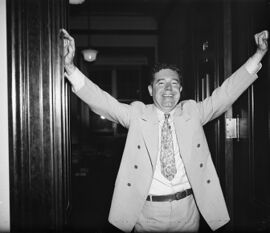

| Huey Pierce Long, Jr. | |

| |

U.S. Senator from Louisiana

| |

| In office January 25, 1932 – September 10, 1935 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Ransdell |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Rose McConnell Long |

| In office May 21, 1928 – January 25, 1932 | |

| Preceded by | Oramel H. Simpson |

| Succeeded by | Alvin Olin King |

| Born | August 30, 1893 Winnfield, Louisiana |

| Died | September 10, 1935 Baton Rouge, Louisiana |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democrat |

| Spouse(s) | Rose McConnell Long |

| Children | Three:

Rose Long (1917–2006) |

| Alma mater | Oklahoma Baptist University University of Oklahoma Tulane University |

| Religion | Baptist |

Huey Pierce Long, Jr. (August 30, 1893 – September 10, 1935), nicknamed Kingfish, was a powerful far-left American politician in the 1920s and 1930s who built a ruthless Democratic machine in Louisiana as governor (1928–32) and U.S. Senator (1932–35). His base was among angry poor whites, both Protestants and Roman Catholics (called "Rednecks" by the middle class enemies of Long).

A left-wing populist who fought the rich and promised "Every Man a King," he was preparing to run for president—either in 1940 when Franklin Delano Roosevelt was expected to retire, or perhaps to challenge FDR's reelection in 1936 in alliance with radio's influential Catholic priest Father Charles Coughlin. However, Long was assassinated in 1935 by the young physician Carl Weiss, the son-in-law of a political enemy, Louisiana 16th Judicial District Judge Benjamin Pavy.

Although called a "fascist", Long shunned ideology of all sorts, and his dictatorship by patronage, far from being alien, was the apogee of what many American machine politicians have attempted. Pernicious and impracticable as was his leftist Share-Our-Wealth plan, its objective of plenty for all was as intrinsically American as was the title "Kingfish." Debate remains as to whether he was a dictator, demagogue, messiah or populist; a friend of American values or an enemy?

Contents

Early career[edit]

Long was born in Winnfield north of Alexandria, Louisiana, in the piney woods region that had a strong Populist heritage. His father, a farmer, owned a medium-size farm, lived plainly but comfortably but managed to send six children to college. The family background was culturally meager and was most strongly marked by pious Southern Baptist evangelicalism and by a Populist animosity toward the wealth and sophistication of the planter class and of "evil" New Orleans. Huey became a salesman after completing his public schooling and married Rose McConnell in 1912. There was something of the confidence man about Long at every stage of his career. As a traveling salesman, whether promoting a cooking shortening called "Cottolene" by staging somewhat fixed baking contests (one of which was won by his future wife), or selling a patent-medicine nostrum called "The Wine of Cardui," Long sometimes seems a figure out of Southwestern humor, a kind of second cousin to Mark Twain's Duke and Dauphin.

After finishing the three-year program at Tulane Law School in less than one year, he was admitted to the bar of Louisiana in 1914. He practiced law in Shreveport for the next few years, having secured deferment from military service during World War I.

In 1918, Long narrowly won election to the Third District seat on the three-member Railroad Commission (renamed Public Service Commission after 1921). Both as member and as chairman (1922–1926), Long gained fame by his vocal battles with "the interests" which, he asserted, controlled state government, e.g., the Standard Oil Company, telephone companies, and other public utilities.

Governor[edit]

In the 1924 primary for governor, which was dominated by religious issues focusing on the activities of the Ku Klux Klan,[1] Long ran third in a three-man race.

The Klan collapsed in the late 1920s, so that the 1928 contest revolved around those economic and class issues on which Huey's strength rested.

