| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Alone: Lutenyl With E2: Naemis, Zoely |

| Other names | NOMAC; NOMAc; Nomegesterol acetate; TX-066; TX-525; ORG-10486-0; Uniplant; 19-Normegestrol acetate; 6-Methyl-17α-acetoxy-δ6-19-norprogesterone; 17α-Acetoxy-6-methyl-19-norpregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1] |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Progestin; Progestogen ester; Steroidal antiandrogen |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 63%[1] |

| Protein binding | 97.5–98.0% (to albumin)[1] |

| Metabolism | Liver (by hydroxylation via CYP3A3, CYP3A4, CYP2A6)[1] |

| Metabolites | Six main metabolites, all essentially inactive[1] |

| Elimination half-life | ~50 hours (range 30–80 hours)[1][2] |

| Excretion | Urine, feces[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.055.781 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C23H30O4 |

| Molar mass | 370.489 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Nomegestrol acetate (NOMAC), sold under the brand names Lutenyl and Zoely among others, is a progestin medication which is used in birth control pills, menopausal hormone therapy, and for the treatment of gynecological disorders.[3][1][4][5][6][7] It is available both alone and in combination with an estrogen.[8][9] NOMAC is taken by mouth.[3] A birth control implant for placement under the skin was also developed but ultimately was not marketed.[10][11][12][13]

Side effects of NOMAC include menstrual irregularities, headaches, nausea, breast tenderness, and others.[1][14] NOMAC is a progestin, or a synthetic progestogen, and hence is an agonist of the progesterone receptor, the biological target of progestogens like progesterone.[3] It has some antiandrogenic activity and no other important hormonal activity.[3]

Nomegestrol, a related compound, was patented in 1975, and NOMAC was described in 1983.[15][16] NOMAC was first introduced for medical use, for the treatment of gynecological disorders and in menopausal hormone therapy, in Europe in 1986.[1][17][18] It was subsequently approved in Europe in 2011 as a component of birth control pills.[1][17][18] NOMAC is available widely throughout the world.[8][19] It is not available in the United States or Canada.[8][1][17][18]

Medical uses[edit]

NOMAC is used alone in the treatment of gynecological disorders including menstrual disturbances (e.g., dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, oligomenorrhea, polymenorrhea, amenorrhea), vaginal bleeding, breast pain, and premenstrual syndrome and in menopausal hormone therapy.[1][5][14] It is used in combination with estradiol as a birth control pill and in menopausal hormone therapy.[1][17][18] NOMAC-only tablets are also used as a form of progestogen-only birth control, although they are not specifically licensed as such.[20]

Available forms[edit]

NOMAC is available both alone and in combination with estrogens.[8][9] The following formulations are available:[8][9]

- NOMAC 3.75 mg and 5 mg oral tablets (Lutenyl) – indicated for menopausal hormone therapy and gynecological disorders

- NOMAC 3.75 mg and estradiol 1.5 mg oral tablets (Naemis) – indicated for menopausal hormone therapy

- NOMAC 2.5 mg and estradiol 1.5 mg oral tablets (Zoely) – indicated for birth control

The availability of these formulations differs by country.[8]

Contraindications[edit]

Because NOMAC is metabolized by the liver, hepatic impairment can result in an accumulation of the medication.[21]

Side effects[edit]

The side effects of NOMAC are similar to those of other progestogens.[1] It is well tolerated and often produces no side effects.[1] Possible side effects of NOMAC include menstrual irregularities (e.g., abnormal bleeding or spotting), headache, nausea, breast tenderness, and weight gain.[1][17][22][23][14] However, body weight is generally unchanged.[1] Rarely, meningiomas have been reported in association with NOMAC.[24][25][26][27]

Overdose[edit]

