| Christ died for our articles about Christianity |

| Schismatics |

| Devil's in the details |

The Divine Comedy (not to be confused with the other one) is an Italian epic poem written by Dante Alighieri over the course of 12 years (1308-1320 CE). It deeply affected the medieval worldview of the afterlife, effects which can still be seen today. The poem details Dante being escorted through Hell and Purgatory by the Roman poet Virgil, and through paradise by an old love, Beatrice, after being lost in the dark forest of sin. It has been said that it represents allegorically the soul's journey towards God.

Despite being a religious poem, which discusses sin, virtue, and theology, Dante also discusses several elements of the science of his day, especially physics and astronomy. He discusses the importance of the scientific method and the implications of a spherical Earth, despite adopting a Ptolemaic cosmological system.[1] Many scientists and philosophers from Galileo to Newton have been influenced by the work.

The Divine Comedy was not meant to be taken literally; it was intended as an allegory; each canto contains many alternative meanings. Dante's allegory, however, is more complex, and, in explaining ways to interpret the poem – see the Letter to Cangrande[2] – he outlines other levels of meaning besides the allegory: the historical, the moral, the political, and the philosophical.

Dante's poem has also been controversial due to the fact that many greedy popes and cardinals are sent to Hell in the Inferno for their crimes of simony.![]() Among these figures include Pope Nicholas III, Pope Boniface VIII, and Pope Clement V.[3] Dante also sends Pope Celestine V into the vestibule of Hell in the Inferno, whose "cowardice" served as the door through which so much evil entered the Church".[4] Dante criticises the greedy corruption of the Church and many of its leaders.

Among these figures include Pope Nicholas III, Pope Boniface VIII, and Pope Clement V.[3] Dante also sends Pope Celestine V into the vestibule of Hell in the Inferno, whose "cowardice" served as the door through which so much evil entered the Church".[4] Dante criticises the greedy corruption of the Church and many of its leaders.

Dante also supported the separation of church and state; which was progressive for a man born in 1265. Dante outlines his idea in De Monarchia (the work is in Latin). The treatise was so controversial it was banned by the Catholic Church. [5]

Introduction[edit]

The poem starts on the Thursday before Good Friday with Dante becoming lost in a dark forest often seen as a representation of sin in comparison to the straight way. Dante states he is halfway through the journey of life; Biblically, this is supposed to be 70, so the readers can infer he is 35 at the time.[6] After getting lost, Dante attempts to climb a mountain to find his way but is chased by a leopard, lion, and she-wolf. These represent allegories as well:

- The lion — Violence and bestial nature

- The leopard — Fraud and malice

- The she-wolf — Incontinence: It meant lack of self-control at the time.

Dante is then chased into a cave where he meets Virgil and the story rightly begins.

The Inferno[edit]

The most well-known part of Dante's epic poem due to its intense and imaginative imagery. There are 9 circles of hell, often grouped into three perversions of love.[7] Violence is split to an additional 3 and fraud has an additional 10. Dante obviously had a very special place in hell for fraud. Interestingly, Dante often includes Roman mythological creatures, contemporary Italian figures (several of which Dante had met himself), and Biblical figures throughout Hell.

- The Vestibule of Hell: The place for those who were indecisive and opportunistic, refusing to take a side for either good or evil; though undeserving of Heaven they are not wicked enough for Hell proper. As they would not take a stand on anything, they are forced to chase a constantly moving banner (representing their own self-interest) while being pursued by wasps and hornets that sting them.

- Deficient Love

- First Circle: Limbo, or the abyss. The place for the unbaptized and virtuous pagans, for those who could not choose God but choose human virtue.[8] It is abode of famous Roman figures, Greek figures and Greek mythological heroes who had the misfortunate of being born in the wrong time period. The Muslim general Saladin is there for having shown mercy in combat. It formerly housed some righteous Jews from the Old Testament, like Noah and Moses, who were born before the New Testament, but, after his crucifixion, Jesus descended into Limbo and took them into Heaven in an event known as the Harrowing of Hell.

- Dante stated Without baptism they lacked the hope for something greater than rational minds can conceive.[9] An odd comment, given that Limbo is home to good reasonable people who couldn't have been baptized and the next circle is the abode of the baptized who let desire overwhelm their reason.