Long secured an easy victory in the gubernatorial primary in 1928, defeated the opposition's attempt to impeach him in 1929, and midway in his term of office (1930) won his race for the U.S. Senate. However, just as he had promised, he did not take his senate seat until January 1932, by which time his hand-picked candidate, Oscar K. Allen, had won the Democratic nomination for governor. Senator Long maintained his control over Louisiana state government until his death in 1935.

In Louisiana, Huey Long symbolized the rise to political power of lower-class whites. State government had been previously dominated by business interests and the New Orleans political machines. Going beyond mere symbolic gratification, Long pleased his followers by securing many material benefits, including free textbooks for all children in the public and private (religious) schools, construction of a network of free roads and bridges, increased expenditures for public education, and elimination of the poll tax, which was an effort by Southern Whites to block Blacks from voting.

Many Southern demagogues attacked the African Americans (who were not allowed to vote); this was called "playing the race card." Long never played that card, and made sure that blacks received a share of the benefits. At the same time, the level of taxation was increased markedly, much of the increase being borne by consumers directly through sales taxes. Long built a virtual personal dictatorship in Louisiana—the first (and last) in any American state—through the partisan administration of benefits, punitive actions against his opponents, and manipulation of the election laws. In 1934 he ordered state police to confront the New Orleans Democratic Party because Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley had a formidable opposition machine. Long drew back and no shots were fired. In 1934 he reorganized the legislature to put control in the hands of his allies. He transformed local government by giving the governor power to appoint local judges, election officials and tax assessors.

Despite not openly being a racial demagogue, Long nevertheless was a racist who opposed anti-lynching legislation. In an interview with Roy Wilkins when asked about the Costigan–Wagner Act and the Franklinton lynching, he said:[2]

You mean down in Washington parish? Oh, that? That one slipped up on us. Too bad, but those slips will happen. You know while I was governor there were no lynchings and since this man (Governor Allen) has been in he hasn't had any. (There have been 7 lynchings in Louisiana in the last two years.) This one slipped up. I can't do nothing about it. No sir. Can't do the dead n**** no good. Why, if I tried to go after those lynchers it might cause a hundred more n*****s to be killed. You wouldn't want that, would you?

Senator[edit]

Long challenged incumbent Senator Joseph Ransdell for Ransdell's seat in the United States Senate and won. However, his Senate term began in 1931, but his term as governor did not expire until May 1932. Long continued as governor until his hand chosen successor, O.K. Allen was elected.

While serving as Senator, Huey Long originally supported the New Deal program, but later he recanted his support for it. He wanted President Roosevelt to implement a "Share Our Wealth" program in which no American could have a personal fortune of more than $5,000,000, receive an income of greater than $1,000,000, or receive an inheritance of over $5,000,000. Any money earned after this would be divvied up and supposedly families would receive $2,000 to $2,500. His plan attracted significant support from the nation; it was estimated that he would get 10 percent the popular vote in the 1936 election against Franklin D. Roosevelt and Moderate Republican Alf Landon.

Senator Long broke with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in August 1933, conducted several spectacular filibusters against New Deal measures, and developed his own rival program --"Share Our Wealth"—by which poverty would be eliminated by confiscating the wealth of the rich and redistributing it equally to everyone. Long, relying on rapidly growing membership in his "Share Our Wealth" clubs and his large radio audience on NBC, was in position to run for the presidency in 1936 or 1940.[3]

Death[edit]

On Sept. 8, 1935, Long was shot and fatally wounded, presumably by Dr. Carl A. Weiss, Jr., in the state capitol at Baton Rouge. Long's bodyguards killed the assassin on the spot; Long himself died on September 10. Although Dr. Weiss was a member of a prominent anti-Long family, his motive probably was personal, not political; he believed that Long had sullied his family's honor.

Huey Long's book, My First Days in the White House, was published posthumously.

Legacy[edit]

Huey Long made important innovations in campaign technique, including sound trucks and radio commercials. His more lasting contribution was to the state of Louisiana rather than to the nation. He created a public works program unprecedented in the South, with a plethora of roads, bridges, hospitals, schools and state buildings. The Huey P. Long Bridge, located in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, is named in his honor.