There have been no reports of serious adverse effects due to overdose of NOMAC.[7] NOMAC has been administered alone at a dosage of up to 40 times the recommended dosage, and the combination of NOMAC and estradiol has been administered in multiple doses of up to 5 times the recommended dosage to women in clinical trials, and no safety concerns or harmful effects were observed in either case.[28][7] Symptoms of NOMAC and estradiol overdose might include nausea, vomiting, and, in young girls, slight vaginal bleeding.[7] There is no antidote for NOMAC overdose and treatment of overdose should be based on symptoms.[7]

Interactions[edit]

The metabolism of NOMAC is dependent on CYP3A4, so inhibitors and inducers of this enzyme such as ketoconazole and rifampicin, respectively, as well as some anticonvulsants, may pose a clinically significant drug interaction with NOMAC.[1][2] (For a list of CYP3A4 inhibitors and inducers, see here.)

Pharmacology[edit]

Pharmacodynamics[edit]

NOMAC has progestogenic activity, antigonadotropic effects, antiandrogenic activity, and no other important hormonal activity.[3]

| Compound | PR | AR | ER | GR | MR | SHBG | CBG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nomegestrol acetate | 125 | 42 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Megestrol acetate | 65 | 5 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Progesterone | 50 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 100 | 0 | 36 | |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were promegestone for the PR, metribolone for the AR, estradiol for the ER, dexamethasone for the GR, aldosterone for the MR, dihydrotestosterone for SHBG, and cortisol for CBG. Sources: [3] | ||||||||

Progestogenic activity[edit]

NOMAC is a potent and pure progestogen, acting as a selective, high-affinity full agonist of the progesterone receptor (PR) (Ki = 3 nM, 67–303% of the relative binding affinity of progesterone),[29] and is said to have higher potency and substantially improved selectivity for the PR relative to medroxyprogesterone acetate (the 6-hydrogenated or non-6-7-double bonded analogue of megestrol acetate and the most widely used progestin).[4][30][31] In accordance, NOMAC is a potent antigonadotropin and exhibits no androgenic, estrogenic,[32] glucocorticoid, or antimineralocorticoid activity,[1] but does possess some antiandrogenic activity.[29][33] Due to its potent antigonadotropic activity, NOMAC has strong functional antiandrogenic and antiestrogenic effects when administered at sufficiently high doses.[1]

Like many other progestogens,[34][35] NOMAC has been assessed and found in vitro to inhibit the conversion of estrone sulfate to estrone (via inhibition of steroid sulfatase) and estrone to estradiol (via inhibition of 17β-HSD) at high concentrations (0.5–50 μM) and to stimulate the conversion of estrone into estrone sulfate (via activation of estrogen sulfotransferase activity) at low concentrations (0.05–0.5 μM), whilst not affecting aromatase activity at any tested concentration (up to 10 μM).[1][5] These activities appear to be PR-dependent, as NOMAC is more potent in producing them in PR-rich cell lines (e.g., T47-D vs. MCF-7) and they can be blocked by the PR antagonist mifepristone (RU-486).[5] Although the clinical implications of these actions are unclear and they have yet to be confirmed in vivo or assessed in clinical studies, it has been suggested that NOMAC and certain other progestins may be useful in the treatment of ER-positive breast cancer by decreasing levels of estrogens in breast tissue.[34][35] In accordance with this notion, in vitro, NOMAC does not have proliferative effects on breast tissue, does not stimulate breast cell proliferation via PGRMC1 (similarly to progesterone), and reduces the breast proliferative effects of estradiol when added to it in medium.[36]

Antigonadotropic effects[edit]

The ovulation-inhibiting dosage of NOMAC is 1.5 to 5 mg/day.[1][3][37] Due to its high antigonadotropic activity and its long elimination half-life, the contraceptive effectiveness of NOMAC is maintained even when a dose is missed; clinical studies found no increased incidence of pregnancy with one missed pill of Zoely or even with two missed pills during days 8 to 17 of the menstrual cycle.[2]

Antiandrogenic activity[edit]