- Excessive Love — The circles of Incontinence

- Second Circle: Lust — Where hell properly begins. It is called a part where no thing gleams.[10] Here the serpent Minos judges souls and assigns them to the corresponding by winding itself around their bodies. The sinners that let their appetites overwhelm their reason[11] are condemned to be constantly buffeted by raging storms in this circle, much as their lusts carried them from one passion to another. As it nevertheless requires an element of mutuality and is thus not entirely self-centered, Dante views lust as the least heinous of the sins. Figures in this circle include Dido, Cleopatra, Semiramis, Helen of Troy, and Paris. A segment is dedicated to the story of Francesca da Rimini, whose adulterous affair with her husband's brother Paolo ended with them both being murdered by her husband.

- Third Circle: Gluttony — The mutual self-indulgence of the lustful devolves into the solitary self-indulgence of the gluttonous. The gluttons wallow in a vile, disgusting slush produced by a ceaseless, foul, icy rain in nearly pure putrefaction, grating against every one of the senses that they indulged in life. Cerberus dwells here as well, gnawing upon the sinners. Here Dante meets a contemporary called "Ciacco" (literally "the hog") who speaks to him of the current strife in Dante's native Florence and the impending expulsion of Dante's party from the city (while it had already happened at the time of writing, the poem is set two years beforehand). [12]

- Fourth Circle: Greed — Pluto, otherwise known as Hades, guards the realm of those whose attitude towards material goods was outside the appropriate mean.[13] In the Inferno, this generally gets explained as to hoard or to squander wealth. In hell the hoarders and squanderers alike joust with weapons of great weights, often depicted as bags of money in art. Their mutual antagonism blinds them to the truth that they are guilty of the same sin.

- Malicious Love

- Fifth Circle: Wrath — Located on the filthy stinking shore of the river Styx. The actively wrathful fight about the shore. Dante explains that there is also a group of the sullen (the passively wrathful) that lie directly beneath the water and are "sunk into a black sulkiness which can find no joy in God or man or the universe."[14] No antidepressants back in Dante's time so you get sent to hell instead.

- Sixth Circle: Heresy — Beyond the City of Dis, heretics get sealed in burning tombs: they denied the immortality of the soul, and so they are entombed in Hell. Most notable here are the followers of Epicurus and Farinata degli Uberti, a powerful political leader condemned for heresy after his death. [15]

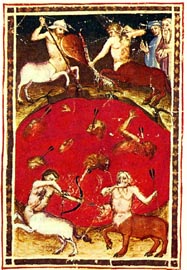

- Seventh Circle: Violence

- The Minotaur guards the exterior of the circle, representing the bestial nature of the sin of violence.

- Ring 1: Against neighbors — Here murderers, war-makers, plunderers and tyrants will be immersed in the Phlegethon, a burning river of boiling blood.[16] This river is patrolled by centaur sentries that shoot arrows into any sinner that attempts to escape. Among their number are warmongers and tyrants such as Attila the Hun and Alexander the Great.

- Ring 2: Against self — Suicides are turned into thorny trees that are fed upon by harpies. They are only allowed to speak when damaged.

- Ring 3: Against God, art, and nature — Here blasphemers, sodomites, and usurers are tortured in different fashions by the plain of burning sand burned by flakes of fire falling from the sky. Blasphemers are tied directly to the sand, sodomites are forced to run in circles, and usurers weep huddled on the sand. Included in their number are the king Capaneus (one of the Seven Against Thebes, who declared that Zeus would not stop him from sacking the city and was subsequently fried by a lightning bolt) and Brunetto Latino, a philosopher Dante viewed as his teacher.[17]

- Eighth Circle: Fraud

- To travel here, Dante and Virgil summon Geryon, a monster that symbolizes the deceptive nature of fraud whose pleasant human face on a monstrous form is akin to an insincere shyster.