He set in motion two durable factions within the dominant Louisiana Democratic party--"pro-Long" and "anti-Long," each diverging meaningfully in terms of policies and voter support. A family dynasty emerged: his brother Earl Long was elected lieutenant-governor in 1936, governor in 1948 and 1956. Typically anti-Longite candidates would promise to continue popular social services delivered in Long's administration and criticized Longite corruption without directly attacking Long himself. Huey's son Russell Long was a U.S. senator from 1948 to 1987. As chairman of the Senate Finance Committee, Russell Long shaped the nation's tax laws in a conservative fashion, with hardly any trace of his father's populism

Boisterous, scurrilous, and profane in speech; ruthless, violent, and unprincipled in action, the Kingfish was widely denounced in middle class circles and Democratic Party as a sinister ignoramus and buffoon. Dumb he was not; he showed disciplined intellectual performance of the highest order and was probably emotionally sincere in championing the cause of the underdog. His temperamental antagonism toward the socially privileged led to his ostentatious defiance of every propriety, knowing it was a sure-fire method of attracting the kind of alienated supporters he wanted.

He won in politics because of forcefulness and originality, and his perception that the governmental practices of Louisiana had become obsolete. He kept most of his promises and built roads, bridges, schools (including LSU) and other improvements which Louisiana needed. Flagrantly corrupt, he was primarily a coalition builder who used corruption to buy supporters. His improvement program was administered with relative efficiency. His success was in proportion to the weakness and confusion of his enemies, who were chiefly petty office-seekers, more decorous, but scarcely more ethical, than he. He was essentially a spokesman of a long-standing agrarian discontent that was much amplified and extended by the social and economic conditions of the great depression period.

Southern historian T. Harry Williams, the leading expert on Long, has a mixed evaluation that is mostly positive. Williams argues that Long stands without a rival as the greatest of Southern mass leaders. He asked the Southern United States to turn its gaze from "n*****" devils and take a long, hard look at itself. He asked people to forget the past, the glorious past and the sad past, and address themselves to the present. There is something wrong here, he said, and we can fix it up ourselves. Bluntly, forcibly, even crudely, he injected an element of realism into Southern politics. As Williams notes, not without reason did one of his unfavorable critics say that Long was the first Southerner since Calhoun to have an original idea, the first to extend the boundaries of political thought. Above all, Williams argues, he gave the Southern masses hope. He did some foolish things and some wrong things. There is a tragedy in the story, and perhaps it is not entirely his fault that he did not become the South's peerless Progressive. Perhaps the lesson of Long, says Williams, is that if in a democracy needed changes are denied too long by an interested minority, the changes, when they come, will come with a measure of repression and revenge. Perhaps the gravest indictment that can be made of Southern politics in recent times is that the urge for reform had to be accomplished by pressures that left in leaders like Long a degree of cynicism about the democratic process.[4]

Long in American literature[edit]

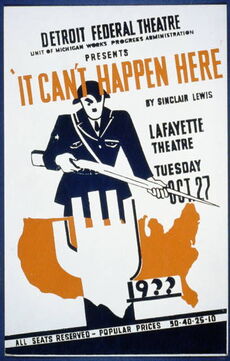

Political historians, and—especially—novelists have explored the strange dictatorship Long created. Long has been considered a demagogue by some, and at times referred to himself that way.[5][6] Sinclair Lewis's It Can’t Happen Here (1935), by a Nobel-Prize winning novelist, portrayed a genuine American dictator on the Hitler model.[7] Starting in 1936 the WPA, a New Deal agency, performed the theatre version across the country. Written with the express purpose of hurting Long's chances in the 1936 election, Lewis's novel outfits President Berzelius Windrip with a private militia, concentration camps, and a chief of staff who sounds like Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels. Lewis also outfits Windrip with a racist ideology completely alien to Long and a Main Street conservatism he also never embraced. Ultimately, Windrip is a venal and cynical showman who plays to the conformist resentments Lewis diagnosed in Main Street and Babbitt. Perry (2004) argues that the key weakness of the novel is not that he decks out American politicians with sinister European touches, but that he finally conceives of fascism and totalitarianism in terms of traditional American political models rather than seeing them as introducing a new kind of society and a new kind of regime. Windrip is less a Nazi than a con-man-plus-Rotarian, a manipulator who knows how to appeal to people's desperation, but neither he nor his followers are in the grip of the kind of world-transforming ideology like Hitler's National Socialism.