NOMAC acts as an antagonist of the androgen receptor (AR), with approximately 12 to 31% of the relative binding affinity of testosterone for the AR and 42% of the affinity of metribolone for the AR.[4][31][38][3] Estimates of the antiandrogenic potency of NOMAC are mixed, ranging from 5 to 20%, 20 to 30%, and 90% of that of cyproterone acetate depending on the source.[29][33][3][39][40][41] The antiandrogenic activity of NOMAC may be useful in helping to alleviate acne, seborrhea, and other androgen-dependent symptoms in women.[2][41]

Other activity[edit]

Certain progestins have been found to stimulate the proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells in vitro, an action that is independent of the classical PRs and is instead mediated via the progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (PGRMC1).[42] Progesterone and NOMAC, in contrast, act neutrally in this assay.[42] It is unclear if these findings may explain the different risks of breast cancer observed with progesterone and progestins in clinical studies.[43]

Pharmacokinetics[edit]

NOMAC is well-absorbed, with an oral bioavailability of 63%.[1] It is 97.5 to 98% protein-bound, to albumin, and does not bind to sex hormone-binding globulin or corticosteroid-binding globulin.[1] The medication is metabolized hepatically via hydroxylation by the enzymes CYP3A3, CYP3A4, and CYP2A6.[1] It has six main metabolites, all of which have no or minimal progestogenic activity.[1] The elimination half-life of NOMAC is approximately 50 hours, with a range of 30 to 80 hours.[1][2] Steady-state concentrations of NOMAC are achieved after five days of repeated administration.[1] As Zoely (2.5 mg/day NOMAC), the average circulating concentrations of NOMAC are 4.5 ng/mL at steady-state, with minimum and maximum concentrations of 3.1 ng/mL and 12.3 ng/mL, respectively.[2] The medication is eliminated via urine and feces.[1]

Chemistry[edit]

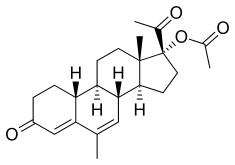

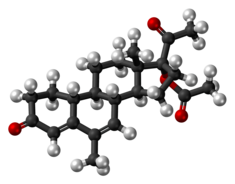

NOMAC, also known as 17α-acetoxy-6-methyl-δ6-19-norprogesterone or as 17α-acetoxy-6-methyl-19-norpregna-4,6-diene-3,20-dione, is a synthetic norpregnane steroid and a derivative of progesterone belonging to the 19-norprogesterone and 17α-hydroxyprogesterone groups.[15] NOMAC is the C17α acetate ester of nomegestrol and the 19-demethylated (or 19-nor) analogue of megestrol acetate, and can also be referred to as 19-normegestrol acetate.[15][4]

History[edit]

Nomegestrol was patented in 1975, and NOMAC, under the developmental code name TX-066, was first described in the literature in 1983.[15][16] It was developed by Theramex Laboratories, a pharmaceutical company in Monaco (a satellite country of France).[1] The medication was first introduced in Europe alone or in combination with estradiol under the respective brand names Lutenyl and Naemis[5] for the treatment of gynecological disorders and menopausal symptoms in 1986, and was subsequently developed and approved in 2011 in Europe as a birth control pill in combination with estradiol under the brand name Zoely.[1][17][18] As Zoely, NOMAC has been studied in over 4,000 women as a method of birth control.[2]

Society and culture[edit]

Generic names[edit]

Nomegestrol acetate is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, and BAN.[15][19][8] It is also known by its former developmental code name TX-066.[15][19][8]

Brand names[edit]

NOMAC is marketed in combination with estradiol as a birth control pill primarily under the brand name Zoely, in combination with estradiol for use in menopausal hormone therapy primarily under the brand name Naemis, and as a standalone medication for use in menopausal hormone therapy and the treatment of gynecological disorders primarily under the brand name Lutenyl.[8] NOMAC is also marketed alone or in combination with estradiol under a variety of other less common brand names throughout the world.[8]