- Ring 1: Panderers and seducers — In this ring each sinner is placed in a line to be scourged by horned demons for eternity. They "deliberately exploited the passions of others and so drove them to serve their own interests, are themselves driven and scourged." Most notable here is the hero Jason, who seduced and abandoned Medea in his quest for the Golden Fleece. [18]

- Ring 2: Flatterers — For exploiting others with honeyed words, these sinners get to fight in a pile of shit for eternity.

- Ring 3: Simoniacs — An older way to say indulgences and buying church offices. Dante spends a good bit of time going over how unjust this is, and portrays sinners as head down in a tube of rock akin to a mockery of a baptism font while flames scorch their feet. Dante encounters Pope Nicholas III here, who tells him that future Popes Boniface VIII and Clement V will arrive here as well.

- Ring 4: Sorcerers — Including fortune tellers, diviners, astrologers, and other false prophets that usurp God's prerogative by looking into the future using twisted means. They have their heads turned backwards as many cry about their fate.[19]

- Ring 5: Barrators — Corrupt politicians that make money off their political offices. In Hell they are immersed in a burning lake of pitch guarded by the demon Malacoda and his underlings if they surface.[20] This section of the Canto also relates a several century old fart joke as a demon uses his ass as a trumpet.[21] Dante dwells in this circle for some time, as it was false accusations of graft that led to his exile.

- Ring 6: Hypocrites — Sinners in this ring are forced to walk in circles in leaded and gilded monks' habits representing the fair appearance they maintained among men as well as the terrible weight of their deceit. As they walk, they trample upon the high priest Caiaphas who counseled the Sanhedrin that Jesus had to die for the public good; just as Jesus had to bear the weight of the world's sins, he must now bear the weight of the world's hypocrisy. [22]

- Ring 7: Thieves — These sinners are tortured by climbing over a ruined bridge across a chasm full of monstrous reptiles. If any make it, there are many more bridges according to Dante. The reptiles are in fact sinners themselves, and if they catch one in a human form they commit a very literal form of identity theft as they steal the shape of their victim. [23]

- Ring 8: Counselors of Fraud — People who counseled others to commit fraud who are burned in a continuous flame. Here Dante makes note of Greek heroes that stormed Troy, including Odysseus. He also meets with the political leader Guido da Montefeltro, who had advised Pope Boniface VIII to use a false amnesty to lure a rival political family into a trap and burn down their castle. Boniface had promised him absolution in advance, but as St. Francis was taking him to heaven the devil pointed out the absurdity of being contrite for a sin as one is about to commit it.

- Ring 9: Sowers of Discord — Even complaining can send you to hell where people are hacked and mutilated for all eternity by a large demon wielding a bloody sword. Since sinners are supposedly torn apart as they tried to tear apart God's works in religion, the civil, and family spheres. This ring seems to include any split, as it includes Muhammad, for creating a schism in Christianity, and his son-in-law Ali, for splitting Islam into Shiite and Sunni groups, as well as the knight Bertrand de Born for instigating a quarrel between Henry II of England and his son Henry the Young King.

- Ring 10: Falsifiers — Including alchemists (falsifiers of things), evil impersonators (falsifiers of people), counterfeiters (falsifiers of money), and perjurers (falsifiers of words) that are beset by horrible diseases, stench, thirst, filth, darkness, and screaming.

- Central Well of Malebolge — Before the ninth circle. Classical and biblical giants guard the central well while buried waist deep in the ground with their upper bodies free.[24] All are chained save Antaeus, who did not join the rebellion against the Olympian gods and is not bound (but still buried in the ground). It is very odd how many pagan mythical figures reside in hell.

- Ninth Circle: Treachery — Here Dante sees the frozen lake where those who committed treachery against those they had special relationships with are sent.

- Ring 1: Caïna — Named after Cain as they are traitors to their own kin. They are buried in the ice with just their heads free to bow in order to give some relief from the howling wind in the bottom of the pit.

- Ring 2: Antenora — Named after Antenor, a Trojan who betrayed his city to the Greeks, as they are traitors to their country. They are buried up to their necks without the ability to bow their heads. Here Dante meets Count Ugolino of Pisa, who sought to gain control of Pisa but was himself betrayed by his co-conspirator Archbishop Ruggeri. As he was locked in prison with his sons and grandsons and starved to death alongside them, he is given some small measure of justice by being allowed to gnaw upon Ruggeri, who is frozen beside him.