Hamilton Basso wrote two novels looking at Long, Cinnamon Seed (1934) and Sun in Capricorn (1942). Basso was a slashingly witty critic of the moonlight and magnolia romanticism of the Old South that dominated the Southern mind before 1920. Like many proponents of a New South, he wanted modernizers to take over. Cinnamon Seed's Harry Brand incorporates more details from the historical Huey Long than any other fictional portrayal does, and much of the novel is so lightly fictionalized that only a single letter separates the characters and places from their real-life counterparts.[8] Brand is a representative of the grasping and vulgar kind of new leadership which has rightly understood that the values of the Old South are played out but has replaced them with nothing but ambition and cunning. He is a greedy climber, not a demonic leader of the masses, and in fact he is ultimately not much more than an obnoxious and sticky-fingered lout, the kind who spits tobacco juice on the marble floors of his predecessors and pockets the ashtrays. In portraying his Long figure this way, Basso finds himself between the stools, critical of the spent aristocrats who cannot imagine a modern South, but disgusted also by the figures who represent the wrong kind of newness, the kind of modern South that comes to be if its development is left to default.[9]

John Dos Passos’s Number One (1943) looks not at the politics of mass brutality whipped up by manipulative demagogues, but at the gradual ebbing away of Long's idealist convictions under the pressure of a thousand expedient compromises and betrayals in the name of institutional necessity.[10]

Robert Penn Warren’s Pulitzer prize-winning All the King’s Men (1946) is the centerpiece of American political fiction. Warren’s spellbinding Willie Stark, almost as much philosopher as politician, bears the least resemblance to Long though for almost six decades Stark has been Long’s best-known fictional embodiment as a novel and well-received 1949 movie (it won three Oscars, including best picture and best actor as Broderick Crawford played the Long role.).[11]

The novelists portray Long's rise to power as a justifiable popular reaction against the selfish policies pursued by the dominant economic interests prior to 1928. They speculate the degree his extremism reflected an overreaction to his enemies, or sprang inevitably from class conflict in the state. They all try to explain why Long enjoyed majority support in Louisiana, both during and after his lifetime.

See also[edit]

- James Carville

- Hilda Phelps Hammond

- Earl Long

- Russell Long

- Speedy Long

- Gillis Long

- James A. Noe

- James Monroe Smith

Bibliography[edit]

- Bloom, Harold. Robert Penn Warren's All the King's Men (1987) online edition

- Boulard, Garry. Huey Long: His Life in Photos, Drawings, and Cartoons. Gretna, La.: Pelican, 2003. 127 pp.

- Boulard, Garry. Huey Long Invades New Orleans: The Siege of a City, 1934-36. Gretna, La.: Pelican, 1998. 277 pp.

- Brinkley, Alan. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, & the Great Depression (1982), 348pp ; argues Long was a Jeffersonian trying protect the traditionalistic yeoman farmer from the modernizing encroachments of the rich elites; excerpt and text search

- Burt, John. "Thirteen Ways of Kooking at a Kingfish." The Mississippi Quarterly 58#3-4 (2005) pp 795+. online edition

- Cortner, Richard C. The Kingfish and the Constitution: Huey Long, the First Amendment, and the Emergence of Modern Press Freedom in America. Greenwood, 1996. 196 pp. online edition

- Gunn, Joshua. "Hystericizing Huey: Emotional Appeals, Desire, and the Psychodynamics of Demagoguery." Western Journal of Communication 21#1 (2007) pp. 1+. online edition

- Haas, Edward F., ed. The Age of the Longs: Louisiana, 1928-1960. (Louisiana Purchase Bicentennial Series, vol. 8.) Lafayette, Louisiana: Center for Louisiana Studies, 2001. 527 pp.