Availability[edit]

NOMAC (either alone (e.g., as Lutenyl) or in combination with estradiol (e.g., as Naemis))[5] is available for the treatment of gynecological disorders and menopausal symptoms in Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Chile, France,[44][45] Georgia, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Italy, Lebanon, Lithuania, Malta, Monaco, the Netherlands, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Taiwan, Tunisia, Turkey, and Vietnam.[8][46][47][19] As a component of birth control pills with estradiol (under the brand name Zoely), NOMAC is available in Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Chile, Colombia, Croatia, Costa Rica, Denmark, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Finland, France, Germany, Guatemala, Honduras, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Malaysia, Monaco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Poland, Portugal, Russia, Spain, Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.[8][46][47][19] It was expected that Zoely would become available in the United States in 2010,[48] but the FDA rejected the NDA for Zoely in 2011[49] and NOMAC ultimately has not been introduced in any form in this country.[50]

Research[edit]

Under the tentative brand name Uniplant, NOMAC was under development by Theramex as a 38 mg or 55 mg 4 cm Silastic (silicone-plastic) subcutaneous birth control implant of one-year duration (75 ug/day or 100 μg/day release rate) in Brazil from the 1990s and was extensively studied for this purpose in clinical trials.[10][11][12][13] The clinical studies included 19,900 women-months of use and demonstrated a one-year failure rate of 0.94%. Uniplant was regarded as showing high effectiveness, and was well tolerated.[13] In spite of this however, "[f]urther plans to make it available have been deferred by decision of the company holding the progestin patent",[51] and, although it continued to be investigated as late as 2006,[52] the implant ultimately never became commercially available.[53][54]

Oral NOMAC was under development for the treatment of breast cancer and for use as a progestogen-only pill for birth control but did not complete development for these indications.[55] An estradiol and NOMAC vaginal ring was under development for use in birth control and to treat dysmenorrhea but did not complete development and was not marketed.[56] A continuous oral formulation of estradiol and NOMAC was under development for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and the treatment or prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis but did not complete development.[57]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af Lello, Stefano (2010). "Nomegestrol Acetate". Drugs. 70 (5): 541–559. doi:10.2165/11532130-000000000-00000. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 20329803. S2CID 24780717.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ruan, Xiangyan; Seeger, Harald; Mueck, Alfred O. (2012). "The pharmacology of nomegestrol acetate". Maturitas. 71 (4): 345–353. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.01.007. ISSN 0378-5122. PMID 22364709.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. S2CID 24616324.

- ^ a b c d Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1403–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Shields-Botella, J.; Chetrite, G.; Meschi, S.; Pasqualini, J.R. (2005). "Effect of nomegestrol acetate on estrogen biosynthesis and transformation in MCF-7 and T47-D breast cancer cells". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 93 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.11.004. ISSN 0960-0760. PMID 15748827. S2CID 25273633.

- ^ http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002068/WC500120841.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c d e https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/auspar-zoely.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Zoely: Uses, Side Effects, Benefits/Risks".

- ^ a b c http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/001213/WC500115833.pdf[bare URL PDF]

- ^ a b Brache, V.; Faundes, A.; Alvarez, F.; Cochon, L. (2002). "Nonmenstrual adverse events during use of implantable contraceptives for women: data from clinical trials". Contraception. 65 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00289-X. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 11861056.

- ^ a b Erkkola, Risto; Landgren, Britt-Marie (2005). "Role of progestins in contraception". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 84 (3): 207–216. doi:10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00759.x. ISSN 0001-6349. PMID 15715527. S2CID 6887415.

- ^ a b Donna Shoupe (10 February 2011). Contraception. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-1-4443-4263-5.

- ^ a b c Royer, Pamela A.; Jones, Kirtly P. (2014). "Progestins for Contraception". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 57 (4): 644–658. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000072. ISSN 0009-9201. PMID 25314087.