- Ring 3: Ptolomaea — Named after Ptolemy, who invited his father-in-law Simon Maccabaeus and his sons to a banquet and then killed them, as sinners are traitors to their guests. These sinners are sealed laying down, face up, with their faces free but their tears have frozen to their faces.

- Ring 4: Judecca — Named after Judas as they are traitors to their benefactors. They are sealed completely in the ice in contorted positions.

- Ninth Circle: Treachery — Here Dante sees the frozen lake where those who committed treachery against those they had special relationships with are sent.

- Center of Hell: Condemned for committing the ultimate sin, by his personal treachery against God, the Devil is frozen waist deep in ice, suffering for eternity- the freezing winds here are his wingbeats, which ensure that his own attempts to escape keep him imprisoned. Strangely, he has three faces, one red, one yellow, and one black, often seen as a representation of the perversion of the Trinity of God or his qualities; rather than being omniscient, omnipotent, and benevolent, Satan is powerless, ignorant, and malicious.[25] Judas Iscariot is in one of his three mouths. Brutus and Cassius, who killed Julius Caesar, are in the others.

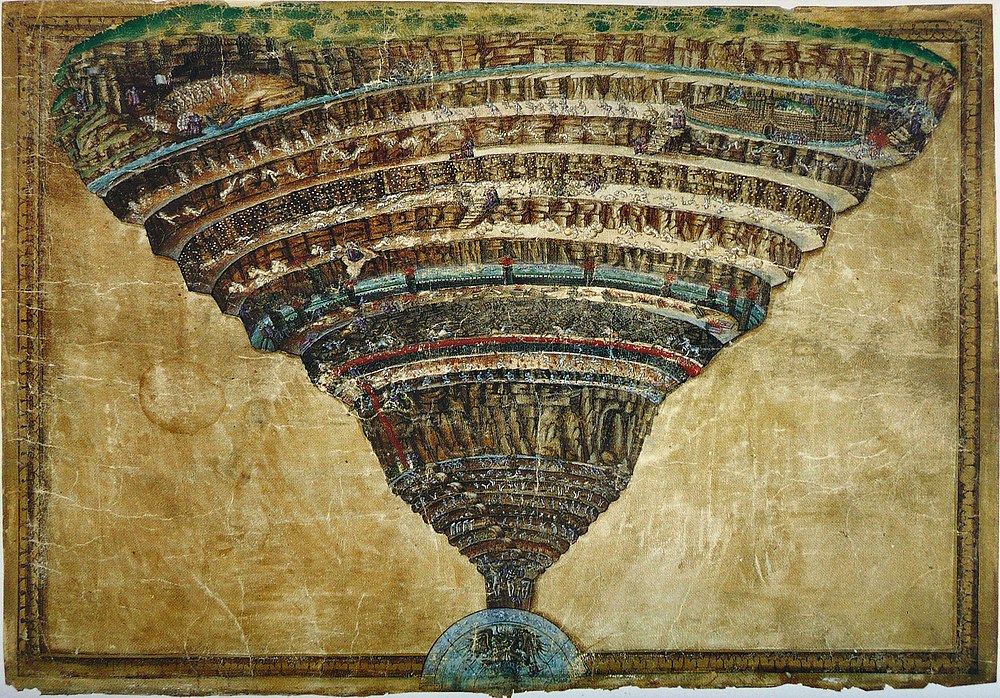

Botticelli's map of Hell[edit]

Italian painter Sandro Botticelli illustrated a copy of Inferno as commissioned by a member of the de'Medici family, and one of the paintings he created was a helpful map of Hell, as seen below.

Purgatory[edit]

Virgil then escorts Dante through purgatory, presented vaguely to be a mountain located somewhere in the Southern hemisphere. There he must pass through the 7 terraces of suffering and spiritual growth. There souls cast off their sins terrace by terrace and assume the virtue that is the opposite.

- Terrace 1: The proud purge their sins and become humble. There souls are forced to carry large stones on their back as they look at beautiful statues of the humble.[26]

- Terrace 2: The envious purge their sins to become generous. The envious are forced to have their eyes sewed shut with iron wire, wear grey cloaks, and listen to voices speak of generosity.