- Hair, William Ivy. The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long (1991) 406pp, standard scholarly biography; less favorable than Williams

- Howard, Perry H. Political Tendencies in Louisiana (1971), by political scientist online edition

- Jeansonne, Glen. Messiah of the Masses: Huey P. Long and the Great Depression. 1993. 204 pp. short, scholarly and very hostile

- Jeansonne, Glen, ed. Huey at 100: Centennial Essays on Huey P. Long. Ruston, La.: McGinty, 1995. 237 pp.

- Kane, Harnett T. Louisiana Hayride: The American Rehearsal for Dictatorship, 1928-1940 (1949) 476 pp. journalistic and sensational (Williams is better) online edition

- Perry, Keith Ronald. The Kingfish in Fiction: Huey P. Long and the Modern American Novel (2004) 224pp excerpt and text search

- Potter, David M. "Long, Huey Pierce, (Aug. 30, 1893 - Sept. 10, 1935),' Dictionary of American Biography Supp 1 (1964)

- Sanson, Jerry P., "'What he did and what he promised to do': Huey Long and the Horizons of Louisiana Politics," Louisiana History, 47 (Summer 2006), 261–76.

- Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr., The Age of Roosevelt, vol 3: The Politics of Upheaval (1960), chapter on Long

- Sindler, Alan P. Huey Long's Louisiana: State Politics 1928-1940 (1956) by political scientist

- Steinberg, Alfred. The Bosses: Frank Hague, James Curley, Ed Crump, Huey Long, Gene Talmadge, Tom Pendergast - The Story of the Ruthless Men who Forged the American Political Machines that Dominated the Twenties and Thirties. 1972. 379 pp.

- Williams, T. Harry. "The Gentleman from Louisiana: Demagogue or Democrat." The Journal of Southern History 26 (1960): 3-21. in JSTOR

- Williams, T. Harry. Huey Long (1969); 949pp; Pulitzer Prize; the standard scholarly biography; generally favorable excerpt and text search

- PBS, Ken Burns's 1987 documentary

Primary sources[edit]

- Long, Huey P. Kingfish to America: Share Our Wealth. edited by Henry M. Christman; (1985). 143 pp.

notes[edit]

- ↑ Although the Klan is best known for its actions against blacks, they also have a long hatred of Catholics as many of their members claim membership in non-mainline Protestant churches. Louisiana was -- and still is -- religiously divided between the predominantly Protestant north and the predominantly Catholic south.

- ↑ Costigan-Wagner Act. Spartacus Educational. Retrieved April 21, 2021.

- ↑ The Rev. Gerald L. K. Smith (1898-1976) was Long's national organizer; in the late 1930s Smith became a prominent enemy of Jews, but he was not openly anti-Semitic during his time with Long. Glen Jeansonne, "Gerald L. K. Smith: from Wisconsin Roots to National Notoriety." Wisconsin Magazine of History 2002-03 86(2): 18-29. Issn: 0043-6534 Fulltext online

- ↑ T. Harry Williams, "The Gentleman from Louisiana: Demagogue or Democrat." Journal of Southern History 1960 26(1): 3-21.

- ↑ Plain Folk of the South Revisited

- ↑ The Kingfish and His Realm: The Life and Times of Huey P. Long

- ↑ See the full text at

- ↑ For example Basso uses "Tillson" instead of "Wilson", "Janders" rather than "Sanders", "Gwinn Parish" for "Winn Parish".

- ↑ Perry (2004)

- ↑ Perry (2004)

- ↑ Perry (2004); Bloom (1987)