- ^ a b c "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-01-09. Retrieved 2018-01-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d e f J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. p. 883. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- ^ a b Paris J, Thévenot R, Bonnet P, Granero M (1983). "The pharmacological profile of TX 066 (17 alpha-acetoxy-6-methyl-19-nor-4,6-pregna-diene-3,20-dione), a new oral progestative". Arzneimittelforschung. 33 (5): 710–5. PMID 6683550.

- ^ a b c d e f Yang, Lily P.H.; Plosker, Greg L. (2012). "Nomegestrol Acetate/Estradiol". Drugs. 72 (14): 1917–1928. doi:10.2165/11208180-000000000-00000. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 22950535. S2CID 44335732.

- ^ a b c d e Burke, Anne (2013). "Nomegestrol acetate-17b-estradiol for oral contraception". Patient Preference and Adherence. 7: 607–19. doi:10.2147/PPA.S39371. ISSN 1177-889X. PMC 3702550. PMID 23836965.

- ^ a b c d e Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 747–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ Gourdy P, Bachelot A, Catteau-Jonard S, Chabbert-Buffet N, Christin-Maître S, Conard J, Fredenrich A, Gompel A, Lamiche-Lorenzini F, Moreau C, Plu-Bureau G, Vambergue A, Vergès B, Kerlan V (November 2012). "Hormonal contraception in women at risk of vascular and metabolic disorders: guidelines of the French Society of Endocrinology". Ann. Endocrinol. (Paris). 73 (5): 469–87. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2012.09.001. PMID 23078975.

- ^ Bińkowska M, Woroń J (2015). "Progestogens in menopausal hormone therapy". Prz Menopauzalny. 14 (2): 134–43. doi:10.5114/pm.2015.52154. PMC 4498031. PMID 26327902.

- ^ Rowlands S (2003). "Newer progestogens". J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 29 (1): 13–6. doi:10.1783/147118903101197188. PMID 12626173.

- ^ Lyseng-Williamson, Katherine A.; Yang, Lily P. H.; Plosker, Greg L. (2012). "Nomegestrol acetate/estradiol: a guide to its use in oral contraception". Drugs & Therapy Perspectives. 29 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1007/s40267-012-0005-9. ISSN 1172-0360. S2CID 71591520.

- ^ Passeri T, Champagne PO, Bernat AL, Hanakita S, Salle H, Mandonnet E, Froelich S (April 2019). "Spontaneous regression of meningiomas after interruption of nomegestrol acetate: a series of three patients". Acta Neurochir (Wien). 161 (4): 761–765. doi:10.1007/s00701-019-03848-x. PMID 30783806. S2CID 67750259.

- ^ Champagne PO, Passeri T, Froelich S (March 2019). "Combined hormonal influence of cyproterone acetate and nomegestrol acetate on meningioma: a case report". Acta Neurochir (Wien). 161 (3): 589–592. doi:10.1007/s00701-018-03782-4. PMID 30666456. S2CID 58573065.

- ^ Amelot A, van Effenterre R, Kalamarides M, Cornu P, Boch AL (March 2018). "Natural history of cavernous sinus meningiomas". J. Neurosurg. 130 (2): 435–442. doi:10.3171/2017.7.JNS17662. PMID 29600913.

- ^ "Actualité - Luteran (Acétate de chlormadinone) et Lutényl (Acétate de nomégestrol) et leurs génériques : Des cas de méningiome rapportés - ANSM".

- ^ http://mri.cts-mrp.eu/download/BE_H_0137_001_FinalSPC.pdf[dead link]

- ^ a b c Mueck, Alfred O.; Sitruk-Ware, Regine (2011). "Nomegestrol acetate, a novel progestogen for oral contraception". Steroids. 76 (6): 531–539. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2011.02.002. ISSN 0039-128X. PMID 21335021. S2CID 27419175.