- Terrace 3: The wrathful purge their sins and become meek. There souls are forced to walk in acrid smoke. Dante and Marco Lombardo also have a discussions about free will as they watch the penitent.

- Terrace 4: The slothful purge their sins by becoming ceaselessly active with unbridled zeal.

- Terrace 5: The covetous are forced to lay face down on the ground till they are no longer covetous. It would be hard to find the opposite of wanting too much for a soul that has nothing, cannot acquire anything, and cannot give anything away.

- Terrace 6: The gluttonous are forced to do without or do with temperance. Like Tantalus, some are starved or are given bland food (honey and locusts).

- Terrace 7: The lustful are forced to go through a large wall of flame calling out examples of infidelity and chastity.

According to one passage, no one can be allowed into heaven without passing through the flames on the 7th terrace. In the narrative, Dante himself has to endure them in order to be shown heaven. He says of the experience that he wished to be dipped in molten glass, because it would be cooler than those flames. It is not explained how Dante, who is still alive and in corporeal form, survives the ordeal.

At the end, Dante floats up off the top of Mount Purgatory toward heaven. This is in keeping with the Aristotelian model of matter, which contests that Earth sinks down to the lowest level, and water above that, and air above that, because it is "in their nature" to sort themselves in this manner. The prevailing view was that it was a human's nature to float above even the air, but the "weight of sin" drags us down to stand on the Earth.

Paradise[edit]

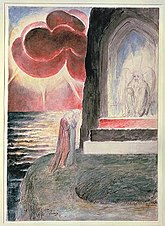

Virgil ends his escort at purgatory, given that he has not earned the right to visit heaven as he was a pagan. There Dante is met by Beatrice Portinari![]() , a Florentine woman whom Dante is thought to have been in love with but who married another suitor and died 18 years before the start of this poem. Beatrice guides Dante through the spheres of heaven, represented by the "planets" that were known at the time. (The spheres are arranged in the same order as Aristotle's spheres of crystalline aether.)

, a Florentine woman whom Dante is thought to have been in love with but who married another suitor and died 18 years before the start of this poem. Beatrice guides Dante through the spheres of heaven, represented by the "planets" that were known at the time. (The spheres are arranged in the same order as Aristotle's spheres of crystalline aether.)

- Sphere 1 — The Moon: The Inconstant — It is associated with souls of those who were deficient in the virtue of fortitude but strong to their vows.[27] Also representing optics and the scientific method.

- Sphere 2 — Mercury: The Ambitious — Here is the representation of those who wished to do good out of desire for fame but lacked the virtue of justice. Dante meets the Byzantine Emperor Justinian here.

- Sphere 3 — Venus: The Lovers — Residing here are those lovers who didn't practice the virtue of temperance.

- Sphere 4 — The Sun: The Wise — Here Dante meets the examples of prudence- the souls of the wise that helped to illuminate the world intellectually. Among their number are Thomas Aquinas and King Solomon. [28]

- Sphere 5 — Mars: The Warriors of the Faith — This is the home of the warriors of the Faith that gave their lives for God, displaying the virtue of fortitude. Dante sees Charlemagne and his heroic nephew Roland there, along with his great-great-grandfather, the Crusader Cacciaguida degli Elisei.

- Sphere 6 — Jupiter: The Just Rulers — Home of the rulers who were just, which surprisingly includes the (pagan) Emperor Trajan- a legend at the time claimed he was resurrected just long enough to become a Christian and was subsequently allowed into heaven. It is one of the few easy to decipher allegories.

- Sphere 7 — Saturn: The Contemplatives — Home of the virtues of temperance, associated with monks and theology.

- Sphere 8 — The Fixed Stars: Faith, Hope, and Love — Representing the church triumphant. Dante meets with the saints Peter, James, and John; St. Peter strongly denounces the corruption of the Catholic Church that claims to act as his successor. Adam also appears here, and clarifies that his sin was not eating of the forbidden fruit so much as his transgression of God's command in doing so.

- Sphere 9 — The Primum Mobile: The Angels — The abode of angels who Dante attributes to moving all of the other spheres. Here Beatrice describes the creation of angels and the universe, as well as criticizing contemporary preachers of Dante's time.

