains global monitoring systems to the extreme". The Japan Times. 26 February 2020. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on 12 July 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ↑ Petter, Olivia (13 February 2020). "Prevent spread of coronavirus on with 'less hugging and kissing', says virologist". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2020.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team (16 March 2020). "Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID19 mortality and healthcare demand" (PDF). Imperial College London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 Lintern, Shaun (17 March 2020). "World holds its breath and looks to China for clues on what coronavirus pandemic does next". The Independent. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: PM says everyone should avoid office, pubs and travelling". BBC News. 16 March 2020. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ↑ Ferguson, Neil (30 March 2020). "COVID-19 Europe estimates and NPI impact" (PDF). Imperial College London, www.imperial.ac.uk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2020. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ↑ Brauner, Jan M.; Mindermann, Sören; Sharma, Mrinank; Johnston, David; Salvatier, John; Gavenčiak, Tomáš; Stephenson, Anna B.; Leech, Gavin; Altman, George; Mikulik, Vladimir; Norman, Alexander John (19 February 2021). "Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19". Science. 371 (6531): eabd9338. doi:10.1126/science.abd9338. hdl:10044/1/86864. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 7877495. PMID 33323424.

- ↑ Sharma, Mrinank; Mindermann, Sören; Rogers-Smith, Charlie; Leech, Gavin; Snodin, Benedict; Ahuja, Janvi; Sandbrink, Jonas B.; Monrad, Joshua Teperowski; Altman, George; Dhaliwal, Gurpreet; Finnveden, Lukas (5 October 2021). "Understanding the effectiveness of government interventions against the resurgence of COVID-19 in Europe". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 5820. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12.5820S. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26013-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 8492703. PMID 34611158.

- ↑ Barr, Caelainn; Duncan, Pamela; McIntyre, Niamh (4 April 2020). "Why what we think we know about the UK's coronavirus death toll is wrong". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 April 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2020.

- ↑ Ambrose, Tom (11 December 2021). "Omicron could cause 75,000 deaths in England by end of April [2022], say scientists". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 January 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

Further reading[edit | edit source]

- Arbuthnott, George, and Calvert, Jonathan, Failures of State: The Inside Story of Britain's Battle with Coronavirus (Harper Collins, 2021).

- Horton, Richard C. (2021). The COVID-19 catastrophe : what's gone wrong and how to stop it happening again (Second ed.). Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. ISBN 9781509549092. OCLC 1249439266.

- Mosley, Michael (2020). COVID-19 : everything you need to know about the Corona Virus and the race for the vaccine (First ed.). New York: Atria Books. ISBN 9781982164744. OCLC 1156472581.

- Honigsbaum, Mark (2020). The pandemic century : a history of global contagion from the Spanish flu to Covid-19 (Updated and revised ed.). London: W. H. Allen & Co. ISBN 9780753558287.

with new chapter and epilogue

- Honigsbaum, Mark (2019). The pandemic century : one hundred years of panic, hysteria and hubris. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 9781787381216.

A century of pandemics, from the Spanish flu to Zika

- Honigsbaum, Mark (2019). The pandemic century : one hundred years of panic, hysteria and hubris. London: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 9781787381216.

External links[edit | edit source]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom |

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19)". NHS England. 2 June 2020. Archived from the original on 2 March 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- "Coronavirus (COVID-19): what you need to do [in England]". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 14 September 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- "The Health Protection (Coronavirus) Regulations 2020". Government of the United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- "Advice on COVID-19 (coronavirus)". Health and Social Care (Northern Ireland). Archived from the original on 27 February 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- "Coronavirus | United Kingdom". worldometers.info. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- COVID-19 United Kingdom government statistics Archived 13 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- Variants of concern or under investigation — weekly update. Public Health England (Report). Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2022.