- ^ Irwin Goldstein; Cindy M. Meston; Susan Davis; Abdulmaged Traish (17 November 2005). Women's Sexual Function and Dysfunction: Study, Diagnosis and Treatment. CRC Press. pp. 554–. ISBN 978-1-84214-263-9.

- ^ a b Hapgood, J.P.; Africander, D.; Louw, R.; Ray, R.M.; Rohwer, J.M. (2014). "Potency of progestogens used in hormonal therapy: Toward understanding differential actions". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 142: 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.08.001. ISSN 0960-0760. PMID 23954501. S2CID 12142015.

- ^ Jorge R. Pasqualini (17 July 2002). Breast Cancer: Prognosis, Treatment, and Prevention. CRC Press. pp. 224–. ISBN 978-0-203-90924-9.

- ^ a b Sitruk-Ware R (2002). "Progestogens in hormonal replacement therapy: new molecules, risks, and benefits". Menopause. 9 (1): 6–15. doi:10.1097/00042192-200201000-00003. PMID 11791081. S2CID 12136231.

- ^ a b Pasqualini, Jorge R. (2009). "Progestins and breast cancer". Gynecological Endocrinology. 23 (sup1): 32–41. doi:10.1080/09513590701585003. ISSN 0951-3590. PMID 17943537. S2CID 46634314.

- ^ a b Pasqualini, Jorge R. (2009). "Breast cancer and steroid metabolizing enzymes: The role of progestogens". Maturitas. 65: S17–S21. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.006. ISSN 0378-5122. PMID 19962254.

- ^ Del Pup, Lino; Berretta, Massimiliano; Di Francia, Raffaele; Cavaliere, Carla; Di Napoli, Marilena; Facchini, Gaetano; Fiorica, Francesco; Mileto, Mario; Schindler, Adolf E. (2014). "Nomegestrol acetate/estradiol hormonal oral contraceptive and breast cancer risk". Anti-Cancer Drugs. 25 (7): 745–750. doi:10.1097/CAD.0000000000000050. ISSN 0959-4973. PMID 24346139. S2CID 33806950.

- ^ Kuhl H (2011). "Pharmacology of Progestogens" (PDF). J Reproduktionsmed Endokrinol. 8 (1): 157–177.

- ^ A.R. Genazzani (15 May 2001). Hormone Replacement Therapy and Cardiovascular Disease: The Current Status of Research and Practice. CRC Press. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-1-84214-038-3.

- ^ Wiegratz I, Kuhl H (2006). "Metabolic and clinical effects of progestogens". Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 11 (3): 153–61. doi:10.1080/13625180600772741. PMID 17056444. S2CID 27088428.

- ^ Sitruk-Ware R, Husmann F, Thijssen JH, Skouby SO, Fruzzetti F, Hanker J, Huber J, Druckmann R (September 2004). "Role of progestins with partial antiandrogenic effects". Climacteric. 7 (3): 238–54. doi:10.1080/13697130400001307. PMID 15669548. S2CID 23112620.

- ^ a b Kuhl, Herbert (1996). "Comparative Pharmacology of Newer Progestogens". Drugs. 51 (2): 188–215. doi:10.2165/00003495-199651020-00002. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 8808163. S2CID 1019532.

- ^ a b Neubauer H, Ma Q, Zhou J, Yu Q, Ruan X, Seeger H, Fehm T, Mueck AO (October 2013). "Possible role of PGRMC1 in breast cancer development". Climacteric. 16 (5): 509–13. doi:10.3109/13697137.2013.800038. PMID 23758160. S2CID 29808177.

- ^ Trabert B, Sherman ME, Kannan N, Stanczyk FZ (September 2019). "Progesterone and breast cancer". Endocr. Rev. 41 (2): 320–344. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnz001. PMC 7156851. PMID 31512725.