- The Empyrean: The House of God and enthroned souls of the faithful where angels fly distributing peace and love. There St. Bernard describes predestination to Dante as a divine knowledge of what will pass instead of removal of free will. An idea in the 12th-13th centuries proposed by Thomas Aquinas and William of Ockham. The final scene is Dante gaining a glimpse of the face of God, which takes the form of three circles of the same size all occupying one space (as the Trinity) with the human form of Jesus contained within them. Though he finds he cannot express it in words, he comes to an understanding of how the members of the Trinity fit together along with the relation between the humanity of Jesus and the divinity of the Son, and feels himself truly united with God's love.

Scientific themes[edit]

The importance of the scientific method[edit]

Dante discusses the importance of the scientific method in the Paradiso. Consider the following example in lines 94–105 of Canto II:

“” Yet an experiment, were you to try it,

could free you from your cavil and the source of your arts' course springs from experiment. Taking three mirrors, place a pair of them at equal distance from you; set the third midway between those two, but farther back. Then, turning toward them, at your back have placed a light that kindles those three mirrors and returns to you, reflected by them all. Although the image in the farthest glass will be of lesser size, there you will see that it must match the brightness of the rest.[29] |

Spherical Earth[edit]

The Purgatorio speaks about a spherical Earth and the implications of this, such as the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the Sun, and the various timezones of the Earth. For example, at sunset in Purgatory it is midnight at the Ebro, dawn in Jerusalem, and noon on the River Ganges. Consider the following example from Canto XXVII of the Purgatorio.

“”Just as, there where its Maker shed His blood,

the sun shed its first rays, and Ebro lay beneath high Libra, and the ninth hour's rays were scorching Ganges' waves; so here, the sun stood at the point of day's departure when God's angel—happy—showed himself to us.[30] |

Dante travels through the centre of the Earth in the Inferno, and comments on the resulting change in the direction of gravity in Canto XXXIV (lines 76–120). A little earlier (XXXIII, 102–105), he queries the existence of wind in the frozen inner circle of hell, since it has no temperature differentials.[31]

See also[edit]

- Dan Brown, whose Inferno is kind of a love letter to Dante.

External links[edit]

- The Divine Comedy in Italian and English on Wikisource

- "Which circle of Dante's Inferno will you go to?" test

References[edit]

- ↑ Michael Caesar, Dante: The Critical Heritage, Routledge, 1995, pp. 288, 383, 412, 631.

- ↑ "Epistle to Can Grande". faculty.georgetown.edu. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto XIX.

- ↑ John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto III, pg. 36

- ↑ Gagarin, Michael. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, Volume 7. p. 359.

- ↑ Psalm 89:10, Vulgate; Psalm 90:10, KJV

- ↑ John Ciardi, Inferno, notes on Canto XI, pg. 94

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, Hell, notes on Canto IV

- ↑ Inferno, Canto IV, line 36

- ↑ Inferno, Canto IV, line 151

- ↑ Inferno, Canto V, line 38

- ↑ Inferno, Canto VI, pg. 54

- ↑ Inferno, Canto VII, line 47,

- ↑ Canto VII

- ↑ Inferno Canto X, line 15

- ↑ Inferno, Canto XII

- ↑ Inferno, Canto XIV

- ↑ Inferno, Canto XVIII

- ↑ Inferno, Canto XX, lines 28-30

- ↑ Canto XXI, lines 112-114

- ↑ Patterson, Victoria. "Great Farts in Literature". The Nervous Breakdown

- ↑ Inferno, Canto XXIII

- ↑ Inferno, Canto XXIV

- ↑ Inferno, Canto XXXII.

- ↑ Inferno, Canto XXXIV

- ↑ Purgatorio, Canto XI

- ↑ Paradiso, Canto II

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, Paradise, notes on Canto X.

- ↑ Paradiso, Canto II, lines 94–105, Mandelbaum translation.

- ↑ Purgatorio, Canto XXVII, lines 1–6, Mandelbaum translation.

- ↑ Dorothy L. Sayers, Inferno, notes on p. 284.