- ^ Löwy, Ilana; Weisz, George (2005). "French hormones: progestins and therapeutic variation in France". Social Science & Medicine. 60 (11): 2609–2622. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.021. ISSN 0277-9536. PMID 15814185.

- ^ Foidart, Jean-Michel; Beliard, Aude; Hedon, Bernard; Ochsenbein, Edith; Bernard, Anne-Marie; Bergeron, Christine; Thomas, Jean-Louis (1997). "Impact of percutaneous oestradiol gels in postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy on clinical symptoms and endometrium". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 104 (3): 305–310. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb11458.x. ISSN 1470-0328. PMID 9091006. S2CID 28718791.

- ^ a b http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Sweetman, Sean C., ed. (2009). "Sex hormones and their modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. p. 2119. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1.

- ^ Gretchen M Lentz; Rogerio A. Lobo; David M Gershenson; Vern L. Katz (21 February 2012). Comprehensive Gynecology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-0-323-09131-2.

- ^ "FDA Turns Down Merck Birth Control Pill, Glaucoma Drug". 10 November 2011.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ Croxatto, H (2000). "Progestin implants". Steroids. 65 (10–11): 681–685. doi:10.1016/S0039-128X(00)00124-0. ISSN 0039-128X. PMID 11108876. S2CID 42296395.

- ^ Barbosa, Ione Cristina; Maia, Hugo; Coutinho, Elsimar; Lopes, Renata; Lopes, Antonio C.V.; Noronha, Cristina; Botto, Adelmo (2006). "Effects of a single Silastic® contraceptive implant containing nomegestrol acetate (Uniplant) on endometrial morphology and ovarian function for 1 year" (PDF). Contraception. 74 (6): 492–497. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.013. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 17157108.

- ^ Croxatt, Horacio B. (2002). "Progestin implants for female contraception". Contraception. 65 (1): 15–19. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(01)00293-1. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 11861051.

- ^ McDonald-Mosley, Raegan; Burke, Anne (2010). "Contraceptive Implants". Seminars in Reproductive Medicine. 28 (2): 110–117. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1248135. ISSN 1526-8004. PMID 20352560.

- ^ "Nomegestrol oral - AdisInsight".

- ^ "Estradiol/Nomegestrol intravaginal ring - AdisInsight".

- ^ "Estradiol/Nomegestrol continuous - AdisInsight".

Further reading[edit]

- Lello, Stefano (2010). "Nomegestrol Acetate: Pharmacology, Safety Profile and Therapeutic efficacy". Drugs. 70 (5): 541–559. doi:10.2165/11532130-000000000-00000. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 20329803. S2CID 24780717.

- Mueck, Alfred O.; Sitruk-Ware, Regine (2011). "Nomegestrol Acetate, a Novel Progestogen for Oral Contraception". Steroids. 76 (6): 531–539. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2011.02.002. ISSN 0039-128X. PMID 21335021. S2CID 27419175.

- Ruan, Xiangyan; Seeger, Harald; Mueck, Alfred O. (2012). "The pharmacology of nomegestrol acetate". Maturitas. 71 (4): 345–353. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.01.007. ISSN 0378-5122. PMID 22364709.

- van Diepen, Harry A (2012). "Preclinical pharmacological profile of nomegestrol acetate, a synthetic 19-nor-progesterone derivative". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 10 (1): 85. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-10-85. ISSN 1477-7827. PMC 3571880. PMID 23043680.

- Yang, Lily P.H.; Plosker, Greg L. (2012). "Nomegestrol Acetate/Estradiol". Drugs. 72 (14): 1917–1928. doi:10.2165/11208180-000000000-00000. ISSN 0012-6667. PMID 22950535. S2CID 44335732.

- Burke, Anne (2013). "Nomegestrol acetate-17b-estradiol for oral contraception". Patient Preference and Adherence. 7: 607–19. doi:10.2147/PPA.S39371. ISSN 1177-889X. PMC 3702550. PMID 23